Chinese culture may help us reconcile the “New Perspective on Paul” (NPP) and the traditional view of justification.

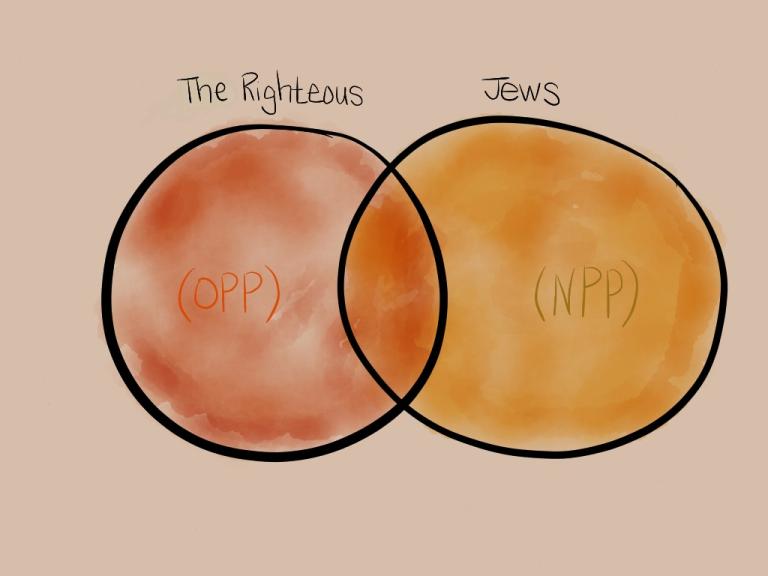

Accordingly, we can also expect the NPP debate to have key implications for ministry in China and elsewhere. In a previous post, I offered two graphs that summarize the NPP and the traditional “Old Perspective on Paul (OPP). Now, I want to bring the two together in the graph below.

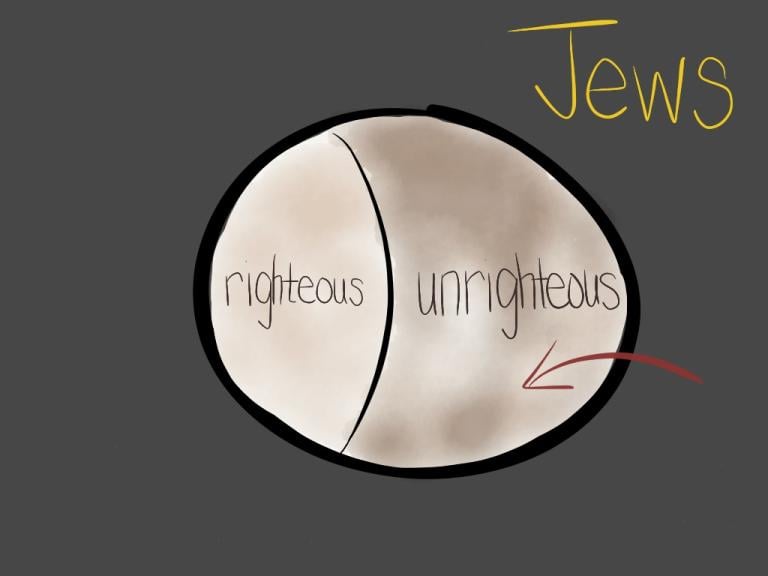

The left side represents the way the OPP understands the Jewish problem with justification as described in Romans and Galatians. Paul and his Jewish opponent divide the world into two types of people–righteous and unrighteous. One is justified through faith in Christ, not good works.

The right side reflects the thinking of the NPP. Humans are divided into two groups–the Jew and the Gentile. The NPP says that justification primarily solves a problem with ethnicity not ethics.

Is there any hope to reconcile these two views? It seems the two camps have fundamentally different starting points. However, I think that if we will first put on a Chinese cultural lens, we will see how the two perspectives come together nicely.

Putting on a Chinese Lens

It all starts with face. As I argued in Saving God’s Face and on the blog, there are two ways on gets face (honor and shame). One achieves face via accomplishments and good deeds. Western theology has long emphasized this aspect. In addition, people are “ascribed” face according to one’s position, relationships, gender, one’s hometown, etc.

Everyone wants face. It’s the way we were made. It’s not sin. This is because face is about our sense of value and our place of belonging. Christians before God don’t want to “lose face” but rather “have face.” We want to be reckoned as one of his people.

This same sort of dynamic is at play in Paul’s discussion on justification. Ancient Jews, like people of every time and place, wanted honor not shame. A Jew wanted to be regarded as a “righteous person.” This of course was a term of honor. At one level, to be righteous signified identity, that one belongs to God’s people. At another level, it could point to one’s actions.

In the eyes of the Paul’s Jewish contemporaries, the greatest honor consists in belonging to God’s people. Presumably, this implied being righteous. (“Righteous” is not synonymous with the word “perfect.”) Thus, within Israel, simply being a Jew would afford/ascribe a person more honor than the “unrighteous” Gentile. However, one’s piety could bring a person further honor. For example, a Pharisee would win greater social praise than a less disciplined person.

We can begin to see the problem Paul is facing. Achieved and ascribed honor correspond with the fact that, for the Jews, being “righteous” had moral and collective connotations.

What does it mean to be “righteous”?

Is “righteousness” a moral/ethnic or covenantal category? That is precisely the wrong question that shapes so much of NPP debate.

Keep in mind that God in history had chosen a particular nation, Israel, to represent him in the world. God would use Israel to bless the entire world. Yet, what happens when Jews began to misunderstand their election? By Paul’s day, many Jews saw themselves primarily as the primary recipients of God’s blessing, as opposed to being the channel through which the Gentiles would be blessed. This error radically distorts God’s covenant with Abraham and thus their Israel’s view of the Mosaic Law.

Consequently, the Jews mistakenly collapsed their categories of thinking. Having sharply separated Israel from Gentiles, they misunderstand justification. They presumed that if God declares someone “righteous”, that person would be a Jew, i.e. one who identifies with the one true God and his people Israel. (This is not the same thing as saying all Jews are righteous.)

According to this way of thinking, being justified presumed being Jewish and thus keeping the Law. By means of circumcision, etc., one signified himself as belonging to Israel.

Therefore, the “ethnic badge” became an “ethical” distinction. Belonging to God’s covenant (whether Abraham or Moses) was restricted to Jews. In this respect, being justified/righteous (in their view) implied ethnic identity. We can see the distortion in their thinking more clearly.

Practically, Law-keeping had functioned as an ethnic boundary marker; yet, it also came to be seen as a condition (basis?) for ultimate justification (vindication) and salvation.

In short,

1. Being justified by God implies being Jewish.

2. Being Jewish implied one kept the Mosaic Law.

thus,

3. Keeping the Law both signified ethic identity and was a necessary condition for justification.

Ascribed and Achieved Righteousness

How do we put the discussion about honor and shame together with the debate concerning justification?

Paul’s opponents wanted the honor of being considered “righteous.” From different perspectives, this honor could be ascribed or achieved. While some Jews may have sought achieved honor/righteousness, others would be well content with the ascribed honor via group membership.