I first heard the phrase from a radical feminist: If God punished His Son for our sins, that would be “cosmic child abuse.” Since then, I have been hearing it more and more, including from evangelicals! But to think of the atonement in that way demonstrates a profound misunderstanding of the triune God and the deity of Christ.

Here are some comments from Rev. Steve Chalke, a Baptist and a leader of the U.K.’s progressive evangelicals. From Christian Today,Traditional view of atonement ‘cheapens God’s forgiveness’ says Steve Chalke:

Chalke, who leads Oasis Church Waterloo as well as heading up the community change charity, has previously described the doctrine – assumed by many evangelicals – that God punished Jesus on the cross instead of us as ‘cosmic child abuse’.

In his latest video, he says PSA removes God’s ability to forgive.

He says: ‘Why can’t God do what he asks us to be able to do; to freely forgive without demanding punishment first?’. . . .

“If God needs someone to “pay the price” for our sin, the question is does he ever really forgive anyone at all? Stop and think about it for a moment. If you owed someone a hundred pounds and they held you to it – refused to release you from the debt – unless or until someone else paid your bill for you, in what sense did they forgive your debt at all?’

Note the anthropomorphizing of God: Why doesn’t He do what we are supposed to do? But what if God is not a kind person like us looking down from the sky, but a being who is qualitatively different than we are, completely “other” than ourselves? What if God does not just hand down rules for our and His behavior, but rather, is the source of everything that is good, underlying the very fabric of the moral order? So that when we violate that moral order, we are in conflict with God and our very creation, to our ruination? And what if, this God, unfathomably, as part of this same goodness that we violate, loves us anyway? And that He resolves this contradiction by becoming one of us and, somehow, taking into Himself our sins and their consequences, imparting to us His goodness in exchange?

God does not punish a random human being for the sins of the world. Nor does He punish a merely human offspring. The Son of God is the Second Person of the Trinity. In the words of the definitive Athanasian Creed,

The Godhead of the Father, of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost, is all one; the Glory equal, the Majesty coeternal. . . .And in this Trinity none is before, or after another; none is greater, or less than another. But the whole three Persons are coeternal, and coequal. . . .Our Lord Jesus Christ, the Son of God, is God and Man; God, of the Substance [Essence] of the Father; begotten before the worlds; and Man, of the Substance [Essence] of his Mother, born in the world. Perfect God; and perfect Man.

God substituted Himself for us. God suffered for us. God sacrificed Himself for us, leaving us the command to sacrifice ourselves for our neighbors in our crosses and vocations.

We experience this redemption as forgiveness. But, from God’s side, this is something far more than what we do in telling someone “no worries” when we forgive a slight. God gives us satisfaction for our sins. He gives us remission of our sins.

I can see someone not believing this or offering some alternative explanation. But to deride this teaching and to describe this incomprehensible act of infinite love as evil strikes me as monstrous.

And, no, contrary to what Rev. Chalke thinks, the doctrine of substitutionary atonement did not originate with John Calvin. You can find it, among other places in the Bible, in Isaiah:

Surely he has borne our griefs

and carried our sorrows;

yet we esteemed him stricken,

smitten by God, and afflicted.

5 But he was pierced for our transgressions;

he was crushed for our iniquities;

upon him was the chastisement that brought us peace,

and with his wounds we are healed.

6 All we like sheep have gone astray;

we have turned—every one—to his own way;

and the Lord has laid on him

the iniquity of us all. (Isaiah 53:4-6)

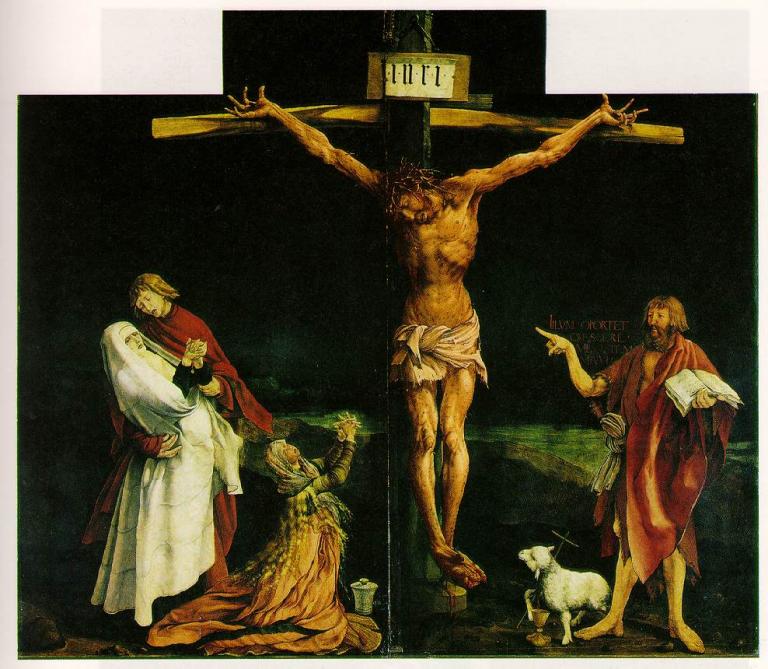

Illustration: Matthias Grünewald (d. 1528), “The Crucifixion” via Fortinbras at nl.wikipedia [Public domain], from Wikimedia Commons