Even secularists today are talking about the importance of having a sense of “calling”; that is, a sense of vocation (a Latinate word that means, simply, “calling”). Many secularist treatments seem to be oblivious to the fact that this is a theological concept and that, strictly speaking, you cannot have a “calling” apart from Someone who “calls” you. Nevertheless, this interest in vocation is a good sign, demonstrating that churches would do well to recover and to teach the doctrine of vocation, which is a subject of urgent interest to people today, both inside and outside the church.

Furthermore, the doctrine of vocation teaches that while non-believers do not know the Caller–so that their work is not the fruit of their faith, as it can be for Christians–God nevertheless does work through non-believers as well.

I have written quite a bit about vocation. To review, vocation is not just about how we make a living. Rather, we have multiple vocations in the “estates” that God has designed for human life: the family, the society, and the church. Also the workplace, which might be an aspect of any of those estates. God providentially works through human beings in their vocations to give His gifts: He provides daily bread through farmers, bakers, and shopkeepers; He creates new life by means of fathers and mothers; He protects us by means of lawful authorities; He proclaims His Word by means of pastors, etc., etc. And the purpose of every vocation is to love and serve one’s neighbors.

I stumbled across an article in Aeon that summarizes psychological research on “finding your true calling.” This is not the theological understanding of calling. For one thing, it restricts the discussion to the workplace. And instead of focusing on loving and serving the neighbors whom your calling brings to you to love and to serve, it is more about self-fulfillment, which is NOT what Christian vocation is all about. So though it misses the main points about “calling,” I found it interesting nonetheless. It can help us see some other misconceptions about vocation. And it illuminates, from a secular point of view, some other aspects of our callings and how we should think about them.

I’ll give the five points it raises and comment about each one. (Go to the link, which tells about the research in each of these areas.) From Christian Jarrett, Psychology’s five revelations for finding your true calling:

(1) “First, there’s a difference between having a harmonious passion and an obsessive passion.”

The article uses the language of having a “passion” for your work. “Passion” used to be a negative word, evoking strong emotions that need to be curbed. But in this sense it refers to a certain zeal or enthusiasm (which used to be another bad word) for your work. But we hear this a lot, as in, “you need to have a passion for what you are doing.”

The research has found two different kinds of passion in this sense. An “obsessive passion” is an all-consuming pre-occupation with your work or what you are trying to accomplish. That kind of passion leads mainly to stress, lack of control, and burn-out. “Harmonious passion,” though, involves a sense of control and harmony with other facets of your life. This kind does result in better work performance and over-all vitality.

(2) “Secondly, having an unanswered calling in life is worse than having no calling at all.”

This says that if you have a sense of calling to do something, but it is “unanswered”–that is, you aren’t doing it–this creates dissatisfaction with what you are doing, as well as other kinds of frustration and unhappiness. This is in contrast to the Christian understanding that vocation is in the here and now, that God has called you to this moment and this task where He has placed you. (See #4 below.)

(3) “The third finding to bear in mind is that, without passion, grit is ‘merely a grind’. “

Experts have been referring to “grit”; that is, perseverance and toughness. Such “grit” is important to effectiveness at any kind of work. The psychological research cited here has found that you need “grit” along with “passion.” If you just have grit, but no passion for what you are doing, you will only experience drudgery. While if you have passion but no grit, you will get little done.

The doctrine of vocation does include “bearing the cross” in vocation, the trials and tribulations that your vocation will bring upon you, the difficulties and failures involved in loving and serving your neighbor. Yes, indeed, we must persevere in our callings (for example, marriage), even when it isn’t easy. But bearing our own crosses and realizing how they are taken up into Christ’s cross as we depend on Him builds up our faith and contributes to our sanctification.

(4) Another finding is that, when you invest enough effort, you might find that your work becomes your passion.

This is an important finding. If you don’t have “passion” for the work you have to do, if you devote yourself and put in the effort, you can develop the passion. The passion doesn’t necessarily come first.

This is more constructive than some of the other findings. It fits in more with the teaching that your calling is in the here and now. Your attitude–particularly, for a Christian, acting in faith, with a realization that God is present, even in this boring job or this frustrating relationship–can transfigure how you see that calling and how you experience it.

(5) “Finally, if you think that passion comes from doing a job you enjoy, you’re likely to be disappointed.” Instead, the beneficial, satisfying passion comes “from doing what you believe in or value in life.”

This is extraordinarily important and deals with a misconception that Christians too often have. Your calling is not measured by how much you enjoy what you are doing. In secular terms, your “passion” is not the same as enjoyment. If you aren’t getting pleasure from your job, or your family, or your church, that doesn’t mean they aren’t part of your calling. Rather, the good kind of “harmonious” passion comes from doing what is right, knowing that your work has a purpose that you are committed to. For a Christian, that means loving and serving your neighbor. Such a purpose can give your work, your relationships, your responsibilities, your offices, a meaning and a “passion” that can make all the difference.

If you are interested in vocation, you might want to check out my “trilogy” on the subject:

God at Work: Your Christian Vocation in All of Life,

with Mary Moerbe, Family Vocation: God’s Calling in Marriage, Parenting, and Childhood

Working for Our Neighbor: A Lutheran Primer on Vocation, Economics, and Ordinary Life

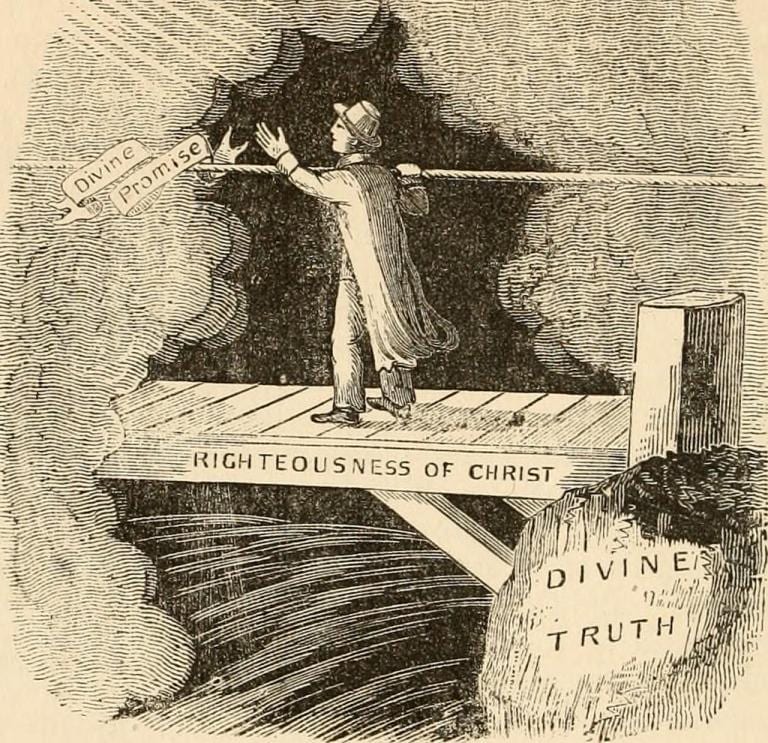

Illustration by lsucc via Pixabay, Creative Commons