MAGIC is everywhere you look these days. From bookstores to movie theatres, stories about wizards, witches and mythological beasts are all the rage; and for a person like me, who grew up with hobbits, aliens, flying horses and Jedi Knights, the current fantasy craze — and the various Christian responses to it — bring back a lot of memories.

MAGIC is everywhere you look these days. From bookstores to movie theatres, stories about wizards, witches and mythological beasts are all the rage; and for a person like me, who grew up with hobbits, aliens, flying horses and Jedi Knights, the current fantasy craze — and the various Christian responses to it — bring back a lot of memories.

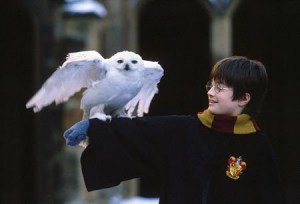

How popular is fantasy right now? The most successful movie of the year (so far) is Shrek, a cheeky parody of the fairy tale genre that turns conventional wisdom about ogres, dragons and beautiful princesses on its head. That film’s box office performance could be surpassed in a few weeks by Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, the first film based on J.K. Rowling’s phenomenally popular novels about a young orphan and his classmates at Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry.

Meanwhile, fans of J.R.R. Tolkien’s epic fantasy The Lord of the Rings eagerly await the December 19 release of The Fellowship of the Ring, Peter Jackson’s adaptation of the first book in Tolkien’s famous trilogy.

And there’s no end to the make-believe in sight — sequels to all these films are in the works, and George Lucas is already releasing trailers for Attack of the Clones, the next installment in his Star Wars series.

How should Christians respond to this flood of stories, all of which involve the supernatural in some form? Some would prefer to dismiss them altogether. A woman I once knew was offended when our church showed a cartoon based on The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, the first book in C.S. Lewis’s Narnia Chronicles; any story about witches was simply unfit for public consumption, in her view, even if the witch was clearly depicted as an enemy of Christ.

Others are more cautious; although they may believe fantasy is dangerous, they make an exception for stories by certifiably Christian authors such as Tolkien and Lewis. As Cornerstone editor Mike Hertenstein has put it, people who adopt this view are motivated not by critical thinking, but by “family pride” — these books are ours and those books are theirs. For these critics, learning how to discern truth within any given story is not as important as determining which stories are ‘safe’.

A typical example of this approach can be found in Richard Abanes’ book Harry Potter and the Bible: The Menace Behind the Magick. First, he compiles a thorough list of complaints that have been thrown at the Potter books — the children occasionally use mild profanities like “damn,” the centaurs practice a form of astrology, the books blur the line between reality and fantasy and so on. Then, he goes on to promote the writings of Lewis and Tolkien, apparently oblivious to the fact that many of his criticisms could be applied to their stories, too.

Sometimes Abanes’ reasons for rejecting one set of stories and not the other get excessively technical: Gandalf, the wizard in Tolkien’s stories, is okay, because he is not really a human wizard, but a sort of angelic creature to whom supernatural powers come quite naturally; Harry Potter, on the other hand, is not okay, because he’s just a human boy who is messing with things that human boys shouldn’t be messing with.

But in making this argument, Abanes misses the point, on two counts. First, it is clear in Rowling’s stories that her wizards and witches are born with their abilities, and thus, magic is as natural to them as it is to Gandalf; in this, Harry Potter and his friends are similar to the mutant superheroes in X-Men, who acquire their powers when they hit puberty. But more importantly, the approach espoused by Abanes is terribly literalistic, and thus rather superficial; readers who approach stories this way are like the crowds in Monty Python’s Life of Brian, who never quite ‘get’ the parables they hear because they keep picking away at the details.

To the average reader, it probably makes not one bit of difference whether Harry Potter or the X-Men get their powers through witchcraft or genetic mutations; these stories appeal to us because they speak to our need for family and community, as well as our need to accept those things about us that make us feel freakish or different from other people. Similarly, when Frodo Baggins struggles with the temptation to wear the One Ring, or when Luke Skywalker fights the impulse to give in to the Dark Side of the Force, we identify with their need to resist evil; whatever imaginary theology lies behind their stories is of lesser importance.

In her more balanced assessment of the Potter phenomenon, What’s a Christian to Do with Harry Potter?, Connie Neal explains how young children need stories to cope with their increasing awareness that they are vulnerable and living in a world that is full of dangers. Stories about people who defy gravity and make food appear out of thin air provide children with a temporary form of imaginary control, but they can also inspire children to face the world with the same sort of courage that the heroes show.

Stories can also help us to cope with the problems in our lives by allowing us to reflect on them in a fictionalized form. As Carolyn Whitney-Brown, who leads courses and workshops on Harry Potter in Toronto, has said, children who are coping with pain and bereavement often can’t talk about their own suffering — but they can talk about Harry’s.

Instead of treating stories as boundary markers, we need to engage with stories and recognize that they are often more complex than some of the more ideological critics give them credit for. The best of them can often be interpreted in different, even contradictory, ways. Take the ending of Shrek — and if you haven’t seen the film yet, you may want to skip ahead a few paragraphs — and the moment in which the princess falls in love with the titular ogre and becomes an ogre herself.

In a surprisingly hostile review for Books & Culture (published by Christianity Today), Eric Metaxas said the film scorned beauty and glorified ugliness. Others, however, appreciated the way the film challenged the glorification of physical beauty and encouraged us to focus on inner beauty instead. A third group acknowledged the film’s intended message, yet criticized it all the same, because to them, the film seemed to condone a form of segregation; a more progressive film, they said, would have allowed a ‘beautiful’ human and an ‘ugly’ ogre to pair off despite their differences. All of these interpretations are valid, to a point, and it is by sharing stories like Shrek that people with different points of view can try to find a common language and communicate their beliefs.

C.S. Lewis liked to say that the Christian story is a true myth — it is grounded in the historical reality of the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus, but it plays on our imaginations in the same way that other myths do. And sometimes those other myths can play a part in opening our minds to the sense of ‘joy’ that Lewis believed was essential to our faith. Indeed, it was Lewis’s love of myths and fairy tales — some pagan, some not — that awakened him to his own need for ‘joy’, which was ultimately fulfilled in Christ.

In his book Reel Spirituality: Theology and Film in Dialogue, Robert K. Johnston, professor of theology and culture at Fuller Theological Seminary, points out that Christian theology is, at heart, a story in and of itself. And like all stories, it has the power to produce a sense of awe and transform our lives. As Johnston says, it’s important to pay close attention to the stories our culture tells, including fantasies — not only so that we can learn how to better share the gospel, but so that we can hear what God is trying to say to us through the films themselves.

— A version of this article was first published in BC Christian News.