What do recent debates about justification have to do with China? In the last post, I summarized the traditional view (sometimes called the “Old Perspective on Paul“). In the past 30+ years, more and more scholars have adjusted their views due to the influence of what is called the “New Perspective on Paul” (NPP).

What is the New Perspective on Paul?

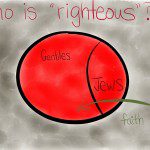

The NPP emphasizes one particular point above others: Paul’s doctrine of justification confronts the problem of ethnocentrism, not simply that of ethical moralism. (Different strands of the NPP tease out the implications of this idea in diverse ways.) The Jews of Paul’s day were not mere legalists trying to earn their way to heaven. Because God has chosen Israel as his special people, salvation comes through the Jews. However, Paul opposes the idea that people must first become Jews in order to be reckoned righteous. The NPP focuses more on the question: Who are God’s people?

The NPP emphasizes one particular point above others: Paul’s doctrine of justification confronts the problem of ethnocentrism, not simply that of ethical moralism. (Different strands of the NPP tease out the implications of this idea in diverse ways.) The Jews of Paul’s day were not mere legalists trying to earn their way to heaven. Because God has chosen Israel as his special people, salvation comes through the Jews. However, Paul opposes the idea that people must first become Jews in order to be reckoned righteous. The NPP focuses more on the question: Who are God’s people?

In Romans and Galatians, being “righteous,” while having moral connotations, primarily refers to a status given to people by God. A righteous person was someone in good standing within God’s covenant. In biblical terms, being “righteous” is not equivalent to being “perfect.” After all, the Law itself established a sacrificial system that presupposed that people would sin.

Instead, being righteous concerned one’s identity and sense of loyalty (i.e. to the Lord). Obedience to the Mosaic Covenant signified that one was a Jew. When Gentiles received circumcision, they identified with the God of Israel and in this sense represented their “conversion” and inclusion into God’s people, i.e. Israel according to the flesh.

In the graph above, there are two kinds of people. There are Jews (represented by the circle) and Gentiles (outside the circle). The Mosaic Law acts as a boundary marker. Obedience to the Law (e.g. circumcision, Sabbath keeping) signifies allegiance to the God of Abraham and the nation of Israel. The Law is not simply God’s “moral law” (for humanity), understood abstractly.

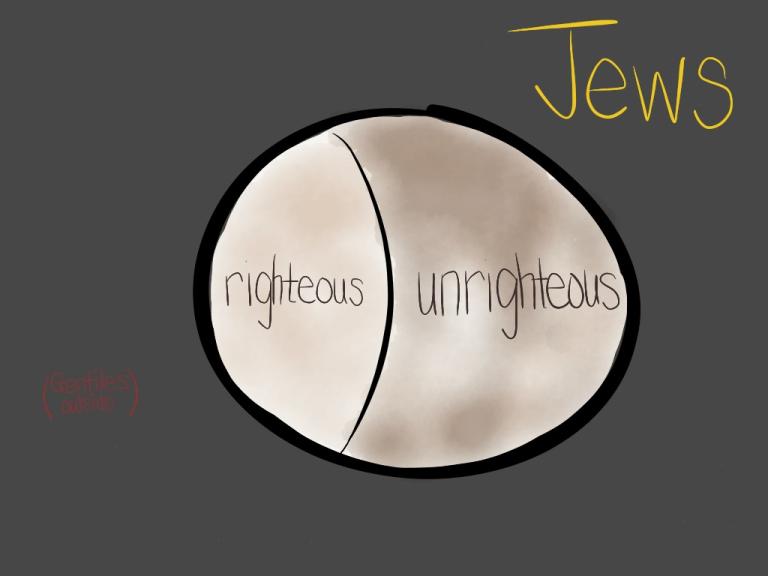

Of course, Paul’s Jewish opponents were not asserting that one was saved simply because of bloodline. While law keeping was necessarily to “get in” to God’s covenant, so also it is needed in order to “stay in.” The Jews certainly recognizes the reality of unrighteous, reprobate Jews within Israel. In that respect, the graph above distinguishes God’s people (i.e. Israel) into two types––those who faithful to keep the Law and those who are “Jewish”, for example, by birth but neglect to obey God’s commands.

A Summary of the Two Perspectives

In a nutshell, what can we say?

According to the OPP, Paul divided the world into the “righteous” and the “unrighteous,” irrespective of ethnic identity. Paul opposed works-righteousness and affirms faith as the way in which one is saved. Stress is given to how one is saved.

In contrast, the NPP says that Paul confronts Jewish ethnocentrism. According to Paul’s opponents, keeping the Mosaic Law meant being/becoming Jewish. Paul thus affirms faith as a way of saying that God’s covenant with Abraham is not limited to Jews according to the flesh. Instead, Gentiles also can be reckoned righteous. Greater emphasis falls on the question who can be saved.

The implications are too many to flesh out here. This topic concerns everything from how we interpret various passages, to salvation, our doctrine of the church, etc.

Traditionally, Chinese like to find a middle way between extremes. How might we reconcile these two positions? I’ll explain in a coming post.

Photo Credit (Yin Yang): CC 2.0/wikimedia