How did honor shape evangelicalism in the American south before the civil war? Robert Elder answers this question in his new book The Sacred Mirror: Evangelicalism, Honor, and Identity in the Deep South, 1790-1860.

Readers can gain a better grasp how honor-shame work in various cultures. More importantly, I think his book will equip the church to learn lessons about how ot to repeat old mistakes. Below, I link to a few interviews with Elder.

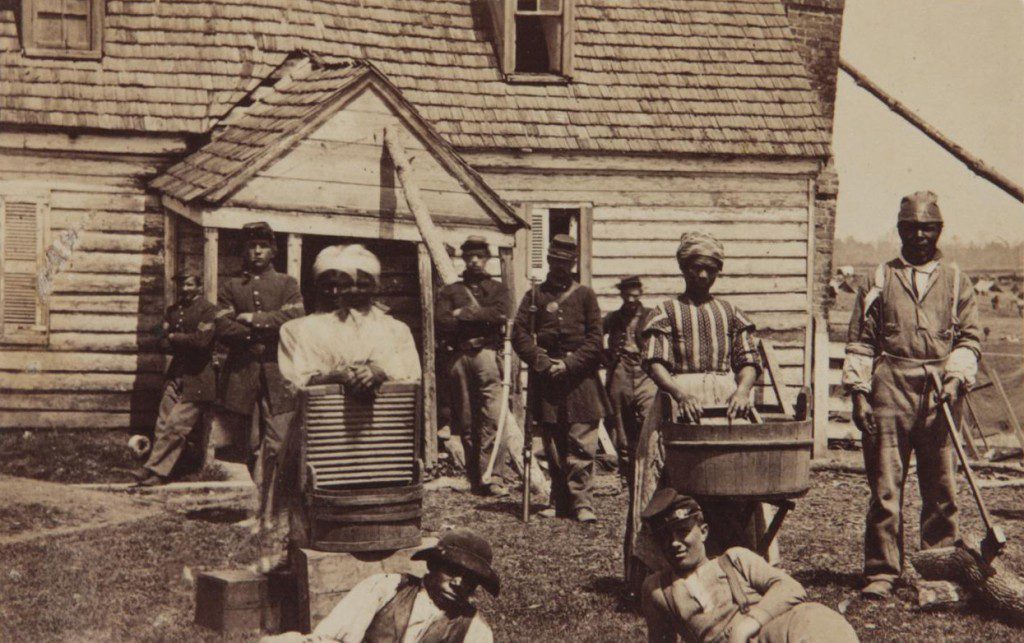

Redefining Honor & the Shame of Slavery

1. Thomas Kidd has a fantastic interview with Robert Elder. Here are a few quotes from the interview that jumped out at me.

Early evangelicals may have critiqued what they called “worldly honor,” but they didn’t discard or reject the idea of honor, or of shame. They simply redefined the community of reference. They drew on biblical texts to argue that “true honor comes from God alone” (John 5:44) and that true (and everlasting) shame belonged only to those who rejected their message.

What a relevant insight for our day!

Regarding slaves’ desire to be members of a church:

But if we understand slavery as a constant dishonor—some scholars use the term “social death”—then enslaved people would have experienced the rituals of evangelicalism, such as baptism, the Lord’s Supper, and church discipline, as rare acknowledgments of their claims to personhood (which is basically what honor is).

Church Discipline & Authority

2. Elsewhere, historian John Fea also interviews Elder, who connect honor with church discipline:

I found that church discipline, which was a very public process, was a powerful site for determining honor and shame in a culture that gave great weight to communal authority and opinion.

He adds,

I argue that evangelicalism in the pre-Civil War South drew a significant part of its strength from the same cultural wellspring that fed honor, a deep assumption of the legitimacy of communal authority.

What do you think? Do you see any parallels or potential applications for the contemporary church?