In chapter 7 of Christian Political Witness, William Cavanaugh suggests that our political witness is compromised when we see the church merely as a collection of individuals rather than a corporate person. In so doing, the church both creates and perpetuates class divisions that the gospel seeks to eliminate.

(I’ll explain more in the second half of this post.)

Cavanaugh provides a profound analysis of a complex topic. I don’t pretend that a few paragraphs will not do justice to his chapter. I will simply highlight the broad contours of his essay.

Premise 1: The gospel creates a community, called the “Church,” that transcends social/class boundaries like ethnicity, economics, and gender. One thinks of Gal 3:27–29.

Premise 2: Democracies with market economies create a class system contrary to the gospel.

He uses a case study to make his overall point. Cavanaugh discusses a recent Supreme Court case in which the court ruled that corporations and unions should be treated like individuals when it comes to making campaign contributions in the American democracy. What are the implications when corporations are treated as individuals?

He begins by making two basic points:

1. Democracies are based on the premise that political power is distributed equally to individuals. Equality is the key value.

2. Capitalism distributes goods on the principle of supply and demand. In capitalistic economies, individuals are free to sell their labor. Capitalism gives power to individuals according their economic productivity. Economic power is determined by wealth. Here, freedom is the key value.

According to Cavanaugh, the American Supreme Court decision practically means that freedom (in economics) trumps equality (in politics). Why? Corporations and unions wield greater political power by virtue of their greater wealth. Consequently, the political influence of actual human individuals is relativized; as a result, the only power afforded them is economic.

As wealthy capitalists (managers, CEOs, etc.) exert unequal political and economic power over lower classes of workers, the gap widens between the upper and lower classes. The preferences of the wealthy effectively strip the poor of power in the quest to maximize economic profit. Accordingly, legislation is passed and wages are kept low, which ensure that people remain within their economic caste.

Conclusion: When capitalistic freedom trumps political equality, social injustices emerge which contradict the gospel’s vision of a kingdom without classes.

What’s the application?

A Church Divided Will Not Stand

In both East and Western cultures, power or influence is distributed according to who has face, i.e. “social currency.” People get “face” based on a number of factors, including education, wealth, location, titles, and group membership. “Social currency” is not always distributed evenly. When this happens, a class system emerges. Therefore, I will identify a few dynamics that similarly divide the church into various social castes.

1. Is the church one or many?

Cavanaugh’s argument highlights a simple point: metaphors matter. There are practical implications to the way we conceive of the church. Thus, the church is a body, not a market. However, if we regard the church as a mere collection of individuals, a social caste system inevitable emerges within the church.

The reason is subtle but important. The church effectively begins to function like market economy of social exchanges. Decisions within the church tend to be “subsumed into a competitive market model based on preferences rather than any substantial telos or conception of the common good.” When this happens, “there is no standard on which to judge which social purposes are to be pursued” (143). In short, the preferences of a few select members reign supreme whenever the church does not see itself as a body.

Is it any wonder then that the church misses significance of marriage as signified within Ephesians 5? When the relationship between “Christ and the church” becomes hyper-individualized, it is also far more difficult to grasp what it means to be “one flesh.”

2. Where is the church?

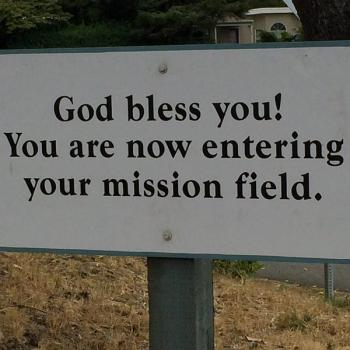

One of the most political decisions we ever make is choosing where we live.

When a family decides to move to the suburbs or a planned community, they have already determined the nature and extent of their social/political participation. We simply will not engage the same issue on a regular basis when we live so far removed from the vast number of social problems that confront urban centers.

Dense populations of wealthier and more educated Christians often consolidate in planned communities outside cities. With their money and education comes the ability to engage in certain ministry initiatives. Naturally, their absence in the cities thus means that urban churches will have less ability to pursue the well-being of their city. By concentrating resources in a few churches, the churches, the Body of Christ is handicapped. This renders Christ’s followers less able to minister strategically, holistically, and effectively.

In addition, the sheer distribution of wealthier Christian taxpayers will influence the development of urban neighborhoods. By moving into cities, tax revenue will be reallocated to areas where improvements in infrastructure and education are most needed.

In the past decade, I have been amazed at how many people I know have conveniently been “called” to plant new churches in already densely churched suburban neighborhoods where schools are nicer and it is easier to secure funding.

These are just a few ways that our decision about where to live de facto perpetuates social classes within the church.

With respect to the global church, we could use a similar line of reasoning. The wealth of the West translates into disproportionate influence in the global church. Western theologies and practices will be the implicit expectations if non-Western churches expect to receive assistance and training from Western churches and mission agencies.

3. Who belongs in the church?

Taking church membership seriously is foundational to a Christian political witness.

Deciding who are “insiders” and “outsiders” inherently communicates the values and expectation that shape a church community. This is where we begin to express what we mean when we say that the church is an expression of an alternative kingdom to world order.

An uncomfortable corollary follows. Church discipline is critical for a Christian political witness. A significant passage is 1 Cor 5:11–13. Paul writes to the Corinthians,

“11 But now I am writing to you not to associate with anyone who bears the name of brother if he is guilty of sexual immorality or greed, or is an idolater, reviler, drunkard, or swindler—not even to eat with such a one. 12 For what have I to do with judging outsiders? Is it not those inside the church whom you are to judge? 13 God judges those outside. “Purge the evil person from among you.”

In 1 Cor 6:2–4, Paul shames the church by reminding them,

“Or do you not know that the saints will judge the world? And if the world is to be judged by you, are you incompetent to try trivial cases? Do you not know that we are to judge angels? How much more, then, matters pertaining to this life! So if you have such cases, why do you lay them before those who have no standing in the church?”

Few passages are as relevant to a Christian political witness than 1 Cor 5–6.

To state everything I’ve said more directly,…