If the LGBT movement has anything, it’s an ironic sense of shame. I’m not talking about sexual morality. I refer to a major reason for the success of LGBT efforts to spur political and social change. They demonstrate uncanny unity in using shame to achieve their goals.

This is one reason people do not listen to the church. Therefore, we ask, “What can the church learn from LGBT about shame?”

The Power of Shame

LGBT supporters effectively utilize the power of shame to silence their opponents. Matters of right and wrong are couched in honor-shame language. Shane Windmeyer, executive director of Campus Pride, spoke against schools that request Title IX exemption,

“The schools on this list have requested Title IX exemption based on religion-based bigotry targeting LGBQ and transgender people for no other purpose than to discriminate, expel and ban them from campus. It is shameful and wrong.”

Political activists proficiently wield the sword of shame. When San Antonio mayor joined a prayer rally mourning the Orlando attacks in June, protestors yelled, “Shame on you, Ivy Taylor!” because she previously opposed a city ordinance supporting LGBT rights. Reports called her “anti-gay.” Nationally, Congressional Democrats adopted this approach as well. When Republicans defeated an LGBT bill, angry legislators waved their fingers and screamed across the chamber, “Shame! Shame! Shame!”

Psychologist Joseph Burgo adds,

“a great many of us have come to view legislators who propose laws that authorize discrimination as bigots and homophobes. We go to our Facebook pages and Twitter feeds to denounce them in the virtual public square; we intend to shame them for their acts of intolerance.”

In this climate, victories are not won through debating issues but by berating opponents.

This liberal use of shame in American society might explain the emergence of Donald Trump as a mainstream presidential candidate. Ezra Klein echoes the sentiments of others when he says,

“Trump answers America’s rage with more rage… Trump doesn’t offer solutions so much as he offers villains. His message isn’t so much that he’ll help you as he’ll hurt them.” He calls Trump’s “complete lack of shame” a political “gift.”

Accordingly, Trump “has the reality television star’s ability to operate entirely without shame, and that permits him to operate entirely without restraint.” As Jack Shafer puts it, Trump’s influence stems from the fact that “You can’t shame a shameless man”

Has the Church No Shame?

Despite these observations, Western Christians are slow to accept shame as a critical theological and moral category. I often hear objections to my own work, which has focused on understanding honor and shame from a biblical-theological perspective. When it comes to the Bible or discussing right and wrong, I’m told we must primarily talk about law and guilt. Shame mainly is an issue for missionaries and pastoral counseling.

By and large, Christians think shame is merely the subjective symptom of a more fundamental and objective problem––guilt. I once submitted an article to a theological journal explaining Christ’s atonement in terms of honor and shame. In response, the editor wrote that the topic was “more of a psychological issue than a linguistic issue.” Many theologians reject understanding sin in terms of shame. To do so, Rafael Zaracho warns, “Morality therefore becomes eminently external and superficial.”

What happens when the church marginalizes shame in favor of guilt?

Christians will find themselves increasing frustrated at the futility of efforts to influence people around them. Shame has returned as the common vernacular for moral conversation in the West. In this context, the church risks proclaiming a true but effectively irrelevant message.

While guilt and innocence are important concepts, they are often secondary concerns in a person’s mind. Consider righteous Job who cried, “Even if I am innocent, I cannot lift my head, for I am full of shame” (Job 10:15; NIV). Whereas guilt says, “I do bad”, shame says, “I am bad.” The latter is more holistic and concerns identity. Honor and shame touch on basic human desires for belonging. When LBGT use shame, the strong emotive force of their appeal drowns out complaints by those in the church.

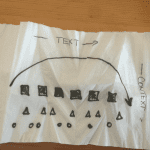

In Part 2, we highlight a few observations to help the church use honor & shame when engaging social issues.