After plenty of heated discussion, one half of the alleged Boston bombing pair was buried in a Muslim cemetery in VA last week. The discussion that preceded that burial all centered on the visceral opposition all the local cemeteries displayed toward even the suggestion of burying him. Family and friends of those interred in various cemeteries across New England considered it an affront to the memory of their late loved ones for an alleged terrorist to be buried alongside them. In a deeply classy move, one Yale Divinity School alum offered his burial plot in a cemetery just outside of New Haven, CT. On my bike commute into school each day, I pass that cemetery, and the thought of having Tsarnaev buried there (though he finally was not) was the cause for plenty of reflection upon the justice of burying him at all. And I have decided, with all due respect to those families who opposed his burial, that not only is burial a most Christian and civilized thing to do, it is also the most grave.

Opposition to burying him seemed to center around the idea that burial was somehow an honorific status, that burial was ‘too good’ for him and that for him, ostensibly, the far more desirable thing would be to fling his body into a junkyard or into a cave, or something of the like. Such ideas are understandable, and they are not without precedent, but that precedent is unequivocally non-Christian. It is a pagan principle. In the Greek and Roman epics, the right of passage into Hades is a proper burial of the corpse. Thus King Priam steals away by night to the implacable Achilles and, setting aside his kingly honor, begs for the body of his beloved son Hector so that he might be properly buried. Though his fall of his Trojan kingdom is visible on the horizon, Priam knows that Hector must be buried, otherwise he is doomed to wander about on the outskirts of Hades, unable to pay the boatman to ferry him across the river to the place of rest among the rest of the gallant heroes.

But Christianity has no such image. So why, then, do we bury? In Christianity, burial is not merely an efficient means of disposing of or forgetting a body when its soul has departed. It is a symbol. Returning again to our Greek epics, there we see that the bodies of deceased heroes are burned upon ceremonial pyres as the highest posthumous honor possible and the prerequisite for entry into the Underworld. But in Christianity the image is quite different. The body is placed intact into a box which is then placed into the ground, and the location is marked. This all bears the markings of what we do with time capsules, and indeed the meaning is the same. All Christians who bury their dead understand this: their bodies will not stay there forever. Indeed, the dead shall be inexorably summoned from their graves, and what awaits them after that summons is a judgment.

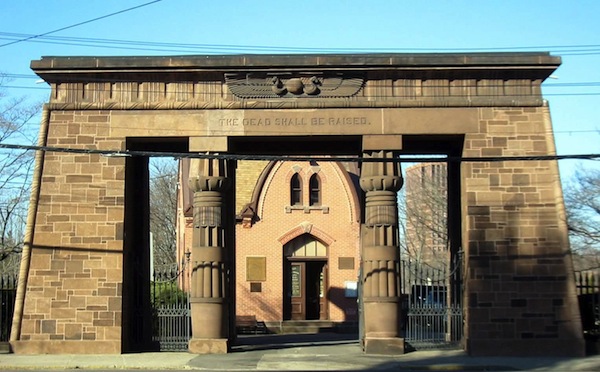

At the center of Yale University’s campus is the Grove Street Cemetery, and above the entrance to that cemetery stands a monumental gate engraved with the words: “THE DEAD SHALL BE RAISED.” It stands over my great and prestigious university as an untiring herald of the harrowing news that one day our academic task will cease, the laboratories will go dim, the libraries turn empty. Our books of study will be closed and God’s book of judgment will be opened. In the Christian mind, such a reminder is both a consolation and a warning. It’s a consolation because the righteous deceased interred there shall rise again and be vindicated. It’s a warning because the vicious interred there shall face a strict judgment from which we living are not ultimately spared. Death will not have final word over the faithful deceased, whose lives evidenced acts of love and whose faith was in Christ alone for the forgiveness of their sins. Nor is death the final word for the vicious departed whose lives bore little concern for others and whose faith was in all but Christ. Both shall be judged but a perfectly just judge whose verdicts cannot be swayed and whose arm is not shortened in judgment. Therefore the very act of burial is a hint of the future judgment. To inter a body is to place its name upon the divine docket for judgment. By placing Tsarnaev into the ground, we remind ourselves that he is not beyond the justice of the Divine. Yet nor are we. The life lived with that keen awareness is a life well-lived.