Back in 1934, the pioneering sociologist Thorsten Veblen published The Theory of the Leisure Class, which gave us the term “conspicuous consumption,” the notion that people proclaim their wealth and thus their social status to the world by means of the luxury products they buy and show off. (For example, Porsches, Gucci, and Rolex.) Furthermore, people who aren’t all that wealthy but who want to be perceived as having a higher social status are often even more obsessed with conspicuous consumption, as in the ever-changing must-have brands of teenage fashion.)

Veblen also wrote about “conspicuous leisure,” by which people advertise their social status by displaying their luxurious hobbies and vacations. (Again, not-so-wealthy people play the same game. Just read people’s T-shirts.)

To that list of status accessories we can now add “luxury beliefs.” That term comes from Rob Henderson, whose bestselling book Troubled: A Memoir of Foster Care, Family, and Social Class tells of his growing up in poverty and a highly dysfunctional family, how the military helped him get his act together, and how he got accepted into Yale, ushering him into a completely different social scene.

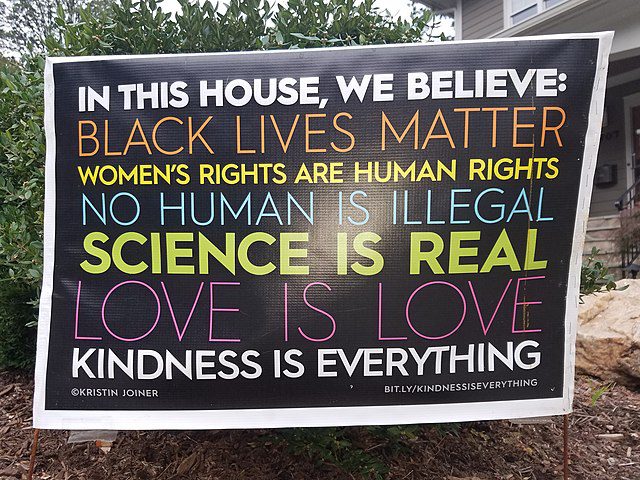

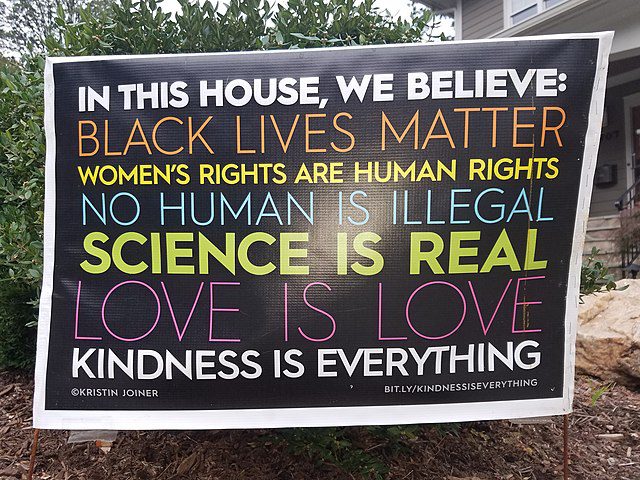

Henderson says that today, people signal their social status and the elites recognize who truly belongs by means of “luxury beliefs.” (See my post on his concept from a few years ago.) Part of his cognitive dissonance was that his new elite friends held to ideas that they themselves did not put into practice, beliefs whose consequences he did experience firsthand in his lower-class misery. Samuel Negus explains in a review of Henderson’s book (my bolds):

Henderson has coined the term “luxury beliefs” for the nexus of elite opinions he encountered at these institutions. The concept is transposed from sociologist Thorstein Veblen’s theory that elite classes advertise their status by conspicuous displays of luxury goods. Henderson found that his instructors and fellow students professed adherence to many destructively contradictory ideas. Either his peers did not follow these professions in practice, or, if they did, the consequences fell principally on those of a lower class. Examples included drug legalization, defunding the police, and eschewing marriage. In Henderson’s impoverished, high-crime, drug-ravaged community, all his friends’ parents were divorced (if they had ever married at all). His Yale classmates came from intact households in expensive, low-crime zip codes. As he pointedly notes, “Graduate students at top universities say ‘marriage is just a piece of paper’ [but] I never heard them ridicule a college degree” in the same terms.

Holding high-minded ideals, though, is a status symbol, with the elite seemingly oblivious to the consequences. “Henderson’s comments on race-conscious admissions are particularly poignant,” says Negus:

Elite colleges’ commitment to “diversity” in their student bodies represents what Henderson terms “trickle-down meritocracy.” Selective institutions “strip-mine talented people,” assuming that “somehow the advantages they accrue will” benefit their old neighborhoods. Instead, most “relocate to a handful of cities where they live alongside their highly educated peers, eroding their bonds of solidarity with those they left behind.”

Now connect this elite class consciousness to the book White Rural Rage that we blogged about and to the way the Democratic party has abandoned its working class roots for upper class progress.

This isn’t to say that the progressive beliefs of this social class and those who aspire to it are not sincerely held. It’s just that there is considerable peer pressure to hold to them. See, for example, yesterday’s post about women who are privately conservative often hiding their convictions for social reasons.

I admit that this can go the other way also. There is peer pressure in the working class to be politically conservative, though such beliefs might interfere with upward mobility. And, of course, there are some conservatives by conviction in the upper crust, just as there are still some leftists among the proletariat. (Notice the irony of that sentence and the role reversal of the social classes since Marxism came apart.) The point is, our beliefs have a social component, which is one of the many reasons why Christians need the community of the church.

Photo by Steve.fami.ly – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=95583843