It is very possible that we do not honor biblical authority precisely by forcing an overly literalistic interpretation on the text.

Why? A “literal” reading (from our perspective) may in fact overlook the biblical audience’s cultural context. Accordingly, we might impose our assumptions onto the text, resulting in interpretations that ignore the writer and audience to whom God originally revealed Himself.In The Lost World of Adam and Eve, Walton clarifies what it means to affirm the Bible’s authority. (He elaborates on this topic more fully in The Lost World of Scripture.) He says:

“The authority and inerrancy of the text is, and has traditionally been, attached to what it affirms. Those affirmations are not of a scientific nature. The text does not affirm that we think with our entrails (though [the Old Testament] communicates in those terms because that is what the ancient audience believed.) The text does not affirm that there are waters above. The question that we must therefore address is whether the text, in its authority, makes any affirmations about material human origins. If the communication of the text adopts the “science” and the ideas that everyone in the ancient world believed (as it did with physiology and the waters above), then we would not consider that authoritative revelation or an affirmation of the text” (TLWAE, 20–21).

As ministers of the gospel, biblical authority is foundational. If we desire to contextualize the gospel in a way that is biblically faithful and culturally meaningful, we must honor the Bible’s authority.

This is the genesis of biblical contextualization.

If we truly want to acknowledge the Bible’s authority, then we must be mindful of the original cultural context from which the texts comes from.

I suggest that Walton’s comments about biblical interpretation are helpful for cross-cultural workers, who seek to contextualize the gospel.

A Cross-Cultural Perspective

It is critical for contextualization that we have a cross-cultural perspective.

Keep in mind that we also “cross cultures” when we study history. Cultures in history are just as different as are two modern cultures on opposite sides of the world. When people think about contextualization and “crossing cultures,” they typically think “horizontally,” i.e. about global cultures, as when a Russian travels to South Africa or a German moves to Thailand.If missionaries want to do biblically faithful contextualization, they will need to cross both “horizontal” and “historical” cultures.

In other words, we need to know world cultures AND we need to know ancient biblical cultures.

I try demonstrating an example of this sort of contextualization in Saving God’s Face.

Culture is a “Filter”

Already, in Saving God’s Face, I argued that contextualization begins with interpretation, long before we get to the work of communication and application. Whether one agrees with Walton’s view of Genesis or not, his work highlights the importance of exegesis, biblical theology and worldview.

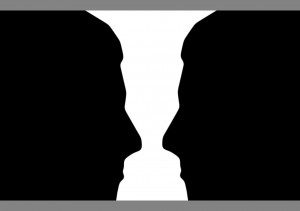

We all come to a text from a vantage point. Our particular cultural lens acts as a “filter.” Culture is not “authoritative” in the way the Bible has authority. Nevertheless, culture inevitably helps or hinders us. It either enables us or prevents us from seeing what in fact is in a text.

I’ve heard people dismiss this claim by saying that we can simply go back and red ancient literature in order to have an ancient worldview. Well, yes, I agree in part (as I’ve said above). However, we can never totally read the ancient documents with ancient eyes. Our own culture filters when we see when we read Josephus, Philo or any number of ancient writings.

This is a major aspect of my model of contextualization, which I propose in my forthcoming book called One Gospel for All Nations: A Practical Approach of Biblical Contextualization.

Photo Credit (illusion): CC 2.0/en.wikipedia

Photo Credit (globe): CC 2.0/commons.wikimedia.org