I’ve been reading a ground-breaking new book in the field of the sociology of religion (more on that later), which put me onto the work of Yale social scientist Sigrun Kahl. She has studied the attitudes towards the poor in the Catholic, Lutheran, and Reformed traditions. She then shows the connection between those theological positions and the way nations influenced by those traditions deal with the poor to this very day.

I’ll summarize her research, while adding my own thoughts.

Catholics

Catholics tend to exalt the poor, considering them to be morally and spiritually superior. (Listen to Pope Francis when he talks about the poor, which he does in nearly every pronouncement.) After all, the poor are unencumbered by the material possessions that are the obsession of this world. Also, they suffer, thus practicing the discipline of asceticism, which brings them closer to God.

In the Middle Ages, one of the most practiced “good works” necessary for salvation was almsgiving, so that for the more affluent, the poor became, in effect, a means of salvation. Begging was encouraged and rewarding.

The Catholic respect for the poor manifested itself in the practice of voluntary poverty. Those wishing to pursue the highest spiritual life by becoming a monk, nun, or a priest take a vow of poverty.

Ironically, according to Kahl, the governments of Catholic nations–such as Italy, Spain, France, and she might have added the countries of Latin America–tend to be “ungenerous” in helping the poor. This is seen as the task of the church and of pious individuals, not the government.

There are relief efforts, including from the governments, that feed the hungry and take care of poor people’s basic needs. But this is still the equivalent of almsgiving. The poor remain poor. This is because being poor is seen as a good thing.

Reformed

In stark contrast to the view of Catholics, the Reformed tend to stigmatize the poor. Poverty is due to sin. The poor bring their poverty onto themselves by their irresponsible behavior, profligate ways, sexual transgressions, substance abuse, and laziness.

Kahl draws on Max Weber, who maintained that Calvinists viewed prosperity as a sign of their election. Conversely, she says, poverty can be a sign of reprobation. (I have questioned Weber’s thesis and whether Calvinists did, in fact, believe in these things.)

There is, however, a category of the “deserving poor,” who are in poverty through no fault of their own. They are worthy of help, and helping them is a “good work.”

Reformed Christians did and do help the poor, with a good dose of evangelism so that they can be freed of their poverty-causing sin.

In Reformed-influenced nations–such as the United States, Great Britain, and the Netherlands–the stigma of poverty remains. Kahl cites the early workhouses in Great Britain, which were purposefully harsh with horrendous condition so that poor people would not want to go there, an effort, in effect, to punish the poor. As in Catholic countries, helping the poor tends to be seen as tasks for the church and individuals–manifested in various “Christian ministries”–though the governments somewhat grudgingly operate “welfare” programs.

Kahl says anti-poverty programs in the USA, UK, and the Netherlands are thus highly fragmented and non-systematic.

I would add that the stigma attached to poverty in these countries is, for many of the poor, a powerful incentive to escape it. Many American poor people feel shame that they have had to “go on welfare,” and they become highly motivated to “get off welfare,” which restores their self-esteem.

Lutheran

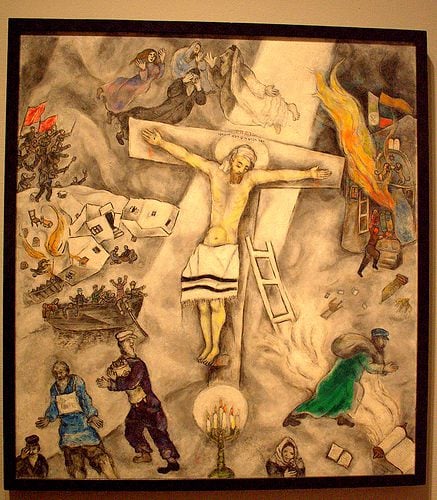

For Lutherans, the poor are sinful, but so are the rich and middle class; and they have all been redeemed by the blood of Christ. The Lutherans approached the poor in terms of vocation.

All vocations are equal before God and so are all worthy of respect. God gives daily bread to all by means of the poor peasant hard at work in the fields, who can thus live out his faith by loving and serving his neighbors. But begging is anathema! And those who are poor because they have no work must find a vocation!

Thus, in Lutheran-influenced nations–especially the Scandinavian countries of Denmark, Sweden, Norway, and Finland, and also Germany (though Kahl says the German approach is also influenced by its large Catholic population)–the emphasis is on ensuring that the poor work.

These so-called “welfare states” have strong work requirements. These are bolstered by programs to actually help the poor find employment. (Germany also incorporates the principle of “subsidiarity” associated with Catholicism, meaning that institutions than the government also play a role. If a poor person’s extended family can help, they must do so, and the government will give the person in need no payments. I would say that this approach also rests on vocation, since family is also vocation.)

With the doctrine of the Two Kingdoms, the church takes care of people’s spiritual needs, while the state takes care of their temporal needs. Thus, the Lutheran churches turned over the task of dealing with the poor to the state, which developed systematic programs to alleviate poverty by ensuring that the poor have vocations.

The goal is for the poor person to no longer be poor!

And, indeed, the Lutheran countries have far less poverty than the Catholic or Reformed countries do.

To be sure, there are other factors at work in those outcomes. Scandinavian countries are more culturally–and religiously– homogeneous than the United States and Great Britain.

But it’s interesting that even in these ostensibly “secularist” nations, the religious influence is still operative. And the Scandinavians know it, as Kahl makes clear:

When asked why work is so important in Swedish poverty policy, an interviewee in the Public Employment Service smiled and replied with a proverb: ‘‘We Swedes have Luther sitting on our shoulders’’ (p. 94).

Photo by Steve Depolo, Charity Box for the Poor, Basilica of St. Adelbert, Grand Rapids via Flickr, Creative Commons License