To show the relevance of Johann Georg Hamann (1730-1788) today, he may have been the first, in 1784, to add to an unrelated word the prefix “meta.”

In his day, he had an impact on thinkers ranging from Goethe to Kierkegaard to C. F. W. Walther. Today he has been rediscovered and is credited with anticipating–and critiquing–both modernism and postmodernism. Notre Dame professor John Betz sees in Hamann’s thought the only way forward from postmodern nihilism, opening the door to a “post-secular” vision.

Hamann also was a devoted Christian, whose cutting-edge philosophy was largely a sophisticated application of his confessional Lutheran theology.

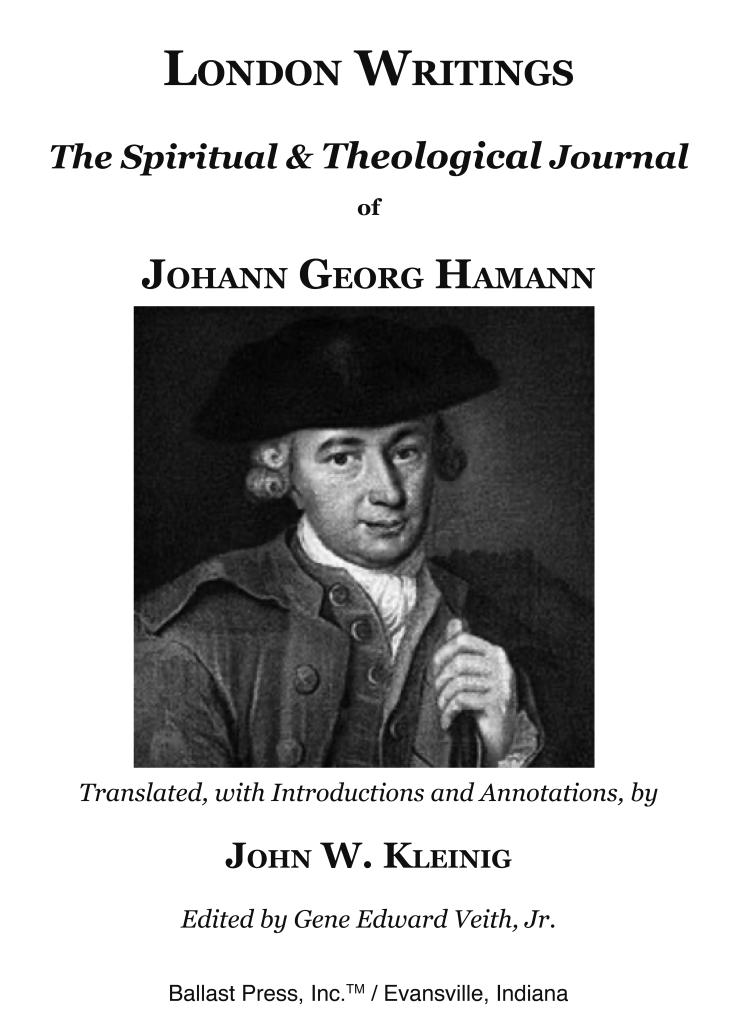

Unfortunately, not all of Hamann’s writings–which are notoriously challenging to read, due to his playful multi-leveled style–are available in English. But now Hamann’s most foundational work, the London Writings–in which he tells of his conversion to Christianity, meditates on Scripture, and formulates the ideas he would develop throughout his life, doing so in a clear, engaging style–has been translated in its entirely into English.

And the translator is John W. Kleinig, the Australian theologian known to many of us Lutherans in the U.S. as the author of books like Grace upon Grace and Wonderfully Made and for his work with the Doxology ministry. I was privileged to work on this project with him.

Hamann was part of a circle of young Enlightenment rationalists, including Kant. The father of one of them in Riga hired the 28-year-old Hamann to go to London to arrange some business negotiations. But his mission was a failure, Hamann fell in with dissolute company, and he was soon destitute. At this low point in his life, he picked up an English Bible and started to read it. The Law and the Gospel had their full effect on this bright but troubled young man, and he was transformed into a fervent follower of Christ and a rapturous lover of Scripture.

The “London Writings” were written during this period in the midst of his spiritual awakening, which also proved to be a catalyst for ideas about the physical world, language, reason, and faith that he would develop for the rest of his life. They consist of nine works:

(1) “On the Interpretation of Sacred Scriptures.” A brief summary, with statements like this: “The inspiration of this book is as great an act of self-effacement and condescension as the creation of the world by the Father and the incarnation of the Son.”

(2) “Biblical Meditations of a Christian.” Hamann’s notes as he read the Bible from beginning to end, amounting to a Christo-centric Bible commentary that is electric with unexpected insights.

(3) “Thoughts on the Course of My Life.” The account of his life and his dramatic conversion.

(4) “Thoughts on Church Hymns.” Hamann would later say that his spiritual life centers in the Bible, Luther’s Small Catechism, and his church’s hymnal. Here he meditates on the lyrics of classic hymns, some of which we still sing today, culminating in his own ecstatic joy in the Ascension of Christ and in our union with Him.

(5) “Deuteronomy 30:11-14 together with Romans 10:4-10.” Tying together two texts that say, “the word is very near you. It is in your mouth and in your heart.” Thoughts on connection between the Word and Faith.

(6) “Fragments.” Our thoughts, Hamann says, are fragments, which we must gather together into baskets, as the Disciples did after the feeding of the 5,000. A collection of brief thoughts on a variety of topics, some of which Hamann would continue to develop.

(7) “Meditations on Newton’s Essay on Prophecies.” Not Isaac Newton the scientist, nor John Newton the hymn writer, but Thomas Newton the Anglican theologian. Here Hamann writes about the Holy Spirit.

(8) “Further Thoughts on the Course of My Life.” Hamann picks up his life story after he leaves London and goes back home. We see how his rationally Enlightened friends now reject him and trace the course of his ill-fated courtship of Katherina Berens.

(9) “Prayer.” A wide-ranging prayer that Hamann would continue to use in his morning and evening devotions.

This translation with commissioned in 2017 by George Strieter of Ballast Press, a micropublisher that reprinted Gustaf Wingren’s Luther on Vocation and Adolf Koeberle’s Quest for Holiness, both of which were taken over by Wipf & Stock. George had read about Hamann in Oswald Bayer’s book about him, which did much to facilitate his rediscovery. He told me about Hamann, and then Dr. Kleinig put me onto Betz’s book, probably the best introduction to his thought. George had the idea to translate the London Writings, and together we persuaded Dr. Kleinig, who is fluent in German, to take on this enormous project. Not only did he do the translation, he also provided extensive introductions to each section, footnotes, and references to Hamann’s Biblical allusions.

I edited the translation. That means, at first, I worked with Dr. Kleinig as his reader, going over his renditions, discussing with him how to express certain passages, and making the occasional suggestion. Once the manuscript was finally finished, a process that took two years, my editorial duties shifted to the publishing side, setting the book into type, requiring me to learn InDesign publishing software–which, believe me, was not easy–and then preparing the exhaustive topical index and Scriptural index. This was my big project during the pandemic lockdowns! Then George and I had to see the project through the printing process, which proved to be a difficult and time-consuming task in itself.

Now, four years later, London Writings: The Spiritual & Theological Journal of Johann Georg Hamann, is finally completed and available to all!

You can buy it at the website, which includes other information you might want to look at, or via Amazon. I urge you to buy it, urge any libraries you are connected with to buy it, and otherwise spread the word.

This book can be a game-changer for contemporary theology, putting it back on a Biblical, Christ-centered track, and for those attempting to find a way past the dead ends of postmodernism. But reading this book is also profoundly devotional. It rekindled for me the joy of reading and studying God’s Word.

I’ll have other posts over the next few days that will focus on some of the content of the London Writings to show you what I mean.