I only realized the irony of consistently being asked to explain why my name was funny and why we spoke a different language at home to my fellow students at Robina Lyle Elementary School, who, while white and nominally Christian and had names like David and Lisa, nonetheless also owned multi-syllabic Greek and Polish last names full of tongue-twisting consonants and delightfully rhyming vowels, when I reached adulthood. I sincerely answered my classmates’ sincere questions about how many wives my father had, why my mother wore a long dress and covered her hair, and why I wasn’t allowed to attend sleep-overs.

I only realized the irony of consistently being asked to explain why my name was funny and why we spoke a different language at home to my fellow students at Robina Lyle Elementary School, who, while white and nominally Christian and had names like David and Lisa, nonetheless also owned multi-syllabic Greek and Polish last names full of tongue-twisting consonants and delightfully rhyming vowels, when I reached adulthood. I sincerely answered my classmates’ sincere questions about how many wives my father had, why my mother wore a long dress and covered her hair, and why I wasn’t allowed to attend sleep-overs.

I was basically a pint-sized “public Muslim” trying to explain the nuances of my faith and immigrant background, as best I understood them, to classmates and teachers who had little idea how to contextualize me outside of Not Without My Daughter and the first Gulf War.

I didn’t mind it, though, because answering their Islam questions was one of the few ways I interacted positively with most of my classmates. I was usually bullied, ignored or made fun of by most of them – though I did make and retain a few good friends, thankfully. When I wasn’t spending time with my few friends, I found solace and refuge in libraries. I understood Matilda’s loneliness, I marveled at Alice’s bravery and I wanted to grow up to be Nancy. Though I read few stories featuring main (or any) characters of color, I understood, even at that age, that stories can break racial, religious and national barriers. I could easily hear echoes of my own story in the stories of these white, nominally Christian, normative characters. A good story can take an imaginative child to Middle Earth or to outer space and it doesn’t matter how many syllables are in your last name or how dark your skin is. And I believed that I was heeding the Quranic injunction, “Read in the name of your Lord!” After all, “why shouldn’t that include fiction?” asked my 8 year old self. I learned quite a lot from the fiction I read and God encourages us to increase our knowledge!

Inspired by the stories I read, I also threw myself into writing my own short fiction pieces at a young age. I wish I could say that I was inspired by writers like Harper Lee, but the truth was that my stories clearly written by a tween who spent her free time reading the Sweet Valley Twins series. Though I did write a few Poe-inspired faux-Gothic pieces, including a murder mystery set in an ice rink (the skates were the murder weapon!), I typically focused on painting a plot line in which I could see myself as the protagonist. I wrote several pieces set in a New England boarding school, featuring the same impressively international cast, creating the diverse characters I so badly wanted to read about in my own stories.

Usually, I was the only person who read my stories, though I would sometimes submit them for an extra credit grade or share them with one of my friends. Because I assumed that anyone who read my stories already knew about Islam and Muslims, I rarely inserted any teachable moments in the stories and poetry I wrote. I would sometimes have a Muslim main character, or set a scene in a mosque or a Muslim home, but my early forays into writing were more about developing what I thought were broadly aspirational characters and creative plot twists. And I used alliteration as much as possible.

My teachers and parents heartily encouraged my literary drive and I happily spent hundreds of hours imagining the witty wordplay my protagonists would have with their ethnically diverse group of equally droll friends as they solved the mystery of the week. My engagement with the books I read and the characters I wrote filled a void that I felt, having such few friends throughout my public elementary and junior high schools. I later switched to an Islamic high school, where I felt more comfortable, and continued to indulge my literary love affair.

My peers didn’t share my enthusiasm for Dostoyevsky, Shakespeare or Austen, but my teachers certainly supported me. And my written vocabulary was phenomenal. While my parents were fluent in English, they focused on speaking Arabic at home. This meant that while I fully knew the definition of many words that I came across in the books I read, and when to use them, I didn’t always know how to pronounce them (naive, I’m looking at you).

Because I grew up witnessing the genocides in Rwanda and the Balkans, when I started university, I was committed to studying how the global community can cooperate to prevent crimes against humanity and redress human rights grievances. Yet, I yearned to immerse myself in literature. That is why my transcript is full of classes entitled “International Negotiations Theory” and “Ethnic Conflicts in Contemporary Africa” and peppered with others called “20th Century Egyptian Literature” and “The Russian Romantics.” And for the first time in my life, I was surrounded by peers who immersed themselves into reading, who were open to lively discussions about the socio-political issues of the day. I made tons of friends in college and found out that I had always been an extrovert, but that the disinterest of my grade-school peers had forced me into introversion.

I joined the grown-up workforce after the attacks of 9/11 armed with a newly minted International Relations degree, an intimate knowledge of Arab and Muslim American identity, and fluency in Arabic. I worked with immigrant Muslim communities figuring out the citizenship process. I organized immigrant and faith-based communities around issues that affected new Americans. I began giving speeches about Islam and Muslim Americans to church groups. I trained young people to become interfaith leaders on their campuses and beyond. In some ways, you could say that my career path over the last decade spun a grand American narrative.

But I stopped writing.

That is to say, I stopped writing fiction. I stopped dipping into my imagination to create interesting characters, making their way across a diverse world. I did continue to write and share my thoughts publicly, outrageously aided and abetted by social media, but I unwittingly narrowed my topics to focus on issues of race, religion and identity in a diverse world. A point about social media: I may or may not have a medical addiction, but I certainly spend a lot of time on various social media platforms. They allow me to share my views publicly and receive instant feedback from the world (including from my British Empire-loving troll. Cheerio, old chap!). In the 21st century, if you’re someone with an idea or advocating an issue, then you’d better be online. Social media is a must in my line of work, but it also gives someone like me instant gratification: I get to engage with people around the world, read their stories and share my own, all in real in time. Though to be completely transparent, not all my social media platforms are focused on issues of identity and global politics; in fact, the online community to which I belonged the longest is an international figure skating group.

I love social media. But sometimes I suspect that it has kidnapped both my imagination and attention span. I’ve had writer’s block for almost a decade and find myself struggling to focus while reading non-fiction books. I’d rather respond to my 1001 notifications than read a new translation of an early version of the 1001 Arabian Nights. These may not completely stem from social media, but the way I engage with the world online has certainly exacerbated these tendencies. Most saliently, I worry that the way I use social media has led made me an adult, professional version of the pint-sized public Muslim who would hold impromptu Islam 101 Q&A sessions at the Lyle playground.

The problem with being a Professional public Muslim is that it’s boring and reductive. A Professional Public Muslim is a terrible protagonist. The Professional Public Muslim is a faux-journalist, always reporting, sometimes analyzing, the stories found in her society. Certainly there’s a place for people with intimate knowledge of being Muslim American to be heard in the public space. But with no spiritual or artistic outlet, it can be exhausting. And there often very little room for the Professional Public Muslim to be the Creative Muslim, to be the agent of her own story, her piece of the grand narrative.

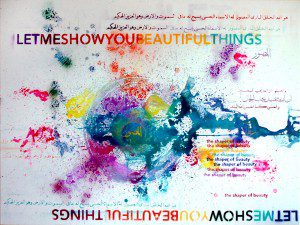

I look back at the discussions Public Muslims have had online in 2014 and I see a pattern. The deeply divisive social media back and forth over Abu Easa-gate, the Shalom Hartman Institute’s MLI program, and the call to boycott the White House iftar seemed to only cleave the activist Public Muslim community further apart. But the creation of a Muslim superhero and the wide appeal of Muslim-origin satirists, secular though they may be, tell a different story. Art and stories and music – created culture – shine a light onto narratives we might otherwise not hear nor tell. Throughout Islamic history, wherever Muslims went, they created culture: they built on a rich poetic tradition, commissioned cutting edge architecture, and enriched empires through art, calligraphy and design. Not as a matter of winning hearts and minds, but as a way to engage with local cultures, resulting in beautiful and unique hybrid creations.

In a recent NYT interview, filmmaker Musa Syeed articulates the need and desire for creative outlets.

“When I was growing up, we were sort of raised to have talking points: This is how you respond to this question about Islam. It was always such a heavy thing to carry, and when I carried that into wanting to make art, it was always very heavy handed, very much about how to convince people of my validity. The more I feel like I have to prove something about Islam, the worse the art is and the worse a Muslim I become.”

My literary upbringing was quite a cultural hybrid, but uniquely American. I read European fairy tales before bed on the nights my parents didn’t share the East African folk stories they grew up with. I immersed myself with equal vigor reading Tolstoy as I did the Baby-Sitters Club books. The words of Langston Hughes and WEB Du Bois are the lenses through which I learned to view American history. I believe that The Crucible is as relevant today as it was during the McCarthy era.

I’m not content anymore to merely report, react to, and analyze the public discourse around what it means to be a citizen in a diverse secular democracy. I want to create. I want to write. It will be difficult to pick up the pen again (so to speak). I am not as confident today in my creative writing abilities as I was at 15 (I was very confident; I thought I had Matilda’s smarts, Alice’s guts and Nancy’s savvy). I may not be talented enough to be published. But it’s not about getting published – after all, I have my many social media platforms through which to amplify my own voice. It’s about letting my imagination loose, shutting off my 1001 notifications and creating stories in the only authentic voice I have – my own.