Last week was the Jewish holiday Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement. Since there is no Temple today, it cannot be celebrated as called for in Leviticus 16, with the high priest entering into the Holy of Holies to pour sacrificial blood onto the Mercy Seat of the Ark of the Covenant that contains the tablets of the Law. Today, Jews mark the day with penitential prayer, fasting, and other solemn observances.

One Yom Kippur custom that Jews have is to apologize to people whom they have wronged and to ask and bestow forgiveness. That’s a good practice, and one that Christians also are often encouraged to do.

I quite randomly came across an article in the Times of Israel that makes the observation that no one in the Bible is ever recorded doing that.

There are cases of people resolving conflicts with each other, but they don’t take the form of anyone saying, “I’m sorry for what I did to you” and the other person saying, “That’s OK, I forgive you.” Rather, they are resolved with a kiss and with weeping from both parties.

The author, Joshua Berman, professor of Bible at Bar-Ilan University, looks at the accounts of Joseph and his brothers who sold him into slavery, Jacob and his brother Esau whom Jacob had swindled out of his birthright, and David and his son Absalom who had slain his brother for raping his sister. In the course of his discussion, he distinguishes between forgiveness and reconciliation.

From Joshua Berman, No Apologies, Just a Kiss (my bolds):

Social psychologists teach us that when it comes to rupture and repair in human relations, there are two types of cultures. There are cultures of forgiveness and cultures of reconciliation.

Cultures of forgiveness are usually cultures with a strong sense of the individual. The offense was unfair and unjust. It creates a debt to the aggrieved. The apology of the offender allows the release of guilt. The apology pays off the debt and heals the insult and the injury. It allows for the aggrieved to achieve emotional closure. . . .The forgiveness offered by the aggrieved is an act of empathy with the contrition of the apologizing offender.

By contrast, cultures of reconciliation tend to focus on the collective. Who I am is entirely bound up by who we are, the bonds we share, and the common goals to which we aspire. When a relationship is ruptured, a premium is placed on re-achieving harmony with those around me. Here, value is placed on letting go. . . .

Cultures of forgiveness emphasize the peace within us; cultures of reconciliation emphasize the peace between us. Cultures of forgiveness seek to clear the air about what transpired between the parties. In cultures of reconciliation, the air about what exactly happened is clouded by the smoke of the proverbial peace pipe.

The world of the Bible places a premium on reconciliation. For the stability of the family and of the kingdom, David cannot afford a rupture with his son Absalom. Joseph cannot afford a rupture with his brothers if he is to serve his mission as their guardian and if they are to face the challenge as a minority culture in Egypt. Esau values his relationship with his only brother, his twin, Jacob. In none of these stories are the injuries and injustices of the past examined, aired before the aggrieved and the subject of apology. In each of these cases, the parties exist in a hierarchy whereby the offender submits to the aggrieved. Absalom, the brothers, and Jacob all bow before the party they wronged, though not necessarily with reference to the injury they caused, but because of their inferior status. And in all three cases, the party with the higher status – the aggrieved party – seeks to bring harmony to the relationship – never by demanding contrition, but simply by offering a kiss – the kiss of reconciliation, a potent, non-verbal sign: we are too important to each other to allow this continue. We are good.

Now when Prof. Berman refers to the Bible, he is, of course, speaking of the Old Testament. The New Testament speaks of both forgiveness and reconciliation.

Jesus says that we are, as individuals, to ask for and to grant forgiveness to those who have wronged us. “’Lord, how often will my brother sin against me, and I forgive him?'” asked Peter, “‘As many as seven times?’ Jesus said to him, ‘I do not say to you seven times, but seventy-seven times'” (Matthew 18:21-22). And forgiving others is tied to the forgiveness we need from God. As we pray in the Lord’s prayer, “forgive us our trespasses, as we forgive those who trespass against us” (Matthew 6:12). And what we individuals receive from God, through the atonement of Christ, is forgiveness for our sins (Ephesians 1:7; Colossians 2:13; etc., etc.).

But Christ also gives us reconciliation with God and we are called to be reconciled to each other (my bolds):

For if while we were enemies we were reconciled to God by the death of his Son, much more, now that we are reconciled, shall we be saved by his life. More than that, we also rejoice in God through our Lord Jesus Christ, through whom we have now received reconciliation. (Romans 5:10-11)

For in him all the fullness of God was pleased to dwell, and through him to reconcile to himself all things, whether on earth or in heaven, making peace by the blood of his cross. And you, who once were alienated and hostile in mind, doing evil deeds, he has now reconciled in his body of flesh by his death, in order to present you holy and blameless and above reproach before him, (Colossians 1:19-22)

It isn’t just that we have done bad deeds that need to be forgiven, though this is part of it. On a bigger scale, our relationship to God is ruined. Indeed, God’s relationship with the world is damaged. The Colossians text suggests that it is the incarnation–the fullness of God dwelling in Christ’s body of flesh–and Christ atonement on the cross that reconciles “all things” to God. That includes those of us who have been “alienated” from God and who have been “hostile in mind” to Him. Through God’s incarnation and death, He is reconciled to us, and we are reconciled to Him.

And, like forgiveness, our reconciliation with God through Christ is connected to our being reconciled with our fellow human beings:

All this is from God, who through Christ reconciled us to himself and gave us the ministry of reconciliation; that is, in Christ God was reconciling the world to himself, not counting their trespasses against them, and entrusting to us the message of reconciliation. Therefore, we are ambassadors for Christ, God making his appeal through us. We implore you on behalf of Christ, be reconciled to God. (2 Corinthians 5:18-20)

Thus, Jesus says in the Sermon on the Mount, “if you are offering your gift at the altar and there remember that your brother has something against you, leave your gift there before the altar and go. First be reconciled to your brother, and then come and offer your gift (Mattheww 5:23-24).

Our relationships and not just our individual selves need healing and restoration. How do we do that? We’ll pick up that discussion in tomorrow’s post.

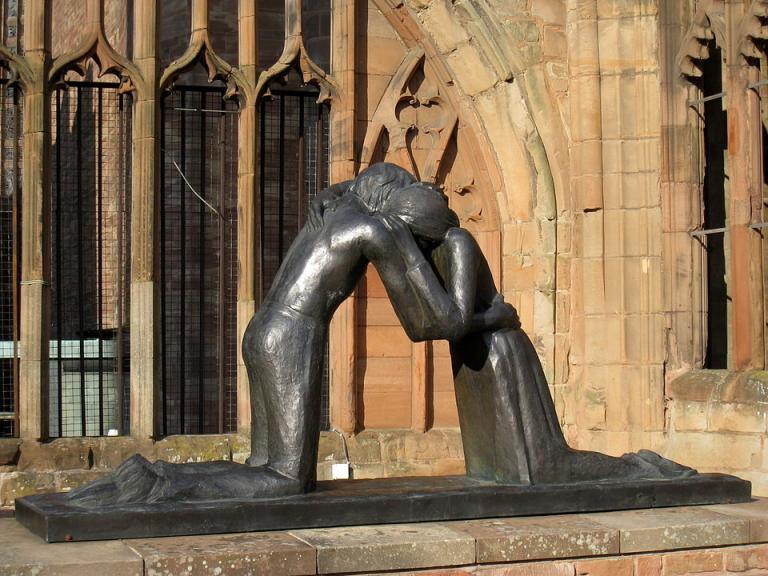

Photo: Reconciliation by Josefina de Vasconcellos, in St. Michael’s Cathedral, Coventry, photo by Martinvl – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=46444357