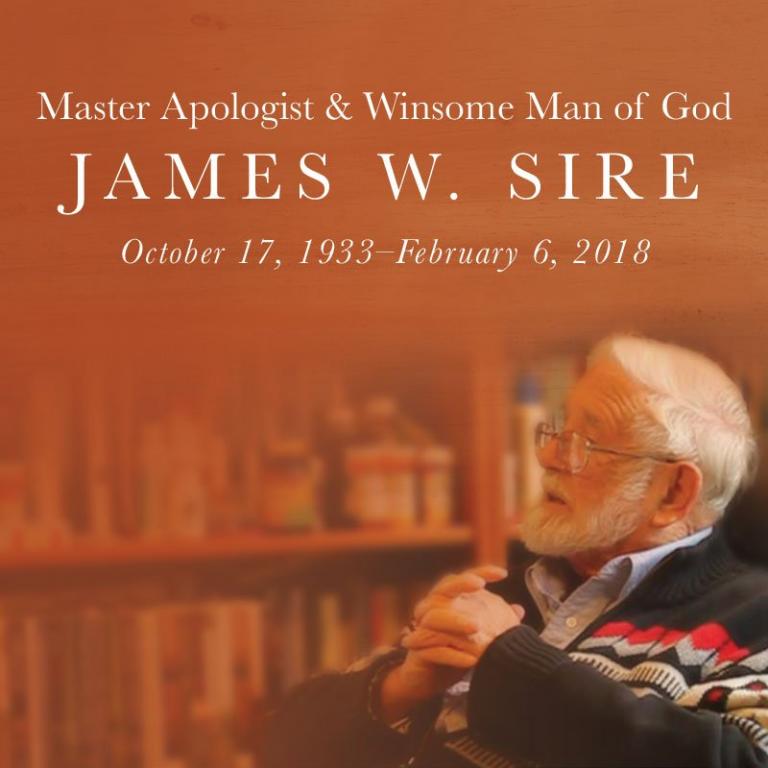

James W. Sire, the former editor of InterVarsity Press, has died at the age of 84. By his personal encouragement, his influence on my thinking, and his giving me my first publishing break, he got me started as a distinctly Christian writer.

It turns out, he did that with a lot of people, including luminaries like Os Guinness and Francis Schaeffer, whose lectures he helped turn into books. The Christianity Today obituary says this:

“Sire was a keystone in the intellectual renewal of evangelicalism in the 1960s and 70s,” wrote Andy Le Peau, a longtime editor at IVP, noting that “Sire was first to publish a number of influential figures.”

CT once called Sire a “midwife” of Schaeffer, the theologian known for founding the L’Abri community. The two met back in 1968 and went on to work together on books including Schaeffer’s How Should We Then Live? and Whatever Happened to the Human Race?, as well as transcripts of his talks.

“It was a very troubled time intellectually—evangelicals were just out of the intellectual forest and ready to battle the world. [Schaeffer] set a lot of people thinking,” Sire said.

I guess I was a minor part of that “intellectual renew of evangelicalism in the 1960s and 70s,” but it was all thanks to Sire.

I was a graduate student in English at the University of Kansas in the 1970s. By that time, I had given up the liberal theology of my raising and was a more or less evangelical Christian (not yet a Lutheran). I was struggling to relate my new-found faith with my graduate studies, my field of English literature being the trojan horse for the new postmodernist ideology. My problem wasn’t at all that graduate studies were undermining my faith. Rather, my faith was undermining my graduate studies, since I was seeing how weak, pointless, and absurd so much of it was. I still loved and was interested in literature, but I was losing interest in the study of literature as I was learning it.

One year, soon after Christmas, I went to the Modern Language Association in Chicago. I was sitting through a session of the most abysmal idiocy. My body language must have registered my disgust and I may have been guilty of asking some pointed questions, but afterwards a man sitting behind me came up, smiling, and introduced himself. He was James Sire, editor of InterVarsity Press, up from nearby Downers Grove for the conference. We were in complete agreement about the session and laughed about it. He invited me to lunch. He too had a background in literature. I knew about InterVarsity as a campus Christian group, though I wasn’t involved in any evangelical groups on campus. I didn’t really know anyone else in my field who was a conservative Christian. Just knowing him was helpful in that way. He gave me a bunch of books and put me on to other Christian scholars.

His own book, The Universe Next Door, is an introduction to different worldviews. It uses as illustrations works of literature, as well as philosophy, cultural analysis, and the arts. Sire’s worldview criticism gave me a way to study literature that tied in well to my Christian faith. I wasn’t Christianizing everything; rather, I was looking at literature in its own terms, but noting its deeper currents, seeing how they disclosed the inner dynamics, as well as inadequacies, of the author’s views of reality, indeed, the religious dimension, even of authors that seemed to have no religion. And I could see the Christian worldview playing out in writers of the past, not just in overtly Christian authors such as Dante and Milton, but in “secular” authors such as Shakespeare, whose assumptions about morality, nature, and human nature were Biblical to the core. In my studies, I started writing papers using Sire’s worldview analysis and getting good grades and praise for them. After all, attention to worldviews is kind of like postmodernism in being attuned to the diversity of thought and expression.

Anyway, we kept in touch. We had something then called letters, which were scratched out in ink on paper. When I was in the neighborhood, I’d drop in on him in his office in Downers Grove. He would take me to lunch, always picking up the tab. Then we would go into the book store at InterVarsity Press and he would just start pulingl down titles from the shelves, giving me an armload of books to take home, never letting me pay for any of them.

I got my Ph.D., found a job in a little Oklahoma state college, became a Lutheran, which distanced me somewhat from his Reformed theology and his Kuyperian methods, but we stayed friends and correspondents. In my Bible reading, I was noticing that the Scriptures actually say quite a bit about the arts. But I never heard any of these passages commented upon. I was finding answers to a number of aesthetic issues that were relevant to literature also. I was writing Jim, telling him about what I was learning.

He encouraged me write it up and to send him the results. I did. I had sent him a couple of discourses, whereupon he offered me a publishing contract! My discourses turned into chapters, and the chapters into my first book: The Gift of Art: The Place of the Arts in Scripture.

(That book is now out of print, though Amazon still has some for sale at an exorbitant price. I later included that work as part of a much larger book on the arts entitled State of the Arts: From Bezalel to Mapplethorpe.)

Anyway, that got me started. More books on many different topics followed, most of which were written for Christian publishers. This also put me in the orbit of the Christian academic world.

Some people have wondered how, as a confessional Lutheran (a group that tends to stick to their own kind), I have been able to have so many ties with the larger evangelical, conservative Christian world. That answer, as in so many other dimensions of my career, comes down to James Sire.

Now that I am retired, I find myself looking back over my life, tracing its threads and marveling at the tapestry that was Providentially woven.

Not being Catholic, I can’t pray to the saints by saying, “Thank you, Jim!” But I can express my gratitude by recounting how I was blessed by the personal interest he took in a lowly grad student, by his active and formative mentorship, by his publishing my first book, and by his starting me on my way.

If you have benefited in any way from something I have written or something we talked about in a classroom, you too owe a debt to James Sire.

Illustration from InterVarsity Press, Twitter, @ivpress