Today’s guest post is by Christina J. Lambert. She is a doctoral student in English literature at Baylor University, studying the poetry and fiction of literary modernism. Her writing gives attention to questions of embodiment—discussing the ecological imagination, feminism, and sacramental theology within literature. Her writing has been published in Christianity & Literature, and she has forthcoming publications in Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature and Modern Fiction Studies.

In a season where we are met with story after story uncovering the abuse of women within Christian churches and organizations, we need voices who take the flourishing of the Church and of women seriously. Dorothy L. Sayers (1893–1957)—detective novelist, playwright, academic, and lay theologian—is just such a voice. And the fact that Sayers does not neatly fit within our contemporary categories makes her an even more poignant voice for a conversation that has become tragically polarized.

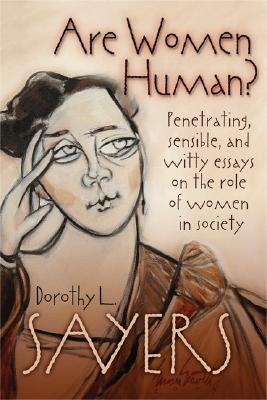

In Are Women Human?—her 1938 address to a women’s society—Sayers’s argument is simple: we need to treat women like ordinary human begins. Women aren’t particularly virtuous, or particularly evil; they aren’t particularly qualified or not. They are human beings—both unique and ordinary—each with distinctive desires and work to do, and they should be free to pursue that work.

In Are Women Human?—her 1938 address to a women’s society—Sayers’s argument is simple: we need to treat women like ordinary human begins. Women aren’t particularly virtuous, or particularly evil; they aren’t particularly qualified or not. They are human beings—both unique and ordinary—each with distinctive desires and work to do, and they should be free to pursue that work.

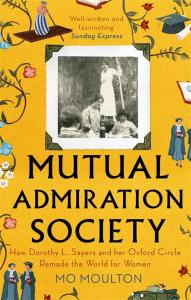

While Sayers’s advocacy for women is clear, the answer to the question of whether or not Sayers was a feminist depends entirely on whom you ask. For instance, in “A Writer and Theologian for Today,” Laura K. Simmons writes, “It is important to say… that Sayers did not consider herself a feminist, and likely would have bristled at being included in that movement.” However, in The Mutual Admiration Society (2019), Mo Moulton argues that Sayers “was not born a feminist; she became one” (103).

We might take Sayers at her word and wash our hands of the sticky debate:

… I replied—a little irritably, I am afraid—that I was not sure I wanted to ‘identify myself,’ as the phrase goes, with feminism, and that the time for ‘feminism,’ in the old-fashioned sense of the word, had gone past.[1]

Case closed, right? Except that Sayers’s biography, work, and writing push back against this statement and make the question of her feminism more complicated and, I’d argue, more fruitful than we’d imagine for understanding her life and influence.

Native to the “city of dreaming spires,” Dorothy L. Sayers was born in Oxford, England, in 1893. She attended Somerville College from 1912–1915 and was among the first women at Oxford to be awarded retroactive degrees in 1920. Mo Moulton tells the story of the girls Sayers met at Somerville College—girls who became the women who supported Sayers’s writing throughout her life and protected her legacy after her death. They called their writing group “The Mutual Admiration Society.” Sayers quipped, “If we didn’t give ourselves that title, the rest of College would.”[2] These women became midwives and magistrates, playwrights and historians—shaping the wide range of work Sayers saw women equipped and called to.

The Mutual Admiration Society encouraged and inspired Sayers’s famous detective novels, starring the charming Lord Peter Wimsey and the brilliant Harriet Vane. Sayers supported herself after college by working for advertising agencies—simultaneously writing novels and making money to pay for the upbringing of her son. Alongside of G.K. Chesterton and Agatha Christie, Sayers was a founding member of The Detection Club and was central to the revitalization of detective fiction in the twentieth century.

The Mutual Admiration Society encouraged and inspired Sayers’s famous detective novels, starring the charming Lord Peter Wimsey and the brilliant Harriet Vane. Sayers supported herself after college by working for advertising agencies—simultaneously writing novels and making money to pay for the upbringing of her son. Alongside of G.K. Chesterton and Agatha Christie, Sayers was a founding member of The Detection Club and was central to the revitalization of detective fiction in the twentieth century.

During her lifetime, she was known as a public intellectual who wrote plays for Canterbury Cathedral, published political and theological essays, and translated Dante’s Divine Comedy. By all accounts, her biography boasts accomplishments that might be easily defined as “trailblazing.” But, of course, there’s nothing Sayers would have detested more than for her life’s work to be categorized as accomplished for a “movement”: “we are too much inclined in these days to divide people into permanent categories, forgetting that a category only exists for its special purpose and must be forgotten as soon as that purpose is served.”[3]

Sayers reserves a great deal of criticism for women who copy the actions or habits of men when they are not good or useful for the woman imitating these actions. Trousers, she says, are practical and comfortable. Braces, or suspenders, are ugly and useless. We must always ask, is this a useful role or practice for women, or merely a means of “collaring the other fellow’s property?” Is it “trousers” or “braces”?[4] Sayers didn’t pursue her own work to make a point about the ability of women. She wrote novels and plays and essays because she believed it was the work she was called and equipped to do.

Yet, despite her protests of lack of involvement in the feminist movement, Sayers actively advocated for women’s right to wear trousers, so to speak, if they wanted to. In 1941, she wrote Maurice Reckitt and said, “I never was a ‘feminist’—I didn’t have to be—so I’m rather in the same semi-detached position as I am about everything else.”[5] Sayers dismissed the title of feminism, because—in her mind as a graduate of Oxford—she had access to the credentials she needed to do her work: “that’s why I said I had no need to be a feminist. But fifty years ago, there was still a real discrimination.”[6] She recognizes that her ability to distance herself from feminism is a result of the feminist work already done in her sphere. However, this distance would not prevent her from driving home her point to Reckitt about the “question of equality.”[7]

Yet, despite her protests of lack of involvement in the feminist movement, Sayers actively advocated for women’s right to wear trousers, so to speak, if they wanted to. In 1941, she wrote Maurice Reckitt and said, “I never was a ‘feminist’—I didn’t have to be—so I’m rather in the same semi-detached position as I am about everything else.”[5] Sayers dismissed the title of feminism, because—in her mind as a graduate of Oxford—she had access to the credentials she needed to do her work: “that’s why I said I had no need to be a feminist. But fifty years ago, there was still a real discrimination.”[6] She recognizes that her ability to distance herself from feminism is a result of the feminist work already done in her sphere. However, this distance would not prevent her from driving home her point to Reckitt about the “question of equality.”[7]

This letter to Reckitt would become her essay, “The Human-Not-Quite-Human,” now published alongside of “Are Women Human?” In both the letter and the essay, she makes the argument that true equality will never be realized until we stop universalizing the actions of men and gendering the actions of women. In a stunning, satirical section of “The Human-Not-Quite-Human,” she asks men to imagine what the world would look like if their lives were “unrelentingly assessed in terms of … maleness” (45). Imagine, she writes,

If from school and lecture-room, press and pulpit, he heard the persistent outpouring of a shrill and scolding voice, bidding him remember his biological function. If he were vexed by continual advice how to add a rough male touch to his typing, how to be learned without losing his masculine appeal, how to combine chemical research with seduction…

His newspaper would assign him with a “Men’s Corner,” telling him how, by the expenditure of a good deal of money and a couple of hours a day, he could attract the girls and retain his wife’s affection; and when he had succeeded in capturing a mate, his name would be taken from him, and society would present him with a special title to proclaim his achievement (56-58).

If humor is born of subverting expectations, then this imaginative index models wit and critique at its finest. The disjointedness of the images drives home the consequences of the double-standard we maintain for men and women. The images clarify that although Sayers had the legal rights necessary for her to do her work, she was still not exempt from a cultural environment that was, ultimately, dehumanizing for women.

Sayers extends these same criticisms throughout her fiction, but this particular essay concludes with a serious criticism of sexism within the Christian Church. Sayers declares that as far as culture is concerned, “Women are not human” (67). She adds this addendum: “God, of course, may have His own opinion, but the Church is reluctant to endorse it” (67). She begins another litany in this section of the essay. But this time, it is a series of images describing the attitude of Christ toward women:

A prophet and teacher who never nagged at them, never flattered or coaxed or patronized…who took their questions and arguments seriously; who never mapped out their sphere for them, never urged them to be feminine or jeered at them for being female; who had no axe to grind and no uneasy male dignity to defend; who took them as he found them and was completely unselfconscious (68).

Although Christ treated women as fully human, Sayers says that we did not see the same from “His contemporaries, and from His prophets before him, and from his Church to this day” (68). She closes her letter to Reckitt saying that the Church must address this question of inequality: “Indeed and indeed, the Church must pull her socks up and introduce a spot of reality into this controversy, for if she will not allow the equal possession of a common human nature, who will?”[8]

And so I wonder, what’s the word for someone who fights against sexism on a cultural level, in and outside of the Church? Can we acknowledge the similarities between Sayers’s intellectual advocacy and some of the work of feminist thinkers? Can we also be comfortable with their differences?

Sayers does not neatly fit within many of our categories, but she does make one thing clear: Christian scripture provides a picture of human flourishing that is unflinchingly at odds with a culture that abuses and dismisses women. Whether or not a Christian is comfortable putting the word “feminist” in their Twitter bio does not and should not determine their commitment to rooting out abuse within their church, workplace, and community.

I’ll close with what is, perhaps, the most fraught topic in Sayers’s criticism: her views on the ordination of women—a conversation which mainly depends upon one letter. In a letter to C.S. Lewis, we find Sayers saying she won’t weigh in against women’s ordination, because he would find her an “uneasy ally.” She writes, “I can never find any logical or strictly theological reason against it.” She won’t help Lewis build a case against women’s ordination, but she also has her reasons for not writing in support of it, as she does not want to “erect a barrier between us and the rest of Catholic Christendom” and to “break with Apostolic tradition.”[9] She couldn’t find a “reason against it,” but never, during her life, wrote in support of it. And that is the reality that those on both sides of this question must engage with.

As much as we might like to, we cannot make Dorothy L. Sayers someone that she is not.

No, we must take Sayers’s fierce advocacy for women alongside of her dismissal of feminist terminology. We should also acknowledge that “feminism” is not and never has been monolithic, and so this question also rests on a discussion of terms. I imagine Sayers would have all manner of thoughtful, biting criticism for all sides of our contemporary debates, which is precisely why she is a good voice for our time. She cannot be “used” for a cause; she must be treated, first and foremost, like a human being. And this practice alone—of treating men and women like the human beings they are—might help us transform our conversations, our conflicts, and our churches.

[1] Dorothy L. Sayers, Are Women Human? Astute and Witty Essays on the Role of Women in Society (Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co, 2005 (1971), 21.

[2] Moulton, The Mutual Admiration Society, 25.

[3] Sayers, Are Women Human?, 45.

[4] Ibid., 30.

[5] Sayers to Maurice Reckitt, July 12, 1941, The Letters of Dorothy L. Sayers, vol. 2 (Cambridge: The Dorothy L. Sayers Society Carole Green Publishing, 1997), 272.

[6] Ibid., 274.

[7] Ibid., 272.

[8] “Letter to Maurice Reckitt, 12 July 1941,” 275.

[9] Sayers to Lewis, July 19, 1948, The Letters of Dorothy L. Sayers, vol. 3, ed. Barbara Reynolds. A Noble Daring: 1944-1950, 3:3387-88.