In the previous post, I asked a question people have been asking, “What does the fox say?” But then we looked at a more important question, “What does the gospel say?”

Sadly, people often have the same reactions to both: If it’s not “I don’t know,” then they might just guess. This was a first response I listed in the last post. There is a second frequent response to the question, “What does the gospel say?”

Sadly, people often have the same reactions to both: If it’s not “I don’t know,” then they might just guess. This was a first response I listed in the last post. There is a second frequent response to the question, “What does the gospel say?”

2. A lot of people simply assume they understand the gospel.

People get a bit startled when I tell them that we should not “assume” the gospel. Isn’t the gospel foundational? If we can assume anything, isn’t it the gospel?

Let me say from the start––there is only one gospel. However, there are many ways to express it. I’m not just talking about modern evangelism; even in the Bible, we find diversity in gospel presentations.

The problem comes when we confuse a certain perspective on the gospel with the gospel itself. Every gospel presentation uses some sort of theological framework. We always express the gospel using a particular formulation consisting of one or more metaphors, points of emphasis, and/or set of texts.

It is very possible to assume correct doctrine and yet distort the gospel message in a way that makes it hard for people to understand our message. This is exactly why I frequently talk about compromising the gospel by settling for truth.

What Happens When We Assume?

In chapter 2 of my book, Saving God’s Face, I show in detail how many evangelical assume the gospel. This has detrimental effects on evangelism and contextualization in particular. Here is how I introduce the subject:

If we assume the gospel in contextualization, we commit a logical fallacy by begging the question. Accordingly, assuming the gospel largely predetermines the results of contextualization. Thus, begging the question renders faithful contextualization all but impossible. The problem is systemic since all Christian theology centers on the question, “What is the gospel?” This goes beyond saying that theological background inevitably influences contextualization. Missiologically, if the gospel is presupposed, what is the value in doing theological contextualization? By examining this tendency to make premature assumptions, contextualization methods can be corrected and improved.

One who writes about theology and contextualization can tacitly assume a particular formulation of the gospel and even open a door to syncretism. While many affirm the centrality of Jesus’ life, death, and resurrection, there is too little explicit focus on what exactly should be contextualized. Consequently, syncretism goes unnoticed since the contextualized theology does little more than restate a doctrine in traditional theological categories. Many scholars may not see the problem since their definition of “syncretism” is limited to only that which deviates from the gospel. Yet, theological syncretism also results when culturally bound conceptions of the gospel become the assumed framework of contextualization. It is easier to identify syncretism with a foreign culture than the sort of syncretism that grows from a traditional theological system.

… presupposing a gospel a priori thwarts and potentially sabotages theology from the start. It concludes by arguing that contextualization is an act of biblical interpretation, not simply the application or communication of biblical truth.

When we assume the gospel, we risk either cultural syncretism or theological syncretism. Even if we don’t completely compromise the gospel, our message will seem incoherent or irrelevant.

Contextualizing for a fox?

Contextualizing for a fox?

Foreigners typically struggle with the tones when speaking Mandarin. One trick some people use is simply talking faster. If you talk fast enough, the tones all blend together and sometimes a person can fake it. That’s not a good long-term language learning strategy.

In the “What does the fox say?” video, the singers don’t know what a fox says, so they just try different forms of babbling, cackling, barking, or whatever other sound they could think of. But guess what? In the end, no one would say that they are speaking the fox’s language.

If they were trying to contextualize the one gospel for a fox, they are not using a good long-term contextualization strategy. Contextualization is not simply saying anything that sounds reasonable. Even if they were to accidentally speak “fox language,” they would not be able to communicate anything meaningful (in whatever sense we might say a fox makes an intentional noise). Something can be true and yet lack significance for the people who hear it.

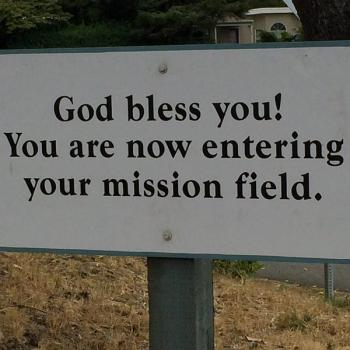

This is the goal of contextualization––to understand, convey, and apply the gospel in a way that is not only true but expresses its significance.

Even if we knew what a fox said, would we know what it meant?

How do we contextualize the one gospel in any culture? We begin by asking “What does the gospel say?” We should not simply assume we already know.

Photo Credit: CC 2.0/wikipedia

Related articles

- One of the most important quotes I’ve read on contextualization (www.patheos.com/blogs/jacksonwu)

- The Gospel with Chinese Characteristics (www.patheos.com/blogs/jacksonwu)