How might social psychology contribute to our theological and missiological thinking? Nisbett’s book The Geography of Thought: How Asians and Westerners Think Differently…and Why (Free Press, 2003) is one of the more exciting books I’ve read in terms of both explaining differences between East-West thinking and also backing it up with empirical research.

I won’t do a full review here. One qualifier for those who decide to read it––he starts off with some (pretty reasonable) historical conjecture, then defends the conclusions with research data. Frequently, books work the other direction (proof to conclusions), so I don’t want readers to be turned off by the first 20-30 pages where they might assume Nisbett is making a sheer assertion.

I want to give an example of how missiologists and theologians can use the insights of social psychology. I would after all agree with David Clark that our method of theologizing-contextualizing needs to be dialogical.

In one experiment, Nisbett and a colleague explore the tendency of Westerners to dichotomize (use either/or thinking) in contrast to Easterners’ preference for harmonizing ideas (using both/and thinking). First, I’ll insert an excerpt from the book, then comment afterward.

“What would happen if Easterners and Westerners were confronted with apparently conflicting propositions? The logical approach would seem to require rejecting one of the propositions in favor of the other in order to avoid a possible contradiction. The dialectical approach would favor finding some truth in both, in a search for the Middle Way.

In order to examine this question, Peng and I asked undergraduates at the University of Michigan and Beijing University to read what we described as summaries of the results of several social science studies. There were five different topics altogether and we asked participants either to read about a study reporting a particular finding, a study strongly implying something quite different, or both. The opposing studies did not necessarily contradict each other in a logical sense, but at least had the character that, if one was true, then the other would seem to be quite unlikely to be true. The pair of statements below was typical of the more obviously contradictory ones” (Kindle Locations 2351-2358).

After explaining the experiment further, Nisbett continues:

“What inferences should the participants have made? That seems pretty clear. The participants who were exposed to two propositions that are apparently contradictory ought to have believed in each of them less than those who knew about only one. This should be particularly true for less plausible propositions that are countered by more plausible ones.

But neither the Americans nor the Chinese behaved that way. The Chinese who saw both propositions reported about equal belief in both. They properly rated the more plausible proposition as less believable if they saw it contradicted than if they didn’t. But the Chinese rated the less plausible proposition as more believable if they saw it contradicted than if they didn’t. This inappropriate inference would be the consequence of feeling it necessary to find the truth in each of two contradictory propositions.

The Americans, instead of converging in their belief in the two propositions, actually diverged, believing the more plausible proposition more if they saw it contradicted than if they didn’t. This seems the likely result of feeling it necessary to decide which of two conflicting propositions is correct. But it’s pretty dubious inferential practice to believe something more if it’s contradicted than if it isn’t. My guess is that the Americans behaved the way they did because they are good at generating counterarguments— a skill that comes from a lifetime of doing just that. When confronted with a weak argument against a proposition they are inclined to believe, they have no trouble in shooting it down.

The problem is that the ease with which they generate counterarguments may serve to bolster their belief in a proposition that ought to seem shakier if it is contradicted than if it is not. There is evidence in fact that Americans do tend to generate more counterarguments than Chinese do. In effect, Americans may not know their own strength, failing to understand how easy it is for them to attack an argument they find implausible” (Kindle Locations 2372-2386).

I won’t write an entire essay here.

Still, think with me of the implications for theology. Many of our theological conclusions and convictions may stem from our basic cultural wiring as much as other factors. This does not lead to relativism or a fatalistic view of interpretation.

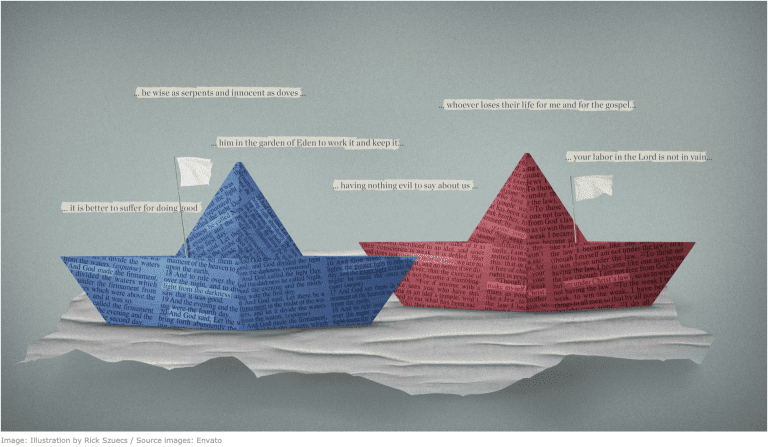

However, the strength with which we hold a position and thus our openness to other ideas may result from our habit of mind to either harmonize or dichotomize. I wonder how many controversies in church history reflect an inability to think in terms of both-and (rather than simply either-or). To compound the problem, Christians think they are “defending truth” against error and heresy when, in fact, the dispute is simply one of emphasis.

Naturally, there are implications for missions. In contextualization attempts, mission strategy, and social adjustment, the propensity to polarize options will doubtless result in conflict and frustration. Consequently, this habit of mind could cut short a missionary’s career and stunt effectiveness in ministry.

What are some other applications of Nisbett’s experiment/observation? What about social psychology in general? Any reading suggestions or implications for missiology and theology?