The Anxious Bench, a Patheos blog run by various Christian historians, recently published a fascinating post by Nadya Williams, a professor of ancient history at Western Georgia University, entitled Created for Work?: The Cost of Leisure and the Privilege of Work in Antiquity and Today.

She discusses the concept in ancient Rome of otium, or leisure, as opposed to negotium, or busy-ness. “Otium was held to be the ideal state of existence in Roman society,” she observes, “for this leisurely state of being was essential for philosophical reflection, writing, and any meaningful life of the mind.”

Though the Roman playwright Ennius and the statesman Cato the Younger argued that an excess of otium was just as bad as an excess of negotium, Romans still tended to prize the former and look down upon the latter. These values had a particular consequence. Prof. Williams writes,

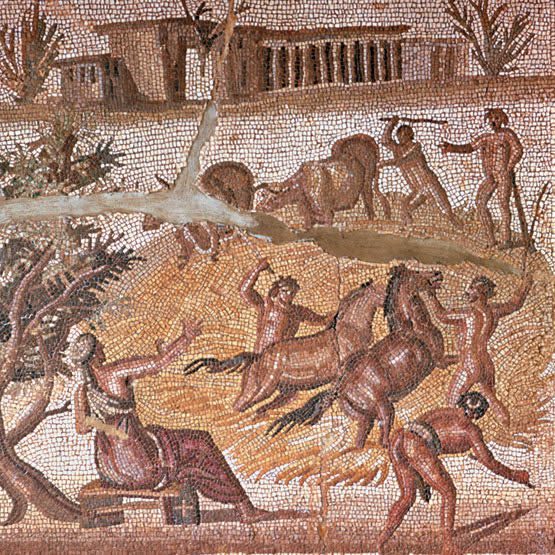

When we reflect on the Roman ideal of otium, we have to keep in mind that it could only exist if someone else took some of the negotium off your hands. Put plainly, Roman otium was only made possible by the existence of slavery.

She goes on to write about the Roman institution of slavery–based not on race, but on the subjugation of conquered people–a system so extensive that even some slaves owned slaves.

If the pagan Romans, as well as the Greeks, favored otium, Christianity, with its doctrine of vocation, put a great value on work, including manual labor (1 Thessalonians 4:11).

Thus, going outside the scope of Prof. Williams’ post, when Rome fell and Christianity began to be culturally influential, the slavery of pagan Rome faded, though some aspects of it arguably continued with the rise of serfdom, though medieval peasants were never considered property and enjoyed certain rights that slaves never did.

Still, the greater status of otium remained with the feudal social classes. You find it as late as 19th century novels, which sometimes portrays an aristocratic family being scandalized if their daughter fell in love with a “tradesman.” Or if a younger son of a noble family went into “business.”

Slavery–this time based on race–was brought back, though, by Spanish, Portuguese, and later English colonists in the New World, who demanded vast amounts of labor to work their plantations. They became complicit with the Muslim slave trade, which reflected the continued practice of slavery throughout the Islamic world, and then started their own brutal slave trafficking. The Catholic Church condemned this new slavery, though many Catholics ignored that teaching, just as many Catholics today ignore the church’s teaching about abortion.

This was during the classical revival of the 16th and 17th century, which, in its humanist as opposed to its Reformation form, may have brought not only the good but some of the bad elements of the Greeks and the Romans to the fore. Such as an unhealthy respect for otium, looking down on those who did the actual work, and selling out for slavery.

Protestants in Northern Europe, evangelical Anglicans in England, and Puritans in America tended to be the driving force in the abolitionist movements in the 19th century. These are the Christians who would have had the most robust appreciation of the doctrine of vocation.

I realize that the issue is complicated, with plenty of failures and inconsistencies to go around. Some Christians argued that being a slave is a vocation, confusing the Greco-Roman institution cited in the New Testament with the slavery of the new world, which consigned a whole race to slavery with no provision for individual callings.

Certainly, there is room for otium in vocation, as we see in the mandates for rest in the Biblical ordinance of the Sabbath. And vocation is not a matter of constantly being busy, as we see in Christ’s admonition to Martha, with her negotium, and His praise of Mary taking time to sit at His feet (Luke 10:38-42). And in the Gospel, all Christians have rest from their works (Hebrews 4:9-10).

After all, the whole point of vocation is that God is the one who is working through human beings, as they love and serve each other.

Today, though, we seem to have both an obsession with otium and a life of often meaningless negotium. Vocation can help us sort those out and can bring freedom, both for ourselves and for others.

Illustration: Mosaic of Roman slaves performing agricultural tasks, Historym1468, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons