During the modernist era, from the Enlightenment through most of the 20th century, it was thought that science would answer all of our questions and dispel all of the mysteries of life. In the words of the pioneering sociologist Max Weber, the effect of science would be to “disenchant” nature, reality, and our lives.

In 1894, the physicist Albert Michelson said that “it seems probable that most of the grand underlying principles” of physics “have been firmly established and that further advances are to be sought chiefly in the rigorous application of these principles.” Then came the mind-blowing discoveries of Albert Einstein. Then came the even more mind-blowing discoveries of Quantum Physics.

The coronavirus epidemic is showing the public’s enormous faith in and yet misunderstanding of science. We are not used to being so vulnerable to a dread disease. We expect science to protect us and are confused when it does not. We expect treatments and a vaccine now, or in the immediate future. All of the conflicting models, contradictory data, and unknowns about the virus are disillusioning. We forget that science is a laborious process, necessitating long and complicated experimentation, involving the falsification as well as the confirmation of hypotheses. It takes time and working through uncertainties to do science.

I came across an article in Commentary entitled They Blinded Us With Science: The History of a Delusion by Sohrab Ahmari, who stirred up that controversy about conservatism with David French. It’s about “scientism,” the blind faith in science, and he shows that science, for all of its great accomplishments, cannot be the sole arbiter of all truth.

The essay is worth reading in its entirety. What I found especially interesting is his point that science has intrinsic limits. He draws on Marcelo Gleiser, a Dartmouth professor of physics and astronomy, an expert in particle physics and cosmology, who explains why science can never arrive at an “ultimate truth.”

For one thing, scientific observation depends upon our technological instruments–the telescope, the Hubble telescope, the radio telescope, the particle accelerator, etc., etc.–which reveal more and more, and, yet, as the technology improves, continuously force us to revise what we thought we knew.

Then there are limitations built into nature itself:

Nature foists a second set of limits on scientific inquiry. “Nature itself—at least as we humans perceive it—operates within certain limits,” Gleiser says. To cite one of many examples: Our universe’s finite age, coupled with the finite speed of light, places an absolute, and permanent, obstacle on the road to any “ultimate” scientific account of the cosmos.

There are cosmic limits beyond which we simply can’t “see,” because the distances involved are too vast, and the fastest speed in nature, that of light, all too finite. Even objects we do see, the stars and galaxies that sparkle in our night sky, are only “there” in a provisional way. Particles of light from the “nearby” Andromeda galaxy that telescopes detect today left their point of origin 2 million years ago; we can only infer that Andromeda is still there.

The limits on our knowledge of the cosmos become still more daunting when we take into account the expansion of the universe. Gleiser explains: “The farthest point from which light could have reached us in 13.8 billion years, the age of the universe. Even if space extends beyond it, we cannot receive signals from behind this wall.” And as the expansion of the universe accelerates, our cosmic bubble shrinks, relatively speaking, as more and more of the universe recedes beyond our measuring grasp.

Our universe might be closed. It might stretch out infinitely. Or it might be one of a multitude of universes floating in some incomprehensibly gigantic “multiverse.” We can’t be sure, and, Gleiser insists, we can never be sure.

Ahmari also draws on the French thinker Michel Henry. In his book Barbarism (1987), he says that science rigorously excludes everything that is “subjective.” And yet, that excludes most of life, since our actual experience of living is largely subjective.

The scientific outlook, Henry argues, subtracts our subjective experience of life from our understanding of life. Since much of life doesn’t lend itself to objective apprehension and expression, the scientific outlook simply removes what it can’t apprehend from the realm of what is knowable or even worth knowing. But this brute privileging of one form of knowing above all others ultimately ends up erasing the truly human subject as such. Warned Henry: “To separate the reality of objects from their sensible qualities is also to terminate our senses, all of our impressions, emotions, desires, passions, and thoughts; in short, all of our subjectivity that makes the substance of life”. . . .

[Science] tears down all traditional knowledge, including the subjective knowledge embedded in human life itself; it rejects communion with the past, except, that is, on scientific-technical terms. This, even though life itself long predates science as we know it. Life should, in a rightly ordered cultural scheme, enjoy primacy over what is merely one branch of knowledge, one way of knowing. By life, Henry doesn’t mean “biological life,” which is another scientific category, but something closer to being-humanness. Life, in this sense, entails religion, spirituality, art, culture, folkways, and, more fundamentally, the knowledge embedded in our daily experience.”

Again, to recognize the limits of science is not to denigrate science in any way. It is simply to acknowledge what science is.

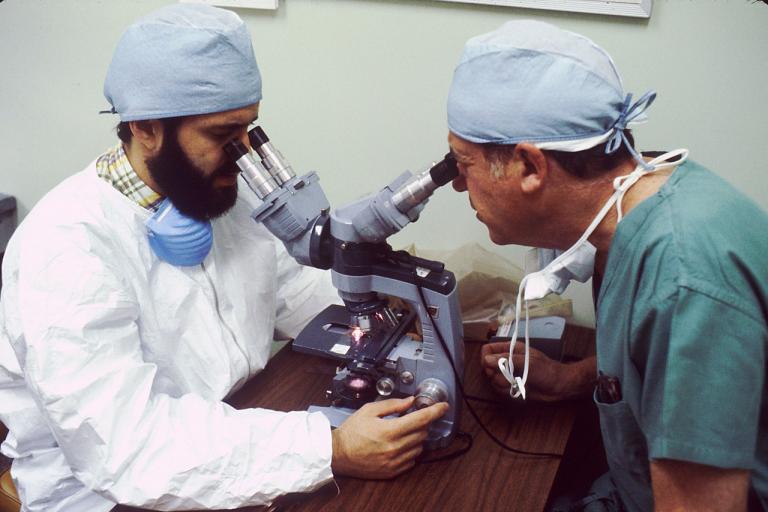

Image by Welcome to all and thank you for your visit ! ツ from Pixabay