I read a wonderful essay by Nadya Williams about Dorothy L. Sayers. If you aren’t familiar with Sayers, a British writer and scholar who lived from 1893 to 1957, you should become so.

She was the author of some first-rate Christian apologetics, similar to that of her friend C. S. Lewis. (See Creed or Chaos and the collection Letters to a Diminished Church: Passionate Arguments for the Relevance of Christian Doctrine.) She also wrote one of the best contributions to the field of Christian aesthetics in Mind of the Maker, in which she closely ties human creativity to the creativity of the Creator, finding analogies to the artistic process in the doctrine of the Trinity.

As if that weren’t enough, she was the catalyst for revival of the classical education movement with her essay The Lost Tools of Learning.

Perhaps her greatest achievement was her translation of Dante’s Divine Comedy (Hell, Purgatory, Paradise), in which she manages to carry over into English Dante’s terza rima, the interlocking three line stanzas rhyming aba, bcb, cdc, etc., etc. It is much easier to find rhymes in the Italian language than in English, and yet somehow Sayers pulls it off, thus keeping the form as well as the meaning of the great Christian epic.

Furthermore, the best guide to Dante has to be Sayers’ Introductory Papers on Dante. Just as Virgil explains the realms of the afterlife to Dante, Sayers explains Dante’s writings about the realms of the afterlife to the modern reader. Underscoring that the work is an allegory, not a travelogue, Sayers unpacks the spiritual meaning and insights of the poem, which even us non-Catholic Christians can appreciate.

Sayers is best known, though, for her Lord Peter Wimsey novels, which established her as a pioneering novelist of the mystery genre, on a par with Agatha Christie.

Williams is one of the Christian historians who contributes to the Patheos blog The Anxious Bench. Her post about Sayers, entitled Dorothy Sayers Solves Her Scandal of the Evangelical Mind, focuses on this incredibly talented woman’s career path. She begins:

In the wake of WWI, a brilliant woman in search of an income found herself in a quandary. Here she was, a woman in a man’s world, and therefore unable to become a professor—a path she would have likely pursued, had she been born half a century later. She was, nevertheless, someone prone to live inside her head, dwelling less comfortably with people than with her intense and deep ideas about so many topics, from the Greco-Roman Classics to Dante’s poetry to French literature and, most of all, theology and God’s claims on her life.

So she became an advertising copy-writer. This enabled her to make a living through her facility with words. “But this time in her life was not wasted. Rather, she used this period to solve her own crisis of the evangelical mind and in the process, perhaps not even quite realizing it at the time, she determined the track that the rest of her life took.”

She knew that writing cringey ads pays, but writing poetry or very serious academic books doesn’t. But she also knew that she did not want to spend the rest of her life as a copywriter. So, she found a middle road that ended up being more financially successful than perhaps she ever expected: writing crime novels. This road, at least, involved less of an intellectual selling out in her view than writing copy for Guinness ads. And it freed her over time to do the kind of earnest theological writing and translation work that she really wanted to do all along.

But there is an irony of sorts in that fateful decision that Sayers made to create Lord Peter Wimsey, a hero who turns 100 this year, and whose crime-solving antics she herself, his very maker, saw at times with such disdain. You see, because the Peter Wimsey novels turned out to be the most profitable writing Sayers ever did—read by the greatest number of people of all her works in her lifetime, at least—her name became so associated with his that even today, the website of the official Dorothy L. Sayers Society introduces her as “renowned English crime writer.”

Though overshadowed by her popular fiction, Sayers did, in fact, use Lord Peter to bankroll her scholarly projects.

Williams’ post is especially poignant because she herself recently walked away from a tenured full professorship at a secular university, both because it was making her miserable and in order to spend more time with her family. She tells about her decision in her post Discerning Vocation: Walking Away from Academia.

In the Sayers post, she shows how Sayers fulfilled her true vocation by pursuing work that seemed to have little to do with her vocation. She points out that in the world of specialized academic research, a scholarly tome that was the work of years may be read by fewer than a hundred fellow specialists. Whereas writing for the general public, as Sayers did, can reach and have an impact on multitudes.

Williams celebrates the vocation of the “independent scholar.” Freed from the narrow specialization required for academic careers, Ph.D.s are positioned to be “public intellectuals.” There will be more and more of these, not only because there are few academic jobs for humanities specialists but, I would add, because the state of academia today is driving many true scholars away. I notice that Williams herself is pursuing this route, and I wish her the best.

In my career, I did both kinds of writing, but found an academic haven in Christian colleges, which supported my more popular writing that has proven to be of far greater consequence.

Are there other examples of people finding their vocation by losing their vocation? Do any of you have experience with this?

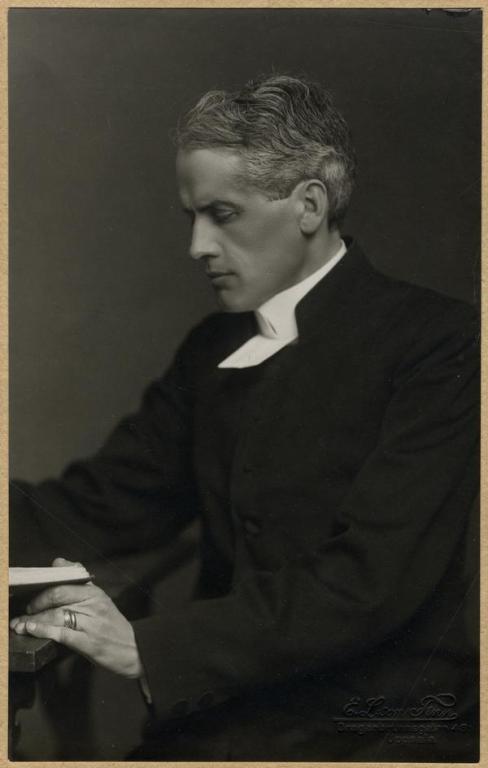

Dorothy L. Sayers (1928) by http://www.biography.com/people/dorothy-l-sayers-9472925, Fair use, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=34552819