I’m in a reading group with a bunch of pastors, which has me reading titles I would probably miss on my own. I just finished a remarkable book from the 19th century that explains, in practical detail, how to be a pastor. That is to say, it gives advice to young pastors about how to navigate successfully the issues they will face in their ministry.

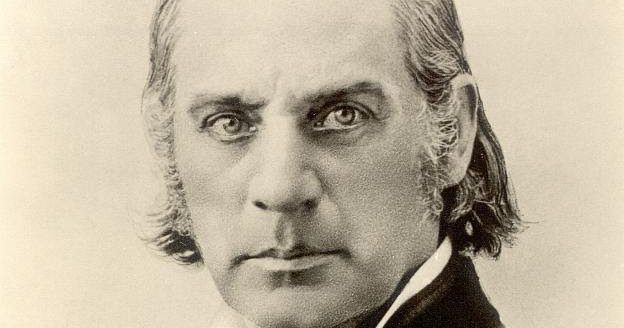

The author is Wilhelm Loehe, and the book is The Pastor, published by CPH in 2015, a translation of two booklets that Loehe wrote in 1847 and 1853. Loehe (1808-1872) was an important figure in the confessional revival in Germany. He is notable for his work in sending missionaries, including to North America, where the pastors he sent over became instrumental in founding the Lutheran Church Missouri-Synod. He was a key figure in the deaconness movement and was a founder of the institution that would become Concordia Theological Seminary in Ft. Wayne, Indiana.

Today Loehe’s theology, with his emphasis on liturgy and the sacraments, is especially appreciated by “high church” Lutherans. Some of his teachings, such as the notion that the ministry comes straight from Christ rather than through the call of a congregation, would go against LCMS teachings, but these, when they turn up are duly treated in footnotes. But they seldom do. This book focuses less on theology and more on the practice of being an effective pastor. As such, even non-Lutheran pastors would find this treatment illuminating.

Loehe is addressing in particular new pastors just starting out in rural parishes. He stresses the importance of “belonging to all your parishioners.”

Certainly times and culture have changed. But his advice is startlingly relevant to what pastors face today. For example, in his discussion of pastoral education, he cites the importance of a liberal arts, university education. With such an education, “he will be equal to all levels of society and can claim admittance to even the highest circles” (p.5). Now Loehe goes on to warn against over-intellectualizing ministerial training, recommending that practical pastoral training precede the technical scholarly study of theology. But he is right that pastors, perhaps more than members of any other profession, must be able to work with individuals from all levels of society and cultural backgrounds. In his day, a country pastor had to deal with the nobility in the manor house, as well as the peasants in the field, as well as all of the craftsmen, merchants, and professionals in between.

Today our congregations are probably much more culturally homogenous. The church growth theory pioneered by Donald McGavran teaches that churches grow best when they consist of people from the same socio-economic-cultural background, so that most large congregations today are made up of middle class suburbanites. But rural and small town congregations are still typically made up of people from all walks of life, and even larger congregations are now having to deal with diversity, not just that of race, but of cultural and individual backgrounds. Pastors today will typically need to interact with well-educated professionals, blue-collar workers, millennials, teen-agers, immigrants, scientists, retired folks, farmers, etc., etc. Doing so will require wide-ranging knowledge, humility, and cultural savvy.

I did not expect a 19th century writer to be so attuned to social and cultural dynamics. Loehe gives good advice to young pastors on starting out in their office–creating the right impressions, balancing friendliness and reserve; socializing with brother pastors and with parishioners; dealing with the legacy (good and bad) of predecessors; and navigating what we would call church politics.

Loehe discusses how pastors should handle finances, deal with the school when there is one, and balance hobbies with his ministry. He also gives wise counsel on how to help the poor and how to minister appropriately to women.

To be sure, there are big differences between his time and today, and the vivid portrait of 19th century rural parishes is part of the charm of this book. He writes about receiving the “collection”–the members bringing eggs, vegetables, and other produce as part of the pastor’s pay; renting out or managing the land that would sometimes be attached to the parish for the pastor’s support; managing servants. (We learn that pastors usually get good servants because “parents love to place their children [for service] in parsonages,” due to their good moral influence [p. 113]).

Loehe includes a chapter on marriage, treating whether to choose marriage or celibacy; qualities to look for in a bride; the role of the pastor’s wife; raising children in the parish. This is clearly highly Victorian–such as his euphemistic references to “the marital secret” and his simultaneous idealization and subordination of women–but there is also much good sense and wisdom along the way.

Loehe directs much of his advice to young pastors, but he covers the whole course of a pastor’s life, including how to handle old age and retirement (and knowing when it is time to step aside).

The first booklet has to do with the personal and practical issues that a pastor will need to deal with. The second booklet focuses on what the pastor does: homiletics, catechesis, liturgics, pastoral care, and pastoral care of the sick.

In the section on homiletics, Loehe discusses types and methods of teaching, rhetorical techniques, types of sermons, studying and preaching from Scripture; extemporaneous speaking vs. writing out the sermon; style; and the proper and improper use of sermon books. (We would say online sermons.) Throughout, he gives advice that grows out of extensive experience. Don’t preach sermons that are too long, he says, since that could put the divine service as a whole out of balance. The best length, he says, is about half an hour.

In the chapter on catechesis, Loehe gives excellent advice on how to teach. Despite his reputation, the chapter on liturgics does not make the case for his high church preferences. Rather, he says that pastors should attend to what his congregation is ready for, not going to extremes and being careful how elements are introduced to the congregation. His chapter on pastoral care is filled with good ideas, both for the pastoral care of the congregation as a whole and for individuals. His chapter on the specific task of pastoral care of the sick is full of outdated 19th century medical advice, but it perceptively distinguishes between physical, mental, and spiritual afflictions (including demonic temptations and possession).

Always Loehe stresses the Word of God, the Law and the Gospel (with the latter predominating), and how God works through the pastor’s vocation in bringing Christ to his people.

Modern day pastors have challenges of their own, but their vocation is the same calling that has been continuous throughout the history of the Church. To be able to hear from a pastor from a different era can help defamiliarize the work of today’s pastors, who can thus have much to learn from an experienced, insightful brother pastor such as Wilhelm Loehe.

Photo of Wilhelm Loehe credit: The original uploader was Bwag at German Wikipedia (Heiligenlexikon.de, transfered from de.wikipedia) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons. This version is from Pastoral Meanderings.