WILLS POINT, TX – Gospel for Asia (GFA World) and affiliates Gospel for Asia Canada, founded by KP Yohannan issued the first part of a Special Report update authored by Karen Mains on the chilling reality of missing and murdered indigenous women in North America.

In my previous special report for Gospel for Asia (GFA) titled “100 Million Missing Women,” I unpacked the plight of missing women on a global scale and what governments and NGOs are doing to address the problem. The sheer magnitude of a global issue can make it difficult to internalize the gravity of the situation, so in this update, I drill down on a specific aspect of this problem that exists in North America — one that needs to be brought to the attention of the public.

Sometimes, when exploring complex world problems or catastrophes, such as a hurricane obliterating a whole community, it helps me if I sit down for a few moments and withdraw into silence. Then, I take some time to imagine myself and my family dealing with the same kind of total ruin.

So in order to understand the dynamic of what is termed MMIW (Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women), I took some time to ask myself what this might look like in the community where my husband, David, and I now live.

Our town is a little place, thought unexceptional by many. Recently, I was sharing with friends about the winter banners hanging on main street that say: “One Good Friend Warms Many Months.” Our little town is a basically overlooked western suburb with an immigrant community that grew and thrived because, long ago, Campbell Soup planted a large factory here on the far western edge of other suburbs growing around Chicago. That plant now stretches empty and abandoned, covering several acres, a quiet witness to economic collapse.

For the sake of discussion, let me impose a hypothetical situation upon my unremarkable little town with its population of 27,086 according to 2019 Census Bureau data. The real drama from which I would like to draw a hypothetical is the one that has recently been drawing attention from national reporting agencies and that I mentioned in the opening paragraphs. In certain areas of the United States and Canada, there is a horrific epidemic, which some term a “genocide,” of murdered and missing indigenous women. Let me impose the statistical dilemma, now much-reported.

Data on Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women

It was not until 2016 that the government of Canada, under the leadership of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, established a National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. This was a much-belated response to repeated calls from indigenous leaders, social activists and multiple non-government agencies that were outraged that nothing was being done about the growing problem. The term “indigenous people” includes citizenry from First Nations, Inuit, Métis and Native American communities.

In 2011, Statistics Canada reported the following concerning Aboriginal females:

- It was estimated that from 1997 to 2000, the rate of homicide for Aboriginal females was almost seven times higher than other females.

- Compared to non-indigenous females, they were also “disproportionately affected by all forms of violence.”

- They are also significantly over-represented among female Canadian homicide victims.

- They are far more likely than other women to go missing.

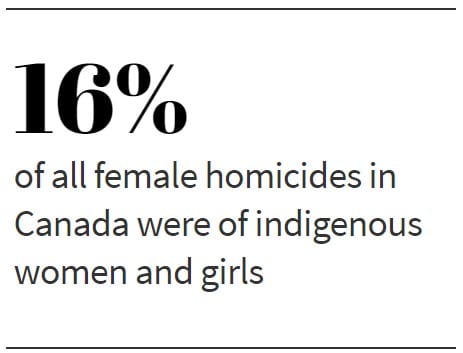

The statistical incidence of MMIW is so high that the Canadian Inquiry reported that indigenous women and girls represented 16 percent of all female homicides in Canada despite representing only 4 percent of the female population.

No wonder activists, journalists, women’s-safety advocates and law-enforcement agencies have now become vocal in their concerns about examining the reasons for such violence committed against mothers, daughters, girls, women, teenagers and children in this population demographic. Not only has there finally been alarm and public outcry about a decades-old dilemma, but several excellent documentaries are also available on the Internet for concerned viewers. What If? and Silent No More and other news specials examine various case studies of missing women.

Using My Little Town as a Hypothetical Example

First, because of the natural tendency not to be concerned by social dilemmas unless they touch our own lives, let’s stop and aside set some time to attempt to build some empathetic concern. Let’s use my little town with its total population of 27,086 citizens as a hypothetical example. Some 51.1 percent of the population of this far-western Chicago suburb is Hispanic. That would be 13,841 people of Latino origin.

For the sake of discussion, let’s divide that number in half, which would broadly represent the population of females within the Latino population of my little town at some 6,920 women and girls. Then, let’s just grab a murdered- or missing-women statistic—let’s say that 24 percent (which pops up in statistics on MMIW dealing with per-hundred ratios, such as the homicide rate for indigenous women in Canada is 24 percent per 100,000 population) of the MMW in my little town would be almost one-quarter of the estimated 6,920 women and girls who live here. Now let’s expand our acronym from MMIW to MMWG (Murdered and Missing Women and Girls).That would be some 1,661 victims who had gone missing or been discovered murdered. Bodies have been found face down in the branch of the DuPage River, discovered in a shallow grave, found lifeless along the Prairie Path where many of us like to walk and jog. Of course, these deaths or unaccountable absences wouldn’t have happened over the period of any one year, but would be the aggregate of some 10, 15 or 20 years—who knows exactly how many decades?

Yet I am certain—absolutely, determinedly certain—that if this kind of quiet-but-steady mayhem had occurred in our community, even in the Hispanic percentage with its immigrant roots and now large immigrant population, a large cry would have developed, a shout of horror that would proclaim that my little town was a dangerous place for women to move into, live in or be born into. Stay away! Be warned! Do not look at real estate or contact a realtor.

In addition, some 67.6 percent of my fellow towners are white. So, an estimated half of that would be 34 percent white women and girls. One-quarter of 34 percent would be how many missing and murdered? You do the math.

I’m even more certain that if the same demographic had been applied to the white citizenry of my little town, the resultant reaction of distress, concern and investigation would have been tremendous. Wealthy folk who could move would do so. Due to the resulting wave of public outcry, more tax dollars would be assigned to the MMWG disaster. Eventually, the hazardous female environment would be examined by sociologists, written about by PhDs, covered in national news and exploited by carrion-feeders who inevitably make their reputations out of the sensational.

An Imaginative Exercise in Empathetic Fear

The physical facts and data regarding Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women are one thing, but imagine, again—if you will, make a leap of attempted understanding—what it must be like for a woman of any age to live in an environment so hostile to her sex that she knows someone who has gone missing or who has been murdered. A grandmother, an aunt, someone’s own mother, a daughter-in-law, a teenager, a teacher, a little girl has disappeared. A body has been found discarded by a roadside. And no one can say for sure exactly what happened. Not only that, the local police don’t take the problem of missing women seriously. Crime labs are overloaded with other, more-immediate concerns. Those gals will show up some day. Someone will find them. They’ll eventually call home.

Think about the nagging uncertainty that comes from running alone for a last-minute errand to a grocery store. Think about driving somewhere alone at night. Think about a walk home from some school event with friends, then think about those last two blocks you must walk alone. Think about a stranger passing you in a car, slowing, getting a good look, then speeding ahead. Think about an argument in a family, about the gun stored and locked in a cabinet but still there. Think about being at home alone. Think about that phone call from a stranger that reports an accident with a family member being harmed and you needing to come to aid.

When there is high incidence of murdered and missing women in any population, doesn’t the normal, the ordinary and the everyday hold the potential of terror? Doesn’t a world surfeited with sunshine, growing things, seasonal changes, rain on the fields and starlight at night get bent out of emotional shape?

And if you or someone you know has survived an attempted incident of rape or kidnapping or brutality, does the world ever seem safe again?

To be caring citizens, we all need to become proficient in these imaginary exercises in order to create empathy for others in distress. In fact, a hallmark of Christian faith has to do with how much we are willing to enter into the suffering of others, into a suffering that at this time in our lives does not touch our present circumstances. In fact, justice mostly begins with a kind of appalled empathy, then it moves to indignation, finally resulting in activism—the attempt to “do something,” to change a wretched environment, to touch one life that has been wrecked by evil.

Read the rest of Gospel for Asia’s Special Report on An Imaginative Exercise in Empathetic Fear — Think about Living in a Community with Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women: Part 2

Learn more about Gospel for Asia’s programs to combat the 100 million missing women reality by helping women through Vocational Training, Sewing Machines and Literacy Training.

This Special Report article originally appeared on GFA.org

Read another Special Report from Gospel for Asia on 100 Million Missing Women.

Learn more about the Women Missionaries who are bringing hope as they share Christ’s love to women in Asia.

Read more on the missing and murdered indigenous women dilemma on gender imbalance and violence against women on Patheos.

Click here, to read more blogs on Patheos from Gospel for Asia.

Learn more about Gospel for Asia: Facebook | YouTube | Instagram | LinkedIn | SourceWatch | Integrity | Lawsuit Update | 5 Distinctives | 6 Remarkable Facts | 10 Milestones | Media Room | Poverty Alleviation | Endorsements | 40th Anniversary | Lawsuit Response |

Notable news about Gospel for Asia: FoxNews, ChristianPost, NYPost, MissionsBox