Churches took one approach to relating to the culture when it was pro-Christian. It took a different approach when the culture became religiously neutral. But what approach should it take when the dominant culture is actively opposed to Christianity?

This is the theme of an important essay by Aaron Renn, published in First Things and entitled The Three Worlds of Evangelicalism.

Focusing on evangelicalism, he surveys the practices and tactics that Christians have been employing as the religious climate in the culture has been changing. You need to read the essay in its entirety for its details, evidence, and nuances. I will quote his three phases and briefly summarize the church’s response to each one:

- Positive World (Pre-1994): Society at large retains a mostly positive view of Christianity. To be known as a good, churchgoing man remains part of being an upstanding citizen. Publicly being a Christian is a status-enhancer. Christian moral norms are the basic moral norms of society and violating them can bring negative consequences.

Some Christians did get involved in politics, taking advantage of the positive cultural climate under the banner of the “Moral Majority,” the assumption being that they constituted the “majority.” They successfully made themselves key players in the Republican Party, with the high water mark being the takeover of the House of Representatives in 1994.

Evangelicals’ strategy for reaching this positively-inclined culture was “seeker sensitivity.” This resulted in the Church Growth Movement, with its “seeker sensitive” approach to worship, preaching, music, and church in general. The assumption, though, was that non-Christians were “seekers,” who would be glad to be reached. This too met with success with the rise of megachurches.

- Neutral World (1994–2014): Society takes a neutral stance toward Christianity. Christianity no longer has privileged status but is not disfavored. Being publicly known as a Christian has neither a positive nor a negative impact on one’s social status. Christianity is a valid option within a pluralistic public square. Christian moral norms retain some residual effect.

As the society became more and more secularized, the new strategy became cultural engagement. Christians would take a positive stance towards culture–the arts, academia, law, the government–and interact with it on its own terms, in an attempt to exert a Christian influence. This approach too enjoyed some success, as many Christians entered the professions and became part of elite social institutions.

- Negative World (2014–Present): Society has come to have a negative view of Christianity. Being known as a Christian is a social negative, particularly in the elite domains of society. Christian morality is expressly repudiated and seen as a threat to the public good and the new public moral order. Subscribing to Christian moral views or violating the secular moral order brings negative consequences.

The Supreme Court’s Obergefell decision legalizing same-sex marriage marked a new phase of cultural hostility to any kind of orthodox Christianity. Even evangelicals who sought to engage the culture could not go along with the LGBTQ revolution and found themselves cancelled and otherwise threatened with expulsion from polite society.Churches have not fully faced up to this new climate, Renn says, but we can see several contending–but related–responses.

One is to fight the hostile culture. This impulse manifests itself in evangelicals’ support for Donald Trump, even when that involves stepping away from traditional moral criteria for leaders in favor of a realpolitik that will combat progressivism and advance Christian interests, such as the pro-life cause.

Another is fighting within churches, as some members seem to bring views dominant in the culture (such as critical race theory, social justice ideology, feminism, and other progressive ideologies) into the church so as to correct what the culture is criticizing. The fight to do so is met with fighting back from members on the other side of these issues..

The third response is the “Benedict Option,” in which Christians disengage themselves from the hostile culture to build alternative social structures (schools, families, communities, art, intellectual projects) of their own.

Renn concludes,

The future of the cultural engagers and megachurch people who have turned toward cultural synchronization looks grimmer [than the culture warriors]. The much-discussed failures of the evangelical elite cannot be understood without reference to the way the ground rapidly and fundamentally shifted under them during the transition to the negative world. Their desire to remain members in good standing of secular elite society, their social-gospel focus, and their embrace of current secular academic theories are reminiscent of what happened to the mainline denominations (though this time the secular theories are from the social rather than natural sciences). . . .

But rather than extend existing strategies forward into the future, evangelicals could, and should, grapple seriously with what it means for them to live in the negative world. What strategies should be employed for this era? Unlike previous eras, the negative world necessitates a variety of approaches to match the diversity of situations in which American Christians find themselves. Finding a path forward will probably require trial and error and a new set of leaders with different skills and sensibilities.

Renn says he is trying to do this with his American Reformer project and website (which published the article The Lutheran Option that we blogged about).

So what is the “path forward”? I welcome your ideas.

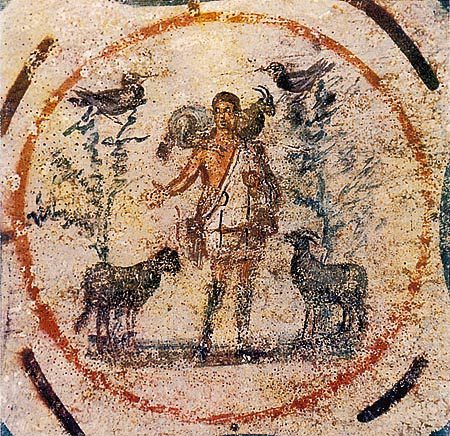

It seems to me that we should study and draw on the example of the early church, which faced an even more negative cultural climate and yet thrived and eventually converted the hostile society. We have much to learn here, including how the early Christians won over the Roman public by their radical virtue. But another factor was the popularity of Christianity among slaves, women, and the lower classes of Roman society.

Not all of American culture is “negative” towards Christianity. Just our cultural elite. Though the most unchurched demographic is the white working class, they, on the whole, are not particularly hostile to Christianity. Churches might focus their outreach effort not so much on the affluent middle class or the culturally elite, but on blue collar Americans in blighted cities, boarded up small towns, and struggling rural areas. Yes, these folks, whom progressives used to cultivate but now look down upon as “deplorables,” are largely Trump supporters. And, yes, they are entangled with moral problems, including drug addiction and sexual promiscuity, though many of them recognize themselves as casualties of this kind of behavior. If Christians and churches would abandon concern for their social status, they could find themselves ministering to the “poor”–not idealized victims but human beings with hard lives and rough edges–who could be surprisingly receptive to the Gospel.

Also, as those phases show, culture changes and it changes rapidly. The ideas and the influence of the “Negative” phase may not last, as formidable as they seem. Though progressive politicians are in power and though the Left is dominating the public square, notice how all of their initiatives have been failing. A backlash seems to be building. As I show in my book Post-Christian, postmodern thought and movements such as the sexual revolution are running into crises and self-contradictions, proving themselves to be untenable and themselves in search of change. What might emerge next is unclear, but Christians may well have an opportunity to contribute to the “post-secular” era that some observers are heralding. In that case, what Christians need to do is hold on–be faithful, don’t give in, don’t give up–and wait.

Illustration: “The Good Shepherd,” Catacombs of Rome (3rd century) http://www.xanthi.ilsp.gr/istos/walls/thesi/thesi_1.htm, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=515973