I wanted to title our new book “Metachurch.” Get it? Not “megachurch” but “metachurch,” one that uniquely addresses the postmodern mind. CPH, no doubt correctly, thought that was too weird. We finally settled on Authentic Christianity: How Lutheran Theology Speaks to the Postmodern World. But the “meta-” quality of Lutheranism remains a theme of the book.

The prefix, from the Greek preposition meaning “beyond” among other meanings, has come to be used for overarching or self-referential meanings.

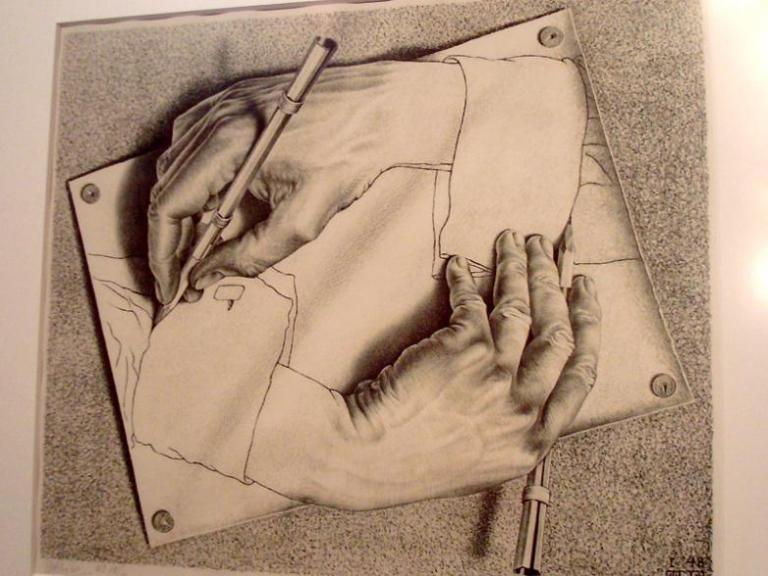

Postmodernist literature, films, and art are full of “meta-” elements in the sense of a work referring to itself. A story about an author who writes a story, which turns out to be the story we are reading–that’s “meta-.” Seinfeld was considered a postmodern situation comedy, as when it showed a comedian named Jerry Seinfeld pitching an idea for a situation comedy to NBC, which featured George, Elaine, and Kramer and was the very series we were watching. “Meta-” here is short for the postmodernist device of “metafiction”; that is, fiction about fiction.

“Metadata” is data about data. “Metalanguage” is language about language. A “metanarrative” is a narrative that includes all narratives.

The first one to formulate this device? Our friend J. G. Hamann is considered the first to use the term in this philosophical sense (at least in German). (Not counting Aristotle, who coined the word and the discipline of metaphysics, but this is in a different sense.)

So how do Lutherans constitute a “metachurch”? How is Lutheranism a sort of “metatheology”?

There are two major strains of Christianity: one is sacramental (Catholicism, Orthodoxy) and the other can be described as evangelical (most Protestant traditions). Lutheranism embraces them both. Anglicanism offers a via media drawing on elements of both. But Lutheranism is very sacramental and very evangelical.

Lutherans preach the Gospel and hold to the Bible as much as any Baptist. They also hold to Baptismal regeneration and the real presence of Christ in Holy Communion as much as any Catholic. Lutherans emphasize preaching and they also worship liturgically.

Even within Protestantism, Lutheranism offers a way to hold on to two seemingly conflicting strains of theology. Lutherans are like the Reformed in being monergistic, in emphasizing the solas, that God accomplishes everything for our salvation. But they are like Arminians in insisting that Christ died for all, that potentially anyone may be saved.

Charismatics emphasize God’s gifts, which they understand in terms of the Holy Spirit granting supernatural experiences. Lutherans too emphasize God’s gifts and supernatural experiences, though they understand these to come not from inside the believer, but from outside of the believer. Lutherans see the Sacraments as God’s gifts, including the Word, in which the Holy Spirit comes to us. Receiving Christ’s Body and Blood, hearing His Word of forgiveness in absolution, hearing and reading God’s Word–these are supernatural experiences, though they are hidden in ordinary bread, wine, pastors, and ink on paper.

So Lutheranism offers a theology of theologies, a church of churches. This “meta-” quality means that Lutherans can draw on insights from Christian churches in all of their diversity.

This also means that Lutheranism is criticized from all sides. Catholics condemn Lutheranism as the source of all Protestantisms. Most other Protestants criticize Lutheranism for being “too Catholic.” The Reformed think Lutherans are too Arminian, and Arminians think Lutherans are too Reformed.

Conversely, Lutherans are always fighting on all fronts, having to critique Catholics, Reformed, Arminians, Charismatics, etc.

As we argue in our book, Lutheranism offers not just one theology among many to choose from. Postmodernists are confused by the diversity of Christian traditions and use this as an excuse for relativism. Lutheranism offers a different way of account for Christian diversity, by showing what is true (as well as false) in them all and by offering a bigger theological framework that encompasses them all.

Our postmodernist world, we argue, need not just a theology but a metatheology. Not a megachurch but a metachurch.

(I see that some church growthers are using the term for congregations consisting of small groups. That’s not the postmodernist sense at all, and I’m not sure what is “meta-” about that structure. The meaning we are proposing here is more like the opposite, not small groups going their own way, but a conceptual framework for bringing diverse fragments together into a whole. But that other people are using the term in a very different sense shows the wisdom of CPH in not letting us use a confusing title.)

Illustration by a_marga, “Las manos de Escher” [the hands of Escher, an example of self-referential, “meta-,” art about art], via Flickr, Creative Commons License. Based on a work by M. C. Escher.