In the wake of WWI, a brilliant woman in search of an income found herself in a quandary. Here she was, a woman in a man’s world, and therefore unable to become a professor—a path she would have likely pursued, had she been born half a century later. She was, nevertheless, someone prone to live inside her head, dwelling less comfortably with people than with her intense and deep ideas about so many topics, from the Greco-Roman Classics to Dante’s poetry to French literature and, most of all, theology and God’s claims on her life.

Sure, the myth persists today that degrees in English or other literatures are worthless; apt to leave one broke, unemployed, and unemployable. This is a lie as much in our own age as it was in Sayers’. You see, every advertising agency or company selling any kind of goods needs a copywriter.

The copywriter’s job is far from glamorous, but just think of all these words with which we are besieged on every side today—on roadside billboards, on websites for every product imaginable, on ads that troll us on social media. Someone has to write all these words, painstakingly making sure that they read smoothly, are free of error, and hopefully portray the product enticingly enough to get readers to buy it. This someone is a career writer, most often a proud owner of a degree in English or literature with dreams and aspirations of becoming the next J. K. Rowling or Dante or Keats. Instead, here they are, writing eloquent ads for meatless breakfast sausages, absolutely leak-proof diapers, and toilet paper so soft even the bears love it.

It is mind-blowing to imagine in retrospect, as we think of Dorothy Sayers as who she became by the end of her life—a best-selling crime writer, translator of Dante’s Divine Comedy, and a public intellectual par excellence—that for a decade (from 1922 to 1931), she was primarily a copywriter for an advertising agency.

Sayers was never content to be peddling mustard and beer—as characteristically elaborate and witty as her jingles for such products were. But this time in her life was not wasted. Rather, she used this period to solve her own crisis of the evangelical mind and in the process, perhaps not even quite realizing it at the time, she determined the track that the rest of her life took.

The key question that she faced during this rather low time in her life was: what should an intellectual woman do to make ends meet if she feels called to a life of the mind, yet the traditional careers that most readily offer such a life are closed to her? Her dilemma is a remarkable example of plus-ça-change. As I wrote recently in another essay, the new and future crisis of the evangelical mind involves not academics, but independent scholars. Unable to get the jobs for which their Ph.D. prepared them, many still want a life of the mind. And, of course, others (like myself or, to name a more prominent example, Karen Swallow Prior) resign from academic positions that were not designed for human flourishing. For all who struggle with these questions, seeking a life that would allow them to use their mind for the glory of God, Sayers’ trajectory offers food for thought, even as her path is not one that is perfectly replicable at will.

For Sayers, the initial solution involved a brilliant compromise. She knew that writing cringey ads pays, but writing poetry or very serious academic books doesn’t. But she also knew that she did not want to spend the rest of her life as a copywriter. So, she found a middle road that ended up being more financially successful than perhaps she ever expected: writing crime novels. This road, at least, involved less of an intellectual selling out in her view than writing copy for Guinness ads. And it freed her over time to do the kind of earnest theological writing and translation work that she really wanted to do all along.

But there is an irony of sorts in that fateful decision that Sayers made to create Lord Peter Wimsey, a hero who turns 100 this year, and whose crime-solving antics she herself, his very maker, saw at times with such disdain. You see, because the Peter Wimsey novels turned out to be the most profitable writing Sayers ever did—read by the greatest number of people of all her works in her lifetime, at least—her name became so associated with his that even today, the website of the official Dorothy L. Sayers Society introduces her as “renowned English crime writer.”

I am not telling this story, to be clear, to say that all of us refugees and/or inadvertent rejects from academia need to come up with brilliant crime series of our own as a way of supporting ourselves in this career change. Rather, Sayers’ experience provides another important takeaway: the kind of writing that we are free to do outside of academia is different than what academia traditionally demands and rewards. This freedom can be a wonderful blessing. It can also allow us to reach and serve a lot more people with our hard-won academic expertise—if only we know how to translate the academic writing style of our graduate school years into something more readable.

While at most institutions, it is the peer-reviewed jargon-laden academic articles and monographs that are rewarded with tenure, very few outside of academia read some (many) of these books. I know academics whose really excellent books published with top university presses have sold fewer than one hundred copies. Such a fate also regularly awaits scholarly articles in paywalled scholarly journals. Mind you, these publications ARE very important, and researchers writing both for academic audiences and for popular ones rely on these ground-breaking studies. But we also need to be realistic about the economics of university press publishing. Most university presses are non-profits, and the scholars who publish for them usually have a paying academic job. I remember one of my professors at Princeton remarking about receiving a royalties check for slightly under $5 one year from Oxford University Press. When his lawyer wife laughed, he added: this royalties total was for two books.

But those who leave academia do not have the luxury of spending years of their life on writing pathbreaking books that will be read only by a few academics–they must be mindful of those same pesky concerns about income that drove Sayers crazy until she found a way to resolve her own crisis of the evangelical mind. And so, here’s the other way to see this. Those scholars outside of academia do not have to be bound by the same expectations vis-à-vis writing and publishing as their tenure-track and tenured colleagues. I am never going to write an academic article again. Rather, I regularly write essays for public-facing magazines, journals, and blogs, presenting my research and ideas for a broader audience.

And that is exactly what Sayers did, beginning already with her Peter Wimsey series. Reading her crime novels, one cannot miss all the quirky references to minutia of scholarship in vast and varied areas—from the Greco-Roman Classics that Wimsey quotes at will, as befits an educated gentleman of his generation, to the incunabula that Wimsey collects and loves so dearly. Yet all of this pedantry is presented in such a delightful tongue-in-cheek fashion that even a casual reader who will never, under threat of death, want to read a formal article on incunabula or Greek lyric poetry, would surely appreciate.

Peter Wimsey’s spectacular success freed Sayers financially to pursue the writing she really wanted to do—culminating with her translation of Dante, which she considered her best work. In this way, Wimsey was more of a journey, not the destination. He offered a starter intellectual home from which Sayers moved on to the abode of more serious, theological pursuits.

Still, all of Sayers’ writing, beginning with her Peter Wimsey novels, can be seen as a single body, conveying the following key truth. The joy of the intellectual life resides not just in absorbing ideas, being a lonely consumer. The true joy is, rather, communal: we want to share our ideas and findings with others. Recognizing that God created us all to love Him with all our mind (as well as heart, soul, and strength), we aim in the process to advance the intellectual life, both ours and that of our conversationalists and readers. Sayers most assuredly did all of this.

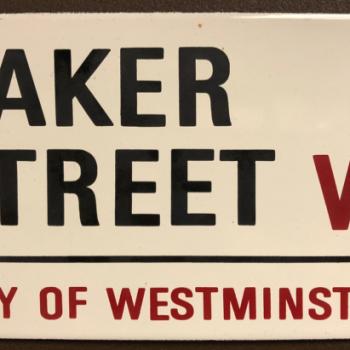

Image: Bronze statue of Dorothy L. Sayers by John Doubleday. Located on Newland Street, Witham, England. Source: Wikimedia Commons