In order to teach the Bible and share the gospel, we do best to understand both how stories work and how people learn. If we lack sufficient knowledge of either, we might create unnecessary challenges to our ministry.

In mission circles, “story” is often linked with orality and UPG work. Among theologians, the entire Bible is frequently described as one grand “Story.” Whoever we are, all people both enjoy but think in terms of story. Story is the brain’s most efficient and natural means of storing and organizing information in meaningful ways.

In mission circles, “story” is often linked with orality and UPG work. Among theologians, the entire Bible is frequently described as one grand “Story.” Whoever we are, all people both enjoy but think in terms of story. Story is the brain’s most efficient and natural means of storing and organizing information in meaningful ways.

Given the storied nature of the Bible, it follows that theology at its best has a narrative framework. This post suggests a practical implication of this observation. This approach simplifies how we think about teaching the Bible and the ease that people grasp our meaning when we present the gospel Story.

Typical Methods

Two major factors typically shape the way evangelicals share the biblical Story.

- TIME SEQUENCE

Of course, time is important. Much teaching follows the sequence of biblical events. Chronological Bible Storying is probably the most famous example of this approach. The advantage of this method is obvious. However, the disadvantage might only become clear with use: It takes a long time to get through the Story. Some story sets get as large as 120 stories.

- THEOLOGICAL SEQUENCE

What if you don’t have time to teach a long list of passages/stories to give a sufficient overview of the grand biblical Story?

In this case, theology determines which stories and ideas are prioritized. The approach ensures that we clearly communicate the main ideas we want to convey. One can get through the Story efficiently. Naturally, theological priorities shape the way one sees how the Bible held together.

Keep in mind that theological doctrines are shorthand markers for ideas found within the larger Story. Before long, we try to find ways to show how various doctrines cohere together. In so doing, we begin to systematize and thus truncate the larger narrative. Although unavoidable at times, the problem comes when we mentally or practically settle for these shorthand summaries.

We can forget that our rending of the Story originates from our choice in theological priorities and might not reflect the inherent plot-line of the Bible.

How we conceive and communicate the grand Story has important implications. Our methods will influence…

- how easily people remember the message

- the stories we select &

- how naturally the Story shapes disciples’ worldviews

How to we tell the biblical Story in a way that best accounts for these concerns?

Building the Story

Good contextualization is both biblically faithful and culturally meaningful. Therefore, our approach account for both text and context.

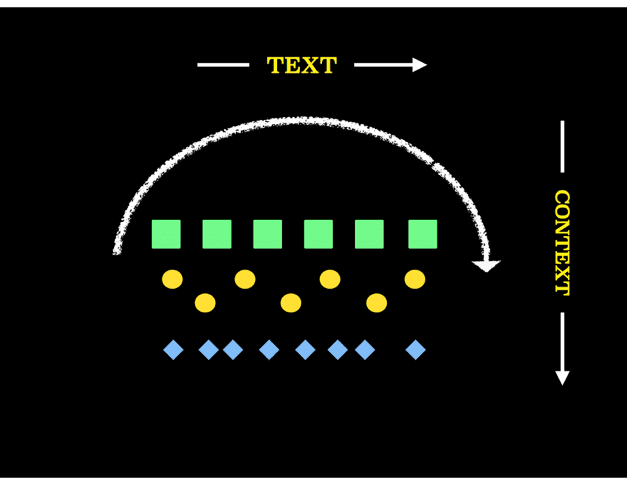

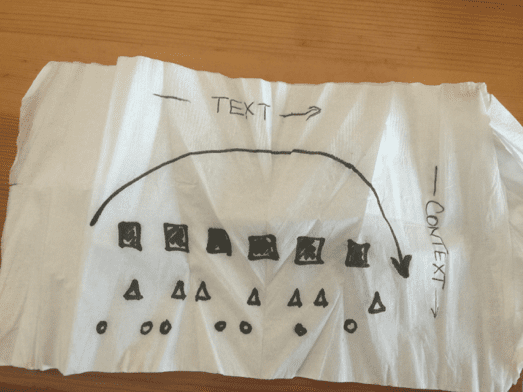

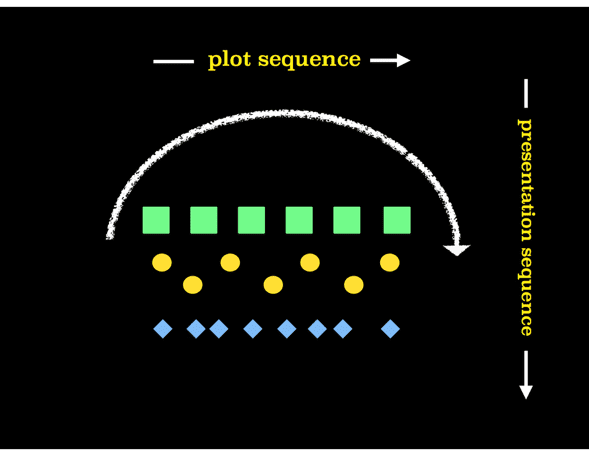

Check out the graph below. Moving horizontally, the text determines the sequence of stories (naturally reflecting the events in the Bible). You can see the teaching stages represented vertically, moving from top to bottom.

1. Text

In stage one, identify 6–7 key stories that already serve as foundational building blocks for the biblical narrative. This is primarily a literary decision, not a theological decision. Like any story, certain passages or scenes are so influential on the overall narrative that the larger story would be irreparably altered without them.

For example, in the movie Titanic, the sinking of the ship is essential. In Star Wars, the use of the force and the relationship between Vader and Luke are basic elements.

In the Bible, a few such examples include the Abrahamic covenant, the Exodus, and the Davidic covenant. Without these three covenants, the Bible ceases to be the book it is.

The story plot in the text determines how we share and teach the Bible.

What is the step-by-step process?

In stage one, we provide an overview of the grand Story according to its inherent plot structure. In stage two, we provide a more thorough telling of the Story, adding appropriate sub-stories and ideas that reinforce the broader framework. Third and successive stages continue the process, adding details that gradually round out the Story.

Notice what happens along the way. When you complete the third stage, you have reinforced the main storyline three times with greater depth. You’ve emphasized primary things and not allowed additional layers to overshadow the broader narrative and its plot movements.

In so doing, we ensure listeners grasp the gospel’s firm framework. In addition, this approach helps us teach the Bible in a balanced manner.

The challenging part is not forcing an alternative story line that is not intrinsic to the Bible at a literary and historical level. One faces the temptation to reshape the narrative to highlight certain theological ideas. Resist the temptation! God inspired the Bible as a Story, not a system (even if our philosophical systems are true).

The basic narrative framework of the Bible naturally gives rise to every theological truth.

2. Context

Every situation, culture and conversation provide a different set of challenges and opportunities. Sometimes we have 10 minutes; at other times, we may have weeks and months to share the gospel and train others. The model I suggest in this post grants us flexibility to handle the spectrum of circumstances.

So, if you only have 10 minutes, you will only be able to share the first layer of foundational stories, i.e. the main plot of the Bible. Ultimately, any and everything we ever talk about from the Bible will elaborate on that grand Story.

As we progress in successive stages, we have greater and greater freedom in selecting which stories and themes we focus on. Of course, the supporting stories and ideas must support the larger framework laid out in Stage One (if not Two).

Yet, the Bible uses a number of motifs to tell the same grand Story. The various images and plot-lines consistently intersect and converge to reinforce the overarching Story of the Bible. Depending on one’s context, different themes and stories will be chosen to communicate the message in a culturally meaningful way. For instance, we might select more passages with honor-shame language. Alternatively, we might highlight family imagery or recount stories that emphasize God’s power.

One Story for All Nations

In effect, the above model applies the observations discussed in One Gospel for All Nations and surveyed on the blog.

The gospel Story consistently uses of two kinds of themes: framework themes (creation, covenant, and kingdom) as well as explanation themes. The latter always shape the firm message the gospel presentation in the Bible. Explanation themes clarify the significance of the gospel and give speakers flexibility when sharing the gospel Story.

With this observation in mind, we can discern how the text itself can and should shape our teaching. Our initial stories set the firm framework on which everything else depends, every story or doctrine that we might share in the future.

Ultimately, we should retell the Story about how the Creator keeps His Covenant promises through Christ, who establishes God’s kingdom among all nations.

This model suggested reflect the firm and flexible model of contextualization we see in the Bible. The Bible frames our approach in two ways.

1. The biblical narrative has an inherent structure that prioritizes certain passages and events above others (in terms of literary influence).

2. The Bible of course determines the sequence of our story. We can’t selectively share passages according to our personal liking.

On the other hand, we have the flexibility we need to engage any cultural context. While framework themes are more prominent in the initial stages, later stages increasingly intersperse various explanation themes. We can choose the best explanation themes to convey a culturally meaningful message.

Final Words

Stories are not systems.

In their way, both stories and systems have an inherent degree of coherency. My proposal suggests that we let the Bible’s inherent Story provide the coherency. This requires taking into account the broader literary context, not simply those passages that prioritize our favorite theological ideas.

Systems are NOT bad. We all make mental models (mini-systems) to serve as short hand for a more complete telling of the truth. Doctrines are merely sign markers. They are true and good in what they affirm, in keeping with their function. They point to a greater reality than themselves.

A system may be true in what it affirms but may not sufficiently allow for certain data. We must be aware that they also tend towards particular dangers. They tend to truncate our message. Compared to the Bible’s inherent structure, systems are more prone to both cultural and theological syncretism.

We all want to teach the Bible in ways that give clarity and are as comprehensive as possible. However, we might be surprised when we take a second look at the Bible itself. How does it achieve that goal? Simply contrast stories and systems and you’ll get the answer.

Stories are more concrete than conceptual.

At times, stories can be ambiguous and might not answer all of our questions. That was ok with God when he inspired Scripture. In the same way, we need to ok with ambiguity that comes with telling the Story of God’s self-revelation in history.

The Bible gives us a firm and flexible approach sufficient for teaching the Bible in any context.