Ebenezer Scrooge was NOT a hard-hearted greedy capitalist. Rather, he was an advocate of the scarcity economics of Thomas Malthus. Charles Dickens’ “Christmas Carol” actually takes the side of free market economics.

So says Jerry Bowyer in Malthus and Scrooge: How Charles Dickens Put Holly Branch Through The Heart Of The Worst Economics Ever, published in Forbes Magazine around this time in 2012. (Thanks to my daughter, Deaconness Mary Moerbe for discovering this article and showing it to me.)

Malthus (1766-1834) started with the assumption that resources are limited and that population growth will just use them all up. Increased food production, he said, will make possible a bigger population, with more mouths to feed. Want and scarcity are inevitable, as resources are used up. Poverty comes from the “surplus population,” which will drag down the rest of society unless we can bring down the birth rate.

Bowyer sees a Malthus allusion in Scrooge’s reply to the gentleman collecting money to help the poor at Christmastime, who said that many of them would rather die than go to the workhouses. “‘If they would rather die,” said Scrooge, “they had better do it, and decrease the surplus population.'”

Arguing against Malthusian economics was Jean Baptiste Say, a French economist and disciple of free market theorist Adam Smith. He showed that an increased population can mean increased productivity and that a global free market produces an abundance of resources. (See his Letters to Thomas Robert Malthus on Political Economy and Stagnation of Commerce.)

Bowyer cites the Ghost of Christmas Present as an image of abundance in contrast to Scrooge’s self-imposed stinginess despite his wealth. The Ghost takes Scrooge to the market:

“There were great, round, pot-bellied baskets of chestnuts, shaped like the waistcoats of jolly old gentlemen, lolling at the doors, and tumbling out into the street in their apoplectic opulence. There were ruddy, brown-faced, broad-girthed Spanish Friars… There were pears and apples, clustered high in blooming pyramids; there were bunches of grapes, made, in the shopkeepers’ benevolence to dangle from conspicuous hooks, … there were piles of filberts, mossy and brown, … there were Norfolk Biffins, squab and swarthy, setting off the yellow of the oranges and lemons, and, in the great compactness of their juicy persons, urgently entreating and beseeching to be carried home in paper bags and eaten after dinner.”

This abundance comes from all over the world, made possible by free trade. When the Ghost of Christmas Present introduces Scrooge to his unfairly-compensated employee’s sickly child, Tiny Tim, even the hardened Malthusian is moved. Scrooge sorrowfuly asks if Tiny Tim is going to die. Bowyer quotes this exchange:

“What then? If he be like to die, he had better do it, and decrease the surplus population.” Scrooge hung his head to hear his own words quoted by the Spirit, and was overcome with penitence and grief.

“Man,” said the Ghost, “if man you be in heart, not adamant, forbear that wicked cant until you have discovered What the surplus is, and Where it is. Will you decide what men shall live, what men shall die? It may be, that in the sight of Heaven, you are more worthless and less fit to live than millions like this poor man’s child. Oh God! To hear the Insect on the leaf pronouncing on the too much life among his hungry brothers in the dust.”

Bowyer contrasts Scrooge’s approach to business with that of his mentor Fezziwig, as shown by the Ghost of Christmas past. Fezziwig, to whom Scrooge had been apprenticed, was generous and his business was expansive. Fezziwig took on two apprentices and hired dozens of employees, all of whom shared in his prosperity. Scrooge, though, had no apprentices and only one employee, Bob Cratchett, whose pay was incommensurate with his productivity. Scrooge, says Bowyer, “was a miser, not an entrepreneur, because his economic philosophy was a miserly one, not an entrepreneurial one.”

Charles Dickens’ economic beliefs might not be quite so clear cut. In his novel Hard Times, he writes about the plight of factory workers in the industrial revolution, and he is not so sanguine about the capitalism of his day, though his real target is utilitarian ethics.

The year after Darwin published his Origin of Species in 1859, Thomas Huxley was proposing social Darwinism. Many free marketers also began urging that the poor should just die out, letting the “fittest” survive. Darwinism itself is arguably nothing more than the application of free market principles to biology.

Dickens might be thought to be more aligned with Christian socialism or the principles of social democracy. Under the robes of the Ghost of Christmas Present, Scrooge sees two emaciated children, Want and Ignorance. The narrator comments that unless their suffering is addressed, the masses of the poor might rise up and overturn society. Whereas Marx (1818-1883) wanted that to happen in a violent revolution, Christian socialists and the pioneers of social democracy, like Dickens, wanted to help the poor in order to keep that from happening.

Then again, “A Christmas Carol” was published in 1843, well before social Darwinism and the various socialist economics took shape. Dickens was probably a social reformer like William Wilberforce, motivated a Christian ethic more than economic theories.

But still, Bowyer’s treatment is illuminating. It reminds us that Malthusian economics have come back with Paul Ehrlich’s warnings of a “population explosion,” the rise of antinatalism in liberal public policy, and the pessimistic economics of scarcity assumed by many environmentalists.

“Who, after all,” asks Bowyer, “could claim to a smaller carbon footprint than the man who tried to heat his office with a single piece of coal?”

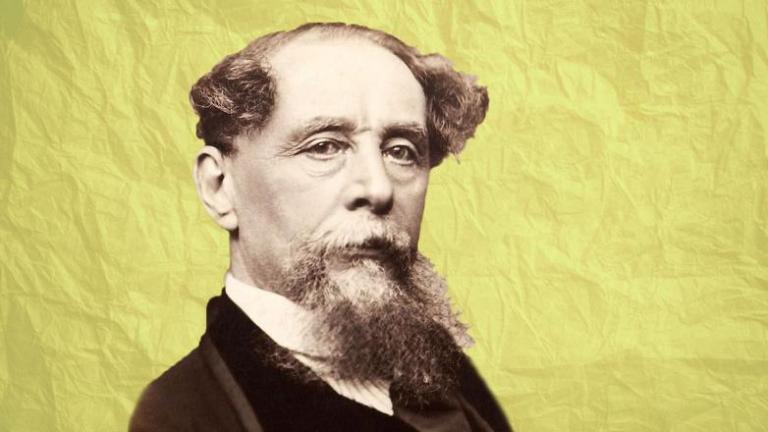

Illustration, “Charles Dickens, Hard Times, and Hyperbole,” from Gresham College via Flickr, Public Domain