You have got to read Edna Hong’s novel Bright Valley of Love, a true story about a community of profoundly disabled children, the Christians who cared for them, and a pastor who battled the Nazi euthanasia program to save their lives.

Although the book deals frankly with suffering and sadness, reading it is an overwhelmingly joyful experience. This is because the author accomplishes something very difficult to do in literature, conveying the joy that comes from the love of Christ as it spills over into love of neighbor.

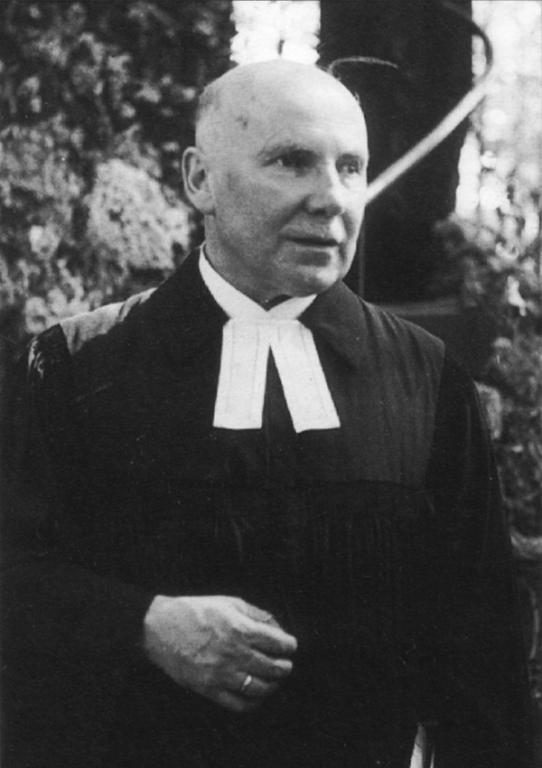

It tells the story of the Bethel Community, a Christian ministry in Germany devoted to the care of the physically and mentally impaired, led by Pastor Friedrich (“Fritz”) von Bodelschwingh. It does so through the point of view of one patient, Gunther, who can neither walk nor use his hands nor feed himself, a child abandoned by his parents and a cold-hearted grandmother who considered him “no good for anything.”

Then he came to Bethel. Most remarkable is the way the author shows Gunther gradually responding to the love shown him by the Deaconesses and his fellow patients, some of whom are in a worse condition than he is. Since he couldn’t speak, the staff first assumed that Gunther is also mentally impaired, but he isn’t. No one had ever talked to him in a way that would help him learn to talk. But he learns to speak, then to read, and when he goes to school his horizons keep expanding.

The pattern of regular worship “centers” him, for the first time in his life, and he learns more and more about Jesus, especially from Pastor Fritz, who has to be one of the most fully realized pastors in literature. Gunther finds that he has a talent for remembering hymns, which play an important part in the narrative and in addressing the spiritual issues that unfold. (I am told the audio version of the book, in which the hymns are sung, is especially effective.) Eventually, Gunther and his friends go through confirmation class, after which they enter a “calling” in the community, leading to thoughtful and perceptive reflections on vocation, on how they can serve God and their neighbors despite their conditions.

Meanwhile, what happens in the outside world impinges on the Bethel community. The economy collapses, inflation soars, Bethel takes in the unemployed and homeless, and soon the Nazis come into power. Whereupon they launch their euthanasia program, attempting to breed the master race and to eliminate the unfit and “useless.” They send a green questionnaire to hospitals and treatment centers to identify candidates for extermination. Bethel refuses to co-operate. As the news of what is happening goes through the community, Pastor Fritz stands up to the Nazis and does what he can to protect his flock.

Though the novel itself only hints at this, Pastor Fritz would go on to become a leader in the Confessing Church movement, along with Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Martin Niemöller, and Hermann Sasse, among others. The Bethel Confession, which opposed the Nazified “German Christian” movement that had taken over the established church, emerged out of this Bethel.

The story is gripping, immersive, and exciting. And very moving. I warn you: I don’t care how cynical you are–it will bring tears to your eyes. Good tears.

Edna Hong, who died in 2007, was a National Book Award winning translator. She learned about Bethel, which is still operating, from a POW–a Lutheran pastor–her husband met after the war. She came to know Gunther, who by this time was 62, first hand. She first published the book in 1979. Unaccountably, it fell out of print and into obscurity. But Concordia Theological Seminary Press has done a great service in bringing it back.

The book deserves wide readership, now more than ever.

Today Christianity is widely misunderstood, twisted, and repudiated. This book shows the Gospel of Christ and its impact on people’s lives in a powerfully winning way.

Today the church is discredited. The Bethel Community shows what the church can be at its best.

Today churches are being encouraged to engage in works of mercy. This book shows what that looks like and the price it can cost.

Today, the overturning of the Roe v. Wade decision has sparked a backlash against the pro-life cause. This book makes the case for the value of all human life, no matter how unwanted, and it does so not just with argumentation but with an imaginative appeal that pierces the heart. (In the Epilogue, the author explicitly connects the struggle against euthanasia to the struggle against abortion.)

Today, we Lutherans still face the stigma of Hitler’s Germany, how so many so-called Lutherans fell into line with Nazism and its atrocities. We need to distance ourselves from that legacy by aligning ourselves with the confessing Lutherans, making a clear distinction from the culture-conforming, theologically liberal “German Christian” movement, with its project of purging Christianity of its “Jewish”–i.e., Biblical–elements, to the point of removing the Old Testament from the Bible. (See my book on this subject.)

Also, in purely literary terms and as an exemplar of Christian artistry, Edna Hong knew how to write. Here is the opening of the novel:

In the world of his mother’s womb, the fluid of life that trickled into him through his umbilical cord was weak and starved. The world into which he was born one day in the year 1914 nourished him no better. Perhaps even worse. For it was the worst of times, and his mother was not the best of mothers. And his father went off to World War I, which the whole world lost, although some countries thought that they had won it. For the baby boy Gunther, who was born in Germany–the country that lost the war most hurtfully–the sum of all these things was a lifetime as a cripple.

“No good for anything,” said his grandmother coldly when the war was all over and his father rescued him from the woman who was not the best of mothers and brought him to her own house in a great gray, dingy city west of the Rhine, north of the Ruhr, and south of the Lippe rivers.

The grandmother had swept and scrubbed floors and rubbed clothes on a washboard practically every day she could remember of her life, and she believed that only people who did something useful like that had any right whatsoever to live in the world. Or people who were rich enough not to have to be useful. (pp. 9-10)

Here is a passage from much later in the story, when Gunther and his epileptic friend Klaus–both of whom know that they would be put on the death list–role play the conversation that they think Pastor Fritz may be having at that very moment with Dr. Karl Brandt, Hitler’s physician and the head of the euthanasia program, who came to Bethel to arrange for the turning over of its patients:

“According to you, Dr. Brandt, there are people who are non-human. Your standard is supposed to separate humans from non-humans, and the non-humans are to die. Would you call that a human standard?”

“Yes, for I do not call the lives these poor creatures live human.”

“Where is the dividing line? When does a human life become non-human?”

“When it cannot respond to another human being in a human way. When it is not able to have human association with anybody.”

“Dr. Brandt!” Gunther’s voice rang with triumph. “That cannot be said of even the weakest in mind and body here in Bethel. I must say that I have never in my life met such a person, and I have spent my whole life here in Bethel. if you were to say that of anyone here in Bethel, I’m afraid I would have to ask you, Dr. Brandt, if you are capable of human association with another human.”

“Bravo, Gunther! Bravo!”. . . .

“Therefore, Dr. Brandt, no rulers on earth can make a standard that decides what is human, what human life is worth preserving, what human life is not worth preserving. God alone can give us that standard. And he has done so, Dr. Brandt. The answer to the question about the worth of human life is Jesus Christ. First of all he became human. And in his life here on earth, whom did Jesus Christ place first in his love and concern? Tell me that, Dr. Brandt!”

“I prefer to remain silent before that question, Pastor von Bodelschwingh.”

“Dr. Brandt, before the answer to that question all of us have to be silent. The poor, the wretched, the helpless, the lonely, the sick, the crippled, the epileptics–that was Christ’s standard here on earth. It is his standard today. It is the standard we live by here in Bethel. We can allow no other standard that God’s here, for here in Bethel God rules!” (pp. 150-151)

See what I mean?

Finally, for further impressions of the book, read these reviews by Cheryl Magness in The Federalist , Anthony Dodgers in Gottesdienst, and Mary Moerbe in Meet, Write, and Salutary.

HT: Paul Grime

Photo: Rev. Friedrich von Bodelschwingh by Unknown author – Scan: Ersttagsbrief 50. Todestag Friedrich von Bodelschwingh (1996), Deutsche Post AG, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=76134920