In talking about justification, Paul first answers the who-question, then the how-question. That was the point of my last post. Why does it matter?

Why order matters

Sadly, Western theology rarely stresses the identity question; instead, the greater emphasis is given to the how question (how is one justified?). Why do the Jedi masters of theology confuse the “who?” and “how?” questions?

If we only talk about “achieved righteousness” (i.e. works vs. faith), we can quickly lose the historical context in which people would think of themselves as righteous by virtue of group identity (Jew rather than Gentile). The latter is “ascribed righteousness.” Accordingly, justification quickly becomes abstracted from history. If we first talk about how to get saved, we can easily forget that Paul is facing a who-question.

However, if we recognize that Paul is confronting the problem of Jewish ethnocentrism, then we can still easily see how some Jews would seek after “achieved righteousness” (i.e. legalism). After all, striving to obey the Mosaic Law would only have been an honor within a Jewish worldview. Within a Jewish community, no doubt some people would try to achieve greater levels of honor and “righteousness.” In short, the who-question naturally leads to the how question (as we will see below).

When we first recognize the ethnicity problem, we still have the ethical dimension. Yet, if we start with ethics (per traditional western theology), then we quickly overlook the ethnicity problem. I sometimes put is this way: The traditional interpretation is a right application of Paul’s message: “People cannot do good works to earn their salvation.” However, Paul’s meaning is “Gentiles can also be Abraham’s offspring.”

In this way, I completely affirm the traditional view yet I also retain Paul’s original message so immediately relevant to Eastern cultures. We can give up the false dichotomy between the “old” and “new” perspectives.

Who belongs to God’s Covenant?

The New Perspective on Paul (NPP) often talks about people being “in God’s covenant.” In response, their critics often ask, “What covenant are you talking about?” I’ll give my answer–––the Abrahamic covenant. For example, see Romans 4.

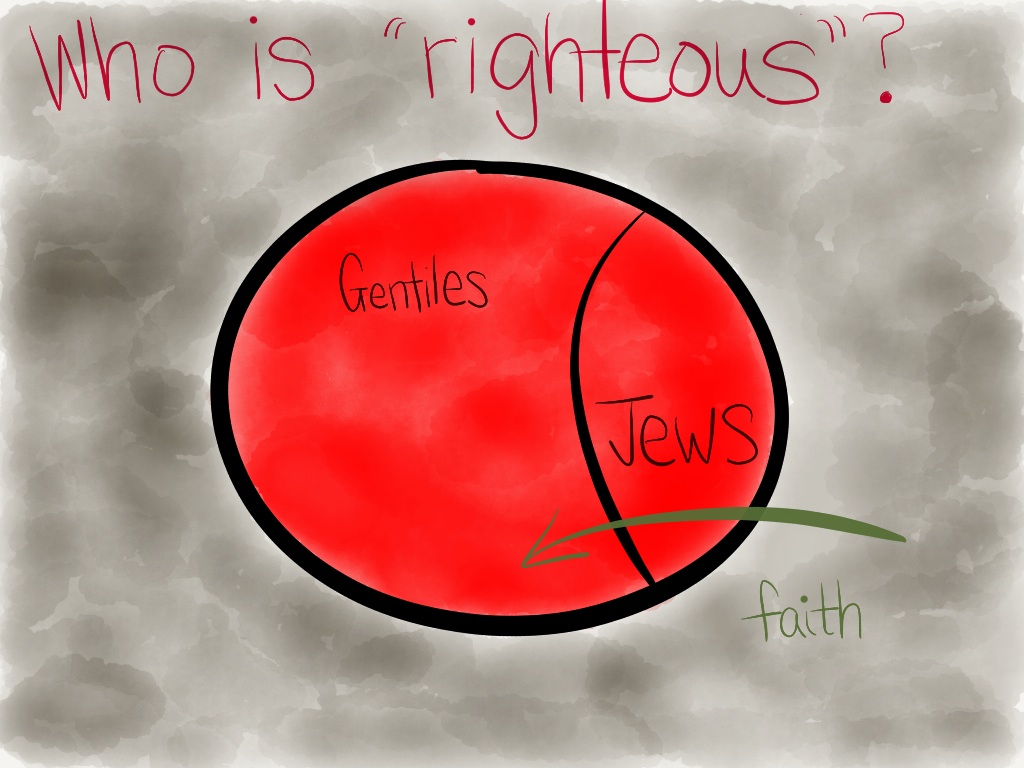

In previous post, I noted that the Jews in Paul’s day had collapsed two categories together–– salvation and society. In preaching justification, Paul confronts more than just a “social” problem (ethnicity). He is also doing more than rebutting legalism (ethics). The Jews thought Gentiles had to become Jewish in order to be justified. In the mind of Paul’s Jewish opponents, “being righteous” carried both ethnic and ethical connotations.

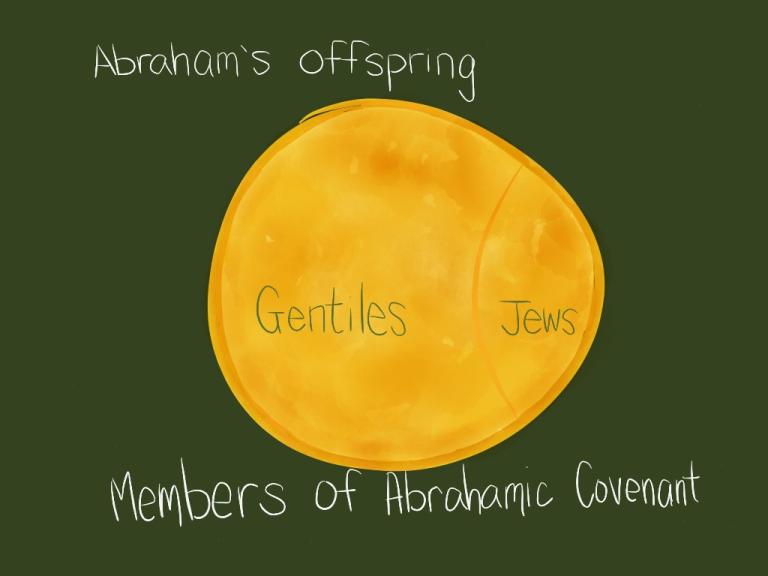

Accordingly, our view of justification goes wrong if we simply divide the world into the “righteous” and “unrighteous” without reference to the concept of “covenant.” Apart from this covenant theme, we abstract Paul’s meaning when he speaks of “righteousness.” As Romans 4 makes plain, being justified (declared righteous) meant being included in Abraham’s covenant (cf. Gal 3:13-14).

Therefore, we need to change the terms that are traditionally used when talking about justification. The graph above adapts the original graph (below) that I used when describing “Old Perspective on Paul” (OPP). Instead of using the blanket term “righteous,” we should reclaim Paul’s language, as when he talks about who can be Abraham’s “offspring.”

We must not settle for a merely “correct” word at the expense of losing the biblical and theological context of justification. If we settle for the ethical dimension of “righteousness,” we easily lose Paul’s ethnic focus.

This matters for ministry. We compromise the gospel message in China when we settle for a true but abstract truth.

“How to make a baby”

Here is an analogy to illustrate the importance of this entire who versus how distinction.

If I claimed, “Men can have babies,” you would naturally rebut my who-question by talking about HOW people have babies. Perhaps, a debate would then break out where everyone begins focusing on the nuances of the subject: “Exactly how do we make babies?” Eventually, that fixation on method distracts us from the original question.

By the time we have decided that implantation and other more traditional means can both produce a baby, we have forgotten that we first wanted to answer a who question.

Talking about how was essential but, in the end, we still missed the point.