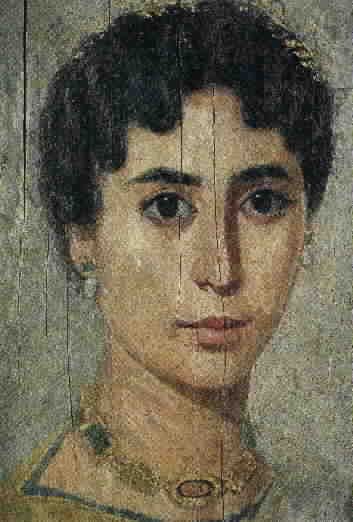

NeoPlatonist pagan philosopher Hypatia of Alexandria (355-415 AD) was the Susan Sontag of her time.

Like Sontag (1933-2004), the late renowned modern American philosopher and writer whose broad streak of white through a black mane gave her an emphatic look, the Greek philosopher Hypatia was purported to be uniquely beautiful and charismatic, intellectually brilliant and well-regarded among the elite in Alexandria in the late 4th and early 5th century AD.

Sadly, these laudable qualities ultimately led to her destruction.

Thomas Little Heath, a 20th century British mathematician and classical scholar, wrote in A History of Greek Mathematics in 1921 that Hypatia, “… by her eloquence and authority … attained such influence that Christianity considered itself threatened.”

By all accounts, Hypatia was a woman of profound substance in sumptuous Alexandria, the sparkling urban gem of antiquity founded by Alexander the Great, one of a number of cities the prolific conquerer created and gave his name. Hypatia’s fame emanates from her status as a philosopher of some genius, and from her appalling murder — a well-documented flaying and mutilation at the hands of a frenzied Christian mob.

The daughter of Greek mathematician Theon Alexandricus, Hypatia was born and educated in Athens. In 400 AD, she became head of Alexandria’s Platonist school, where she taught the philosophies of Plato and Aristotle to her pupils, who included pagans, Christians and foreigners of various persuasions. Among her professional achievements, she assisted her father in his 11-part commentary, in Greek, on Claudius Ptolemy’s Almagest, a treatise on mathematics and astronomy. She also helped her father update Euclid’s classic Elements, which became the basis for all subsequent editions of that influential masterwork.

Enemy of superstition

None of Hypatia’s written work remains extant except for references to it, and she was said by some scholars to be an excellent editor and conservator of previously published mathematical works. Quotes attributed to her reveal a practical, nonsuperstitious mind and prescient wisdom:

“To teach superstitions as truths is a most terrible thing. The child mind accepts and believes them, and only through great pain and perhaps tragedy can he be in after years relieved of them.”

“All formal dogmatic religions are fallacious and must never be accepted by self-respecting persons as final.”

“Truth does not change because it is, or is not, believed by a majority of the people.”

You can see a problem for the female philosopher in a deeply paternalistic society where Christianity was ascendant and growing more violently coercive by the day.

Hypatia reportedly was a Neoplatonist, an aficionado of the mathematical practices of Plato’s Academy in Athens and a proponent of the philosophy of 3rd century thinker Plotinus, who, like many Platonists and unlike Aristotle, had a visceral distrust of materiality, favoring logic and mathematics over empirical investigation and analysis, and law over nature. Plotinus believed the ultimate goal of human existence was mystical union with the divine, not empirical study of material reality — a hint of the Christian mystical impulses to come.

However, as her purported quotes imply, Hypatia was also a clear-eyed realist, and there is evidence that her students idolized her. Significantly, she was a woman of unquestionable prestige — widely known to be broadly accomplished and one of the city’s most visible public figures among the intellectual elite — at a time when Greek women were mostly invisible in society, and generally viewed, at best, as breeders or pleasure vessels.

Socrates Scholasticus, a contemporary Christian historiographer described Hypatia in is Ecclesiastical History:

“There was a woman at Alexandria named Hypatia, daughter of the philosopher Theon, who made such attainments in literature and science, as to far surpass all the philosophers of her own time. Having succeeded to the school of Plato and Plotinus, she explained the principles of philosophy to her auditors, many of whom came from a distance to receive her instructions. On account of the self-possession and ease of manner which she had acquired in consequence of the cultivation of her mind, she not infrequently appeared in public in the presence of the magistrates. Neither did she feel abashed in going to an assembly of men. For all men on account of her extraordinary dignity and virtue admired her the more.”

A woman of substance

Hypatia’s charismatic influence as one of the “scholars in residence” at Alexandria’s renowned Museum, a world-beating university housing civilization’s pre-eminent library of the day, is powerfully evoked in this passage from Chapter Four of Stephen Greenblatt’s The Swerve:

Such was her authority that other philosophers wrote to her and anxiously solicited her approval. “If you decree that I ought to publish my book,” wrote one correspondent to Hypatia, “I will dedicate it to orators and philosophers together.” If, on the other hand, “it does not seem to you worthy,” the letter continues, “a close and profound darkness will overshadow it, and mankind will never hear it mentioned.”

Yet, despite her renown and ability to move easily among Alexandria’s movers and shakers, she apparently tended not to meddle in politics, according to Greenblatt. But, most unfortunately for her, not always.

Pagan Hypatia’s fate was sealed by a convergence of dangerous themes: her chumminess with the ruling elite; the fact that a beautiful woman who embodied such intellectual power and prestige was viscerally abhorrent to Alexandria’s traditionally chauvinistic, misogynistic masses; alarming and violent religious discord was roiling in the city at the time; and growing Christian temporal power in the city that was becoming ever more aggressive toward pagans such as Hypatia, and Jews.

Roman Emperor Constantine II had started the ball rolling in the early 4th century by first allowing Christianity to exist throughout the Roman Empire, converting himself to the faith, then making it the official creed of his realm. His zealous successor, Theodosius the Great, in 391 targeted for destruction paganism — the Greek and Roman polytheistic religious systems — unleashing Christians to insult and intimidate non-Christians in the streets of Alexandria and elsewhere. Alexandria’s Christian patriarch one year deputized a horde of monks, joined by other Christians, to destroy the temple honoring the Graeco-Egyptian god Serapis in the Museum complex, replacing pagan idols with Christian relics in the Serapeon buildings. After this assault, the pagan poet Palladas expressed the growing despair of the city’s Hellenistic citizens:

Is it not true that we are dead, and living only in appearance,

We Hellenes, fallen on disaster,

Likening life to a dream, since we remain alive while

Our way of life is dead and gone?

“An early manifestation of Alexandria’s contentious religious environment at the time was the razing of the Serapeum, the temple of the Greco-Egyptian god Serapis, by Theophilus, Alexandria’s bishop until his death in 412 CE,” wrote Australian mathematician and writer Michale A.B. Deakin in Hypatia of Alexandria. “This event was perhaps the final end of the great Library of Alexandria, since the Serapeum may have contained some of the Library’s books. Theophilus, however, was friendly with Synesius, an ardent admirer and pupil of Hypatia, so she was not herself affected by this development but was permitted to pursue her intellectual endeavours unimpeded.”

Christian aggressions

By 415 AD, Jews and pagans were being seriously pushed around in Alexandria, and, enraged, many fought back, which only exacerbated the dangers.

In March of that year, the city’s Christian patriarch, Cyril, nephew of predecessor Theophilus, who had ordered the temple destruction, expanded attacks and persecutions against Jews and pagans. After Christian-Jewish violence broke out, Cyril, enlisting hundreds of monks as henchmen to bolster already raucous Christian street mobs, demanded that the city’s entire Jewish population be expelled. Alexandria’s administrative governor Orestes, a moderate Christian, refused, and was supported by the city’s pagan intellectual elite, including its most distinguished ambassador, Hypatia.

Vicious rumors

Rumors purportedly began circulating in the city, implying that interest by a woman in obscure scientific pursuits was so strange and unnatural that Hypatia must be a witch who practiced black magic. Ironically, as a follower of Plotinus, she was probably more spiritual and “god-ly” than her enemies could have guessed. It didn’t matter. Returning to her house in a carriage one night, she encountered a frenzied Christian mob and was doomed, as recorded by Socrates Scholasticus, a contemporary of Hypatia’s, in his Ecclesiastical History:

Yet even she fell a victim to the political jealousy which at that time prevailed. For as she had frequent interviews with Orestes, it was calumniously reported among the Christian populace that it was she who prevented Orestes from being reconciled to the bishop. Some of them, therefore, hurried away by a fierce and bigoted zeal, whose ringleader was a reader named Peter, waylaid her returning home and, dragging her from her carriage, they took her to the church called Caesareum, where they completely stripped her, and then murdered her with tiles. After tearing her body in pieces, they took her mangled limbs to a place called Cinaron, and there burnt them.

According to Greenblatt in The Swerve, the death of the graceful philosopher was a catastrophe for everyone for all time:

“The murder of Hypatia signified more than the end of one remarkable person;” he wrote, “it effectively marked the downfall of Alexandrian intellectual life and was the death knell for the whole intellectual tradition that underlay the text that Poggio recovered [Lucretius’ On the Nature of Things] so many centuries later.”

Materialist philosophy nearly died with Hypatia, in other words.

Years before this devastating disappearance of ancient learning in the Western world (and to some extent in the East), which only fate saved from being permanent, Hypatia clearly saw the potential power of knowledge on human existence.

“He who influences the thought of his times, influences all the times that follow,” she once reportedly wrote. “He has made his impression on eternity.”

Please sign-up for new-post notifications (aboove right). Sharing, comments much appreciated!