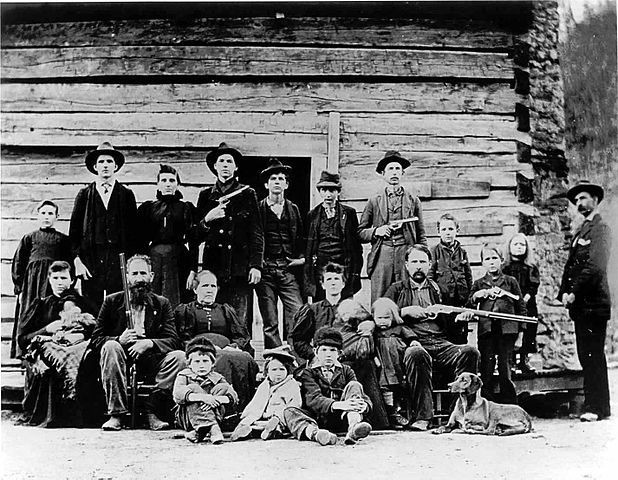

It’s Ash Wednesday, a day for repentance and sober reflection, launching the season of Lent. Retired literature professor that I am, I’m alert to imagery, so the day makes me think of ashes and literary portrayals of ashes. And on this day the children’s song and game always comes to mind:

Ring around the rosie,

A pocket full of posies.

Ashes! Ashes!

We all fall down!

I can still remember playing this in elementary school, us kids holding hands to form a circle, then running faster and faster in the ring to the point of everybody falling down with the last lines.

This song has since been somewhat spoiled by the claim that for all of its innocent cheer, it is really about dying from the plague. Supposedly, back in the Middle Ages when the plague stalked the earth and this song originated, one symptom of catching it was a red, “rosie” sore with a ring around it. People would carry around a “posie” of certain flowers in the mistaken hope that they would protect from the disease. Another symptom was sneezing. “Ashes! Ashes!” was actually something like “Atchoo! Atchoo!” And then, “we all fall down” dead.

I am happy to report that according to the Wikipedia article on the song, with the title of one of its variations “Ring a Ring o’ Roses,” the plague connection is almost certainly a “folk etymology,” an origin story that becomes popular but has no basis in fact. The entry gives multiple footnotes to folklore experts who give this reason why the plague interpretation isn’t true:

- The plague explanation did not appear until the mid-twentieth century.[19]

- The symptoms described do not fit especially well with the Great Plague.[31][36]

- The great variety of forms makes it unlikely that the modern form is the most ancient one, and the words on which the interpretation are based are not found in many of the earliest records of the rhyme (see above).[32][37]

- European and 19th-century versions of the rhyme suggest that this “fall” was not a literal falling down, but a curtsy or other form of bending movement that was common in other dramatic singing games.[38]

The third reason is the most telling. The song has many variations in many languages. Only American children sing “ring around the rosie.” British children sing “ring-a-ring o’ roses.” But the oldest versions lack all of those alleged plague references!

Not that folklore experts know what the silly lyrics mean, though there are various suggestions, some of which you can read about in the article. (In addition, I have heard that “the rosie” refers to the rosary, so that the song becomes a Catholic jingle about the devotional practice of praying using a circle of beads to keep track of the prayer cycle. I suspect that’ a folk etymology also.)

I do not believe that the song and game has anything to do with Ash Wednesday. I don’t want to start any other folk etymology. But it does conjure up a picture in my mind about this holiday.

We are running around in circles, not getting much of anywhere, but going faster and faster. That is, we are busier and busier, as we pursue the ever-repeating cycles of our jobs and vocations; the weeks, the months, and the years; the cycles of history. All of that seems futile to some people. Or, more positively, it is a game that we play.

Then “Ashes! Ashes!” The message of Ash Wednesday summons us out of our trivial preoccupations: “You are dust. And to dust you shall return.”

“We all fall down.” All of the cycles end, for us, when we die. And death should give us a perspective on our running around in circles, waking us up from our complacency, our pockets full of posies.

This is the message of Law and the wages of sin.

The cycle of the church year turns from the joy of Christmas and the light of Epiphany to the darker season of Lent, a time when we think about the state of our souls and our need for salvation.

Then comes Easter. After “we all fall down,” Jesus takes us by the hand and raises us back up, with Him.

Photo: Children playing Ring around the rosie, by Edwing Rosskam (1941) from U.S. Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Black & White Photographs http://www.loc.gov/rr/print/res/071_fsab.html via Picryl. Public Domain