Roman Catholics venerate Mary, the mother of Jesus, with many titles: Queen of Heaven (the notion that she reigns with her Son), Immaculate Conception (indicating the belief that she was born without original sin), Co-Redemptrix (the view that she is the co-redeemer with her Son). These reflect what Protestants consider the outsized role that Mary plays in Catholic theology and piety. But even non-Catholics can accept some of her titles: “Blessed” (as in “all generations will call me blessed” [Luke 1:48]); “Virgin” (Matthew 1:23); and “Mother of God” (or, in Greek, Theotokos).

My fellow Patheos blogger, G. Shane Morris at Troubler of Israel has written an illuminating post entitled Yes, Fellow Protestants, Mary is the Mother of God (It’s Good Christology). To call Mary “the Mother of God” is not venerating her, as such. Rather, it confesses orthodox Christology, particularly aspects that are important for Lutheran theology.

Let’s let Shane explain it:

The mid fifth century saw a showdown between two presbyters (who also held the patriarchates of their respective cities), Cyril of Alexandria and Nestorius of Constantinople. These clergymen represented two sides in a debate over the relationship between Christ’s human nature and divine nature.

Both sides claimed to adhere to the Nicene Creed, the product of the first ecumenical council, which condemned the Arian heresy and codified the doctrine of the Trinity as all Christians today confess it. Nestorius agreed in theory that Jesus was truly God the Son, Second Person of the Trinity, and truly man, but he emphasized the distinctiveness of the two natures so much that he created, in effect, two persons: Jesus the man, and Jesus, the Son of God. The word he used for this apparent (but not actual) union of divinity and humanity was “prosopon,” a term for actors’ masks in Greek theater. In other words, Jesus of Nazareth, the person the first Christians saw, heard, followed, and touched on earth, wasn’t necessarily the same person as God the Son. The things that were said about Christ couldn’t necessarily be said about the Son.

Cyril of Alexandria became the chief opponent of Nestorius and exponent of the orthodox view. What’s surprising is that he did so using a single title not for Jesus, but for His mother, the virgin Mary. That title was “thetokos“–mother of God. Though Cyril didn’t come up with the title (it was already centuries old by that time), he used it brilliantly to smoke out Nestorius’ heretical views about Jesus.

Nestorius, you see, couldn’t use the term “mother of God,” because he didn’t think the “God” in Jesus was sufficiently united to the “man” to use them as a subject with the same predicates. Christ may have hungered, but in Nestorius’ view, God the Son did not. Christ may have slept, but God the Son did not. Christ may have died, but God the Son did not. Christ may have had a mother, but God the Son did not. So Nestorius invented an alternative title for Mary that allowed for his view: “Christotokos”–mother of Christ.

Cyril and the Alexandrians were having none of it. And once Byzantine emperor Theodosius II called the Council of Ephesus to settle the matter, Nestorius was quickly stripped of his office and his views condemned as heresy. Cyril’s view–that the natures of Christ were united perfectly but remained distinct in one Person, Who could rightly be said to hunger, sleep, suffer, die, and have a mother, all while remaining fully God–went on to inform the Council of Chalcedon in 451.

Flash forward a thousand plus years to the sacramental controversies between Luther and Zwingli. How could the body of Christ be on the altars of churches all around the world? Zwingli said that only the human nature of Christ has a body and that body was taken up into Heaven, so that it is not here anymore.

Luther said that the divine nature and the human nature come together in the person of Jesus Christ, forming a “personal union.” Thus, there is a “communication of attributes.” That is, the attributes of the divine nature and those of the human nature are shared with each other in Christ.

God is omnipresent; human bodies are spatially located. But the ascended Christ, who now fills all things (Ephesians 1:23) is omnipresent in both of His natures. Thus, His body can be many places at once.

The Incarnation means that what is said of one nature can be said of the other. God, as such, cannot die. But Jesus died. So, because of the personal union, we can say that God died. God, as such, has no mother. But Jesus had a mother. And because Jesus is God in the flesh, we can say that Mary is the Mother of God.

The Lutheran confessions address these issues and this kind of language explicitly. As we have discussed, Lutherans insisted that the Incarnation is such that it is appropriate to say that “God suffered” and “God died.” This was in opposition to some Reformed theologians who taught that only the human nature of Christ suffered and died. Some went on to maintain the extra Calvinisticum, the notion that God the Son was not completely incarnate in Jesus, that the divine nature of the Second Person of the Trinity continued to reside in Heaven even while He was partially joined with the human nature of Jesus. To Lutherans, such a distancing of the two natures is Nestorianism.

All of this is discussed in the Formula of Concord, Article VIII, “The Person of Christ,” both in the Epitome and in the Solid Declaration. This is what the Lutheran confessors say about Mary:

We believe, teach, and confess that Mary conceived and bore not a mere man and no more, but the true Son of God; therefore she also is rightly called and truly is the mother of God. (Epitome, VIII.12)

Mary, the most blessed virgin, did not conceive a mere, ordinary human being, but a human being who is truly the Son of the most high God, as the angel testifies … Therefore she is truly the mother of God … (Solid Declaration, Article VIII)

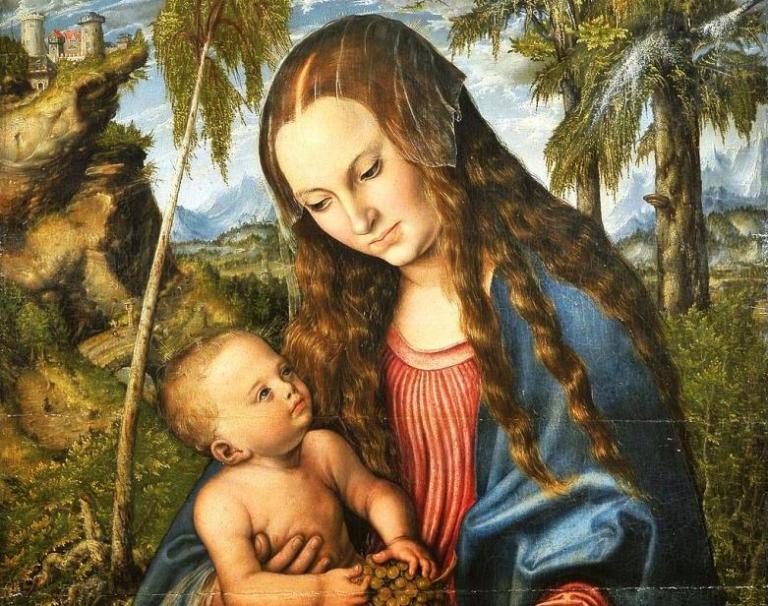

Painting, detail from “Madonna under the Fir Tree,” by Lucas Cranach the Elder [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons