In my study of Acts for my upcoming revision and expansion of The Untold Story of the New Testament Church (which will be retitled), I was eager to get my hands on J.B. Lightfoot’s commentary on Acts.

The commentary is beautifully put together, and Lightfoot’s material on the travels mentioned in Acts is worth the price of admission. Greater still, Lightfoot’s ability to weave Greek texts in shedding light on the book of Acts is both exciting and illuminating. I’ll make great use of this book for my research in my forthcoming book.

Here’s a more extensive review by Phillip J. Long.

Lightfoot, J. B. The Acts of the Apostles: A Newly Discovered Commentary. Edited by Ben Witherington III and Todd D. Still. The Lightfoot Legacy Set 1; Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity, 2014. 399 pp. Hb; $40.00. Link to IVP

Ben Witherington discovered the hand-written manuscript of this long-forgotten commentary on Acts by J. B. Lightfoot in the spring of 2013. The introduction to the commentary explains how Witherington had an opportunity to examine Lightfoot’s papers during a sabbatical visit at St. John’s College at Durham University. (See also Witherington’s “Text Archaeology: The Finding of Lightfoot’s Lost Manuscripts,” Biblical Archaeology Review 40.2 [March/April 2014]).

This volume contains 6 black and white glossy pages of photographs illustrating the original pages discovered at Durham. According to IVP Academic, there are two more volumes planned in this series, one on the Gospel of John and another on 2 Corinthians and 1 Peter.

Why would anyone care to read a lost commentary written by a scholar who died in 1889? For some modern readers, Lightfoot’s legacy has been forgotten. But the mid-nineteen century, Lightfoot was considered one of the foremost scholars of his day. The editors of this book begin their introduction with the words of William Sanday: “No one could match Lightfoot for ‘exactness of scholarship, with the erudition, scientific method, sobriety of judgment and lucidity of style.’” His commentaries on the Galatians (1865), Philippians (1868) and Colossians (1875) are often reprinted and his work on the Apostolic Fathers was the standard until the Loeb edition by Krisopp Lake.

Witherington says “Lightfoot believed wholeheartedly that nothing could be theologically true that was historically false when it comes to matters involving a historical religion such as Christianity” (36). Lightfoot believed that “Faith seeking understanding” and “honesty about early Christianity and its Lord need not be feared by a person of Christian faith” (40).

The authors of the introduction to the commentary are obviously infatuated with Lightfoot and sometimes bemoan the fact that this material was not published soon after was written. If it had been, Witherington speculates, perhaps it would have “forestalled all sorts of rash judgments about Luke as a writer of Greek orHe historian and would equally have made it impossible the conjecture that this document was written in the second century A.D. (39).

Lightfoot offers a discussion of the inspiration of Scripture as a “pre-introduction” to his commentary. Lightfoot balances divine inspiration with human agency in a way that seems familiar to evangelicals today. He calls inspiration which loses sight of human agency “irrational.”

“The timidity which shrinks from the application of modern science or criticism to the interpretation of Scripture, is evinces a very unworthy view of its character. If the Scriptures are indeed true, they must be in accordance with every true principle of whatever kind” (49). This tenacious commitment to both Scripture and Reason is rare in the modern commentator, favoring either one or the other extreme.

With respect to typical matters of introduction, Lightfoot begins with a discussion of the manuscripts he will use in his commentary. After briefly discussing the rules of textual criticism, he offers a short history of textual criticism in modern times. Remember Tischendorf had only just discovered and published Sinaticus when this commentary was being written. Alexandrinus and Vaticanus are the two main texts he consults, along with Codex C and Codex Bezae.

He offers several pages on the authenticity and credibility of the book of Acts. This section appears in more or less outline format and some of his points are not argued. Obviously if this commentary were completed these points would have been expanded. With respect to authorship, Lightfoot believes it is undoubted the author was a companion of Paul, and concludes the traditional view Luke is the author seems to be “the most natural conclusion” (65).

The commentary itself proceeds as does Lightfoot’s other commentaries. He begins with a brief summary of the pericope followed by short notes on Greek words and phrases of interest. After this commentary, there are a few pages of notes on the Greek text itself, commenting on textual variants and suggesting solutions.

The editors the book describe Lightfoot as a “walking lexicon of Greek literature of all sorts, and not infrequently he was able to cite definitive parallels to New Testament usage that decided the issue of the meaning of a word or a phrase” (38). This is clear from a reading of the commentary; Lightfoot constantly cites a wide range of classical Greek sources to illustrate the meaning of the text.

With respect to textual critical issues Lightfoot touches on a large number of variants, often arguing the Received Text (the Majority Text) is in error and must be modified. Lightfoot obviously wrote well before the discovery of most of the papyri and he certainly is unaware of the vast majority of manuscripts which have come to light since the middle of the 19th century. Nevertheless his comments on textual criticism are often insightful for understanding the text of Acts.

The editors of the commentary provide occasional footnotes reporting corrections of marginal comments made by Lightfoot at a later time. For example, occasionally the editors include penciled in comments like “this was written before I saw Alford’s note” (p. 199). Sometimes the editors correct Lightfoot where he has cited the wrong text (p. 103).

Appendices. Following the commentary, the editors have included several additional items related to Lightfoot’s work on Acts. First, an article on Acts for Smith’s Dictionary of the Bible is included (279-326). The editors speculate this introduction was one of the last pieces he ever wrote on the New Testament. It is in fact a worthy introduction to a commentary on Acts.

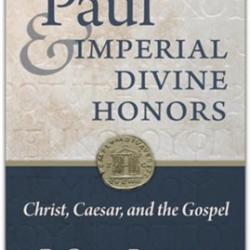

The second appendix is an article entitled “Illustrations on the Acts from Recent Discoveries,” originally published in Contemporary Review in May 1878 (327-337). Lightfoot states “no ancient work affords so many tests of veracity,” a remarkable statement compared to contemporary commentaries on Acts which dismiss the book as historically unreliable. I doubt this brief article would convince anyone today dismiss the historical value of the Book of Acts.

A third appendix reprints a lecture on Paul’s history after Acts. Lightfoot surveys a number of early church writers who report the tradition Paul was released after the book of acts and continued his ministry in Spain. He therefore assumes this widely excepted tradition in sketches a brief chronology of what happened after Paul was released from prison. Order to do this Lightfoot makes use of the Pastoral Epistles, another rare practice in contemporary commentaries on the Book of Acts.

The final appendix is Lightfoot’s obituary from Contemporary Review in published in 1893 (352-386). The editors have enhanced this piece by adding footnotes identifying the various works mentioned in this anonymous homage, likely penned by either John Harmer or F. J. A. Hort, according to Witherington.

Conclusion. Overall this commentary is a valuable contribution to the history of scholarship on the Book of Acts. Modern commentaries still cite Lightfoot and his views on textual issues and lexical issues should not be taken lightly. Yet it must be understood this commentary is 150 years old and Lightfoot is simply unaware of the research done on the Second Temple Period in recent years. Nevertheless the simplicity and clarity of Lightfoot’s commentary is a joy to read. Like the Ancient Christian Commentaries and the Reformation Commentary published by IVP Academic, this commentary serves the purpose for which it was intended. This is not a cutting-edge, highly detailed commentary on Acts, but it does reflect serious exegesis from one of the great commentators of the nineteenth century.

by Phillip J. Long, Source.

Here’s a note from the publisher about the book

InterVarsity Press is proud to present The Lightfoot Legacy, a three-volume set of previously unpublished material from J. B. Lightfoot, one of the great biblical scholars of the modern era. In the spring of 2013, Ben Witherington III discovered hundreds of pages of biblical commentary by Lightfoot in the Durham Cathedral Library. While incomplete, these commentaries represent a goldmine for historians and biblical scholars, as well as for the many people who have found Lightfoot’s work both informative and edifying, deeply learned and pastorally sensitive.

Among those many pages were two sets of lecture notes on the Acts of the Apostles. Together they amount to a richly detailed, albeit unfinished, commentary on Acts 1-21. The project of writing a commentary on Acts had long been on Lightfoot’s mind, and in the 1880s he wrote an article about the book for the second British edition of William Smith’s Dictionary of the Bible. Thankfully, that is not all he left behind.

Now on display for all to see, these commentary notes reveal a scholar well ahead of his time, one of the great minds of his or any generation. Well over a century later, The Acts of the Apostles remains a relevant and significant resource for the church today.