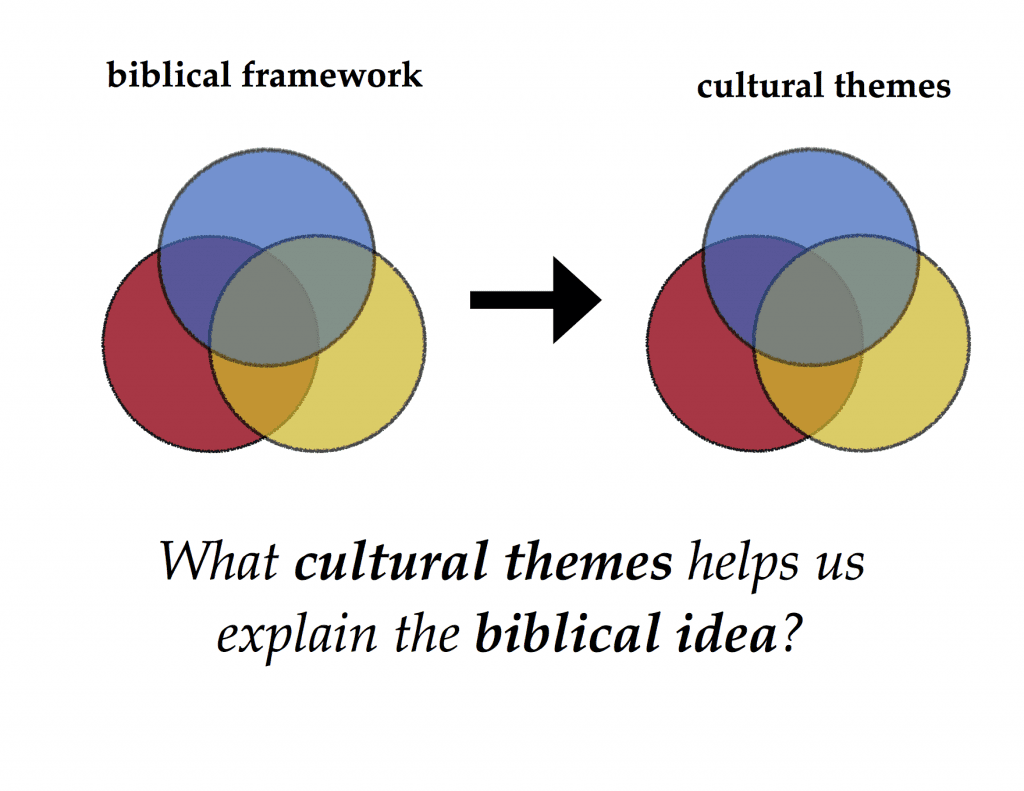

I recently realized that I have never shared on this blog what is probably the most important tool included in One Gospel for All Nations (OGFAN). It is what enables us to contextualize the Bible in a faithful and meaningful way regardless of our cultural context.

Therefore, this post demonstrates how to apply the model of contextualization presented in OGFAN. In order to fully grasp the background that informs each stage of the model, you will need to check out the book. The first two stages in the model provide us with two figures, one representing the biblical text and the second reflecting a cultural context. I will use Chinese culture for the sake of illustration.

The first two stages in the model provide us with two figures, one representing the biblical text and the second reflecting a cultural context. I will use Chinese culture for the sake of illustration.

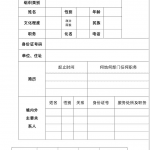

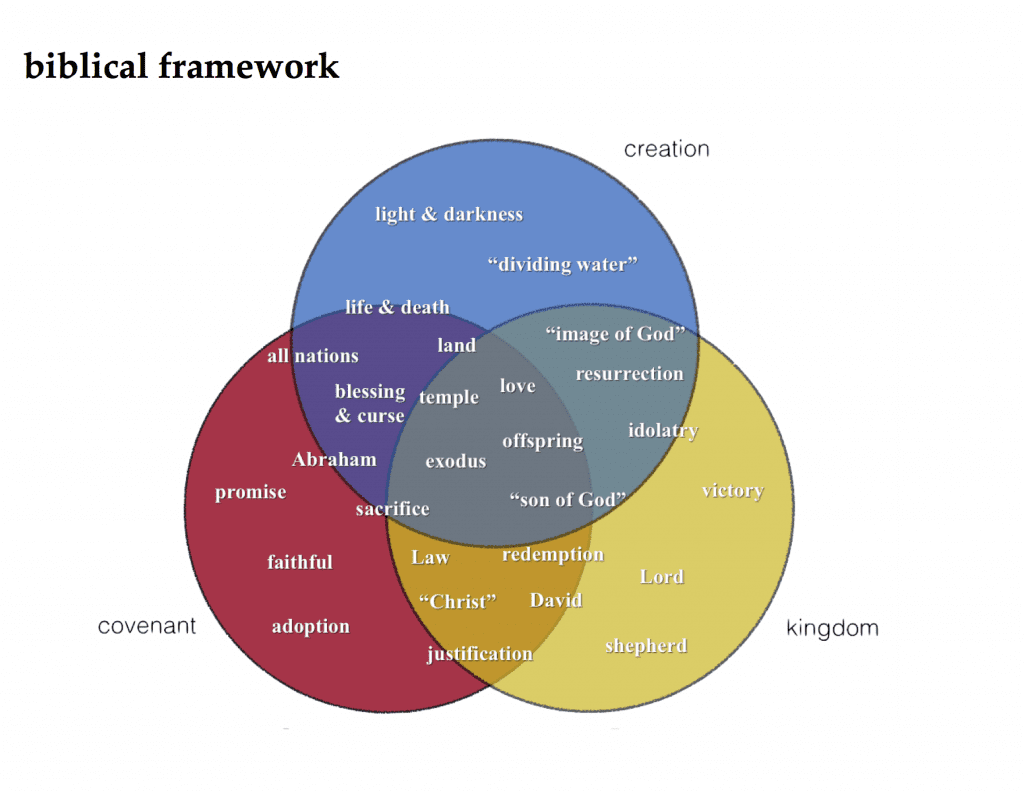

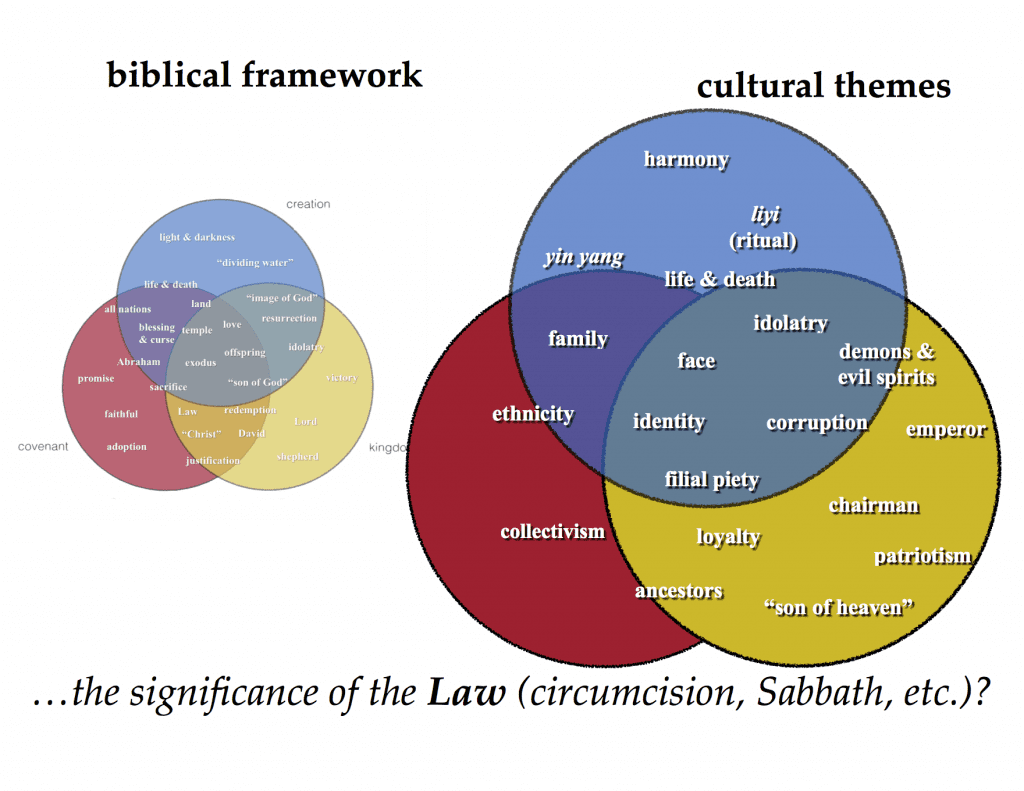

In Stage One, we discern the gospel’s framework themes and explanation themes. The figure below shows how I organize the explanation themes within the three framework themes of creation, covenant, and kingdom. Naturally, the primary significance of some themes cannot be categorized into one circle.

This figure gives us a biblical lens to examine and interpret the culture around us.

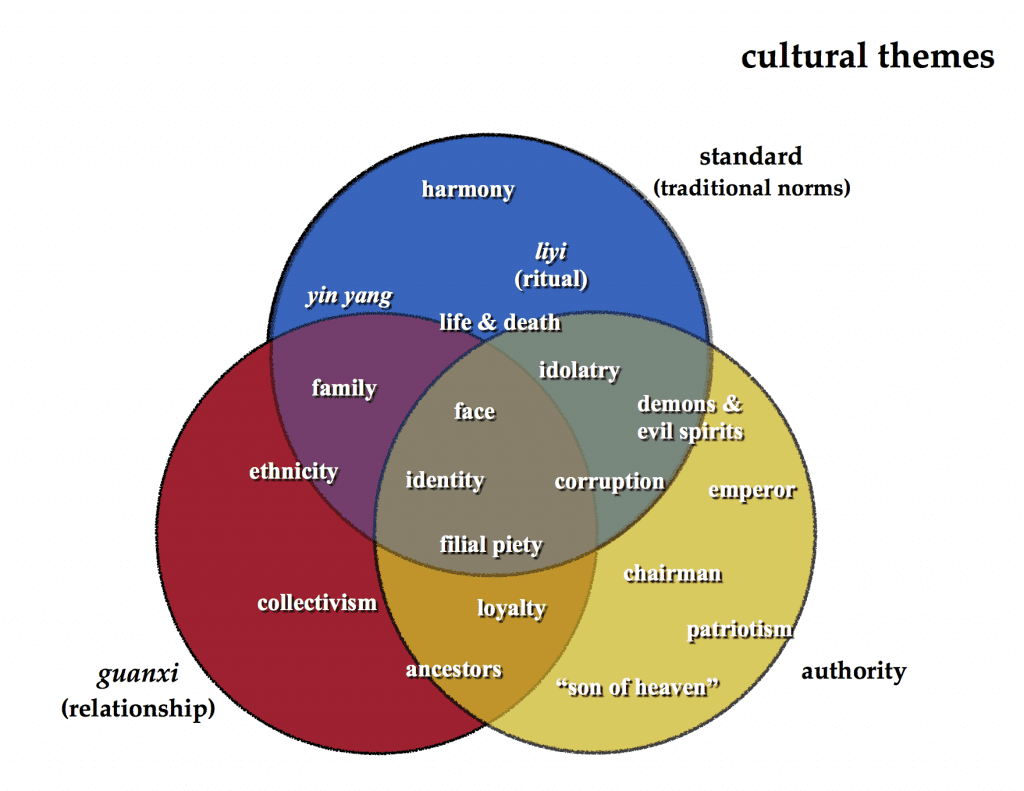

In Stage Two, we identify important themes within our cultural context. What are distinguishing features of the culture or aspects that characterize most people in your context? By looking at history, idioms and familiar stories, a number of themes will no doubt emerge. The figure below gives one example of how someone might depict Chinese culture. Certainly, other details could be added and not every point is unique to China.

The above figure gives us a cultural lens that is fundamentally shaped by Scripture. Beneath covenant is the fundamental idea of “relationship” (guanxi). Authority is the underlying theme of kingdom. A variety of themes resemble ideas associated with creation narratives in the Bible. I have lumped them together under the wording of “standard”, by which I refer to traditional norms and basic assumptions about what is natural to the world.

Use Cultural Context to Explain Biblical Text

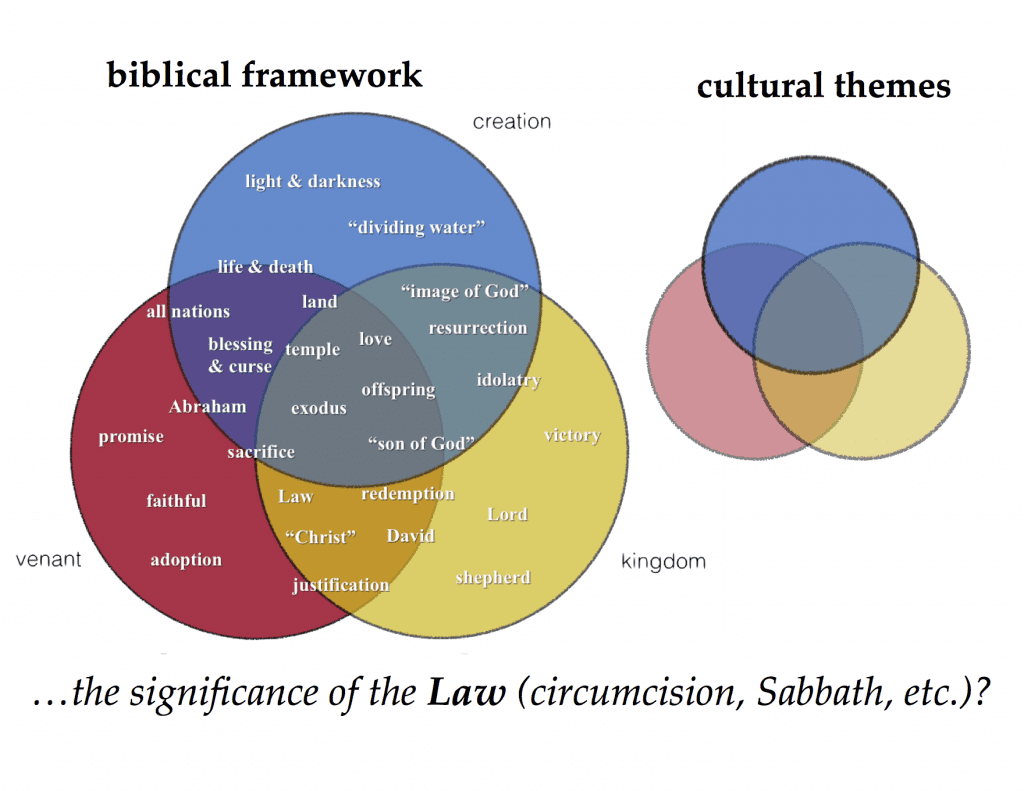

Today I will only address one application of the model: using a cultural context to explain the biblical text. In a coming post, I will move the other direction: from text to context.

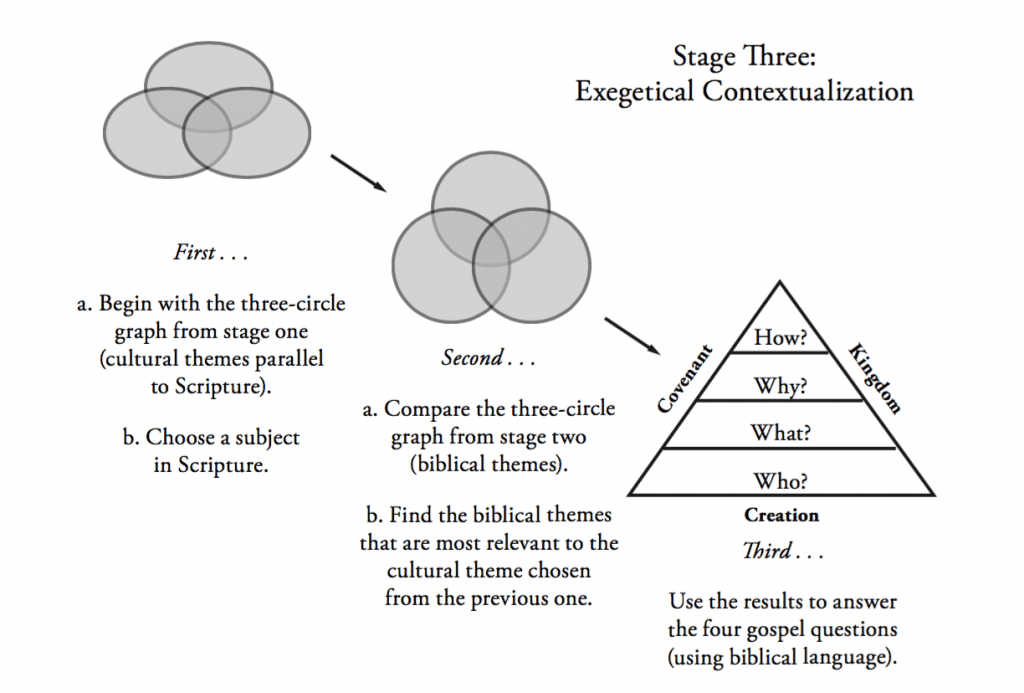

In Stage Three, use the lens from Stage Two to read the Bible. As a result, we are equipped to observe things that are actually in the Bible; yet the gospel’s framework helps is relate multiple facets of culture in a way that prioritizes the issues addressed by the gospel. We do not commit eisegesis, i.e. reading foreign ideas into the Bible. Assume you want to understand the Mosaic Law. Look at the Biblical Framework circles to identify a variety of related motifs, images, and stories. Recall that the graphic can be expanded far beyond what I’ve written.

Assume you want to understand the Mosaic Law. Look at the Biblical Framework circles to identify a variety of related motifs, images, and stories. Recall that the graphic can be expanded far beyond what I’ve written.

The “Law” is found in the overlapping space between “kingdom” and “covenant.” Any of the ideas found in kingdom and covenant will likely be useful for developing a full-orbed understand of the Law. However, those explanation themes that also sit within both circles are probably even better starting points.

At first glance, we note the promise to David that his anointed offspring (i.e. “Christ”) would have an everlasting kingdom. We then recall that Israel’s redemption from Egypt marked God’s election of Israel whereby they would be a royal priesthood and a holy nation. Accordingly, we are reminded that the Law is a royal covenant, not merely a series of abstract Laws governing all humanity. It was a divine gift that distinguished Israel from the nations. Also, justification (as well as righteousness) are frequently associated with royal actions. Refer now to the circles representing cultural themes. A reader’s cultural perspective will invariably influence what he or she notices or overlooks. Every cultural lens has limits and advantages. Having admitted these limitations, we are able to be intentional about putting on another cultural vantage point.

Refer now to the circles representing cultural themes. A reader’s cultural perspective will invariably influence what he or she notices or overlooks. Every cultural lens has limits and advantages. Having admitted these limitations, we are able to be intentional about putting on another cultural vantage point.

A few themes jump out quickly when we look at the overlap between authority and guanxi (relationship).

For instance, identification to the group entails loyalty to the group head. Within the family, this is called filial piety. Collectivistic thinking extends across generations, such that ancestors and cultural traditions bear tremendous authority. One’s identity and “face” is intricately linked to how well a person plays his role within the whole, bringing honor to the group by adhering to insider norms.

Using a Chinese cultural lens, certain ideas become more prominent in our minds.

We are forced to take a second look at practices like circumcision, food restrictions, and Sabbath keeping. Israel’s leaders did not regard these aspects of the Law as mere symbolism; rather, they were judged with as much seriousness as anything that we today were normal see as “moral” in nature (e.g. stealing, murder, etc.).

Israel saw its national identity and well-being tied up in obeying God who gave the Law. Keeping the Law determined who was reckoned a Jew (or who would be cast out like a Gentile). Time and again, following the Law devolved into little more than maintaining cultural customs and honoring ancestral traditions.

Given Israel’s turbulent history and exile, the Law was an important means of protecting the nation’s purity, a way of expressing allegiance to God their true King. Their worship to God was simultaneously an act of rebellion against Caesars and all Gentile colonizers. Naturally, those who were loose with the Law would be viewed with suspicion by many Jews, who might take measures to shame wayward persons into conformity.

In One Gospel for All Nations, I call Stage Three “exegetical contextualization” because contextualization begins with interpreting the Bible.

All interpretation is an act of contextualization.

A Chinese Perspective on the Bible

The Bible is not inherently Chinese yet many Eastern ways of thinking resemble those found in the Bible. Using a Chinese lens, we can better appreciate the significance of debates in the NT concerning Abraham, Law-keeping, and the division between Jews and Gentiles.

Traditional Western readings tend to minimize underlying cultural dynamics and instead generalize the Mosaic Law as though it were a universal moral law. Interpreters then oversimplify the problem Paul addresses to that of mere legalism, trying to merit salvation via keeping God’s rules.

By using a view that is more East Asian than Western, we at least become aware of potential readings and issues that need further exploration. We recognize that the biblical teaching might not be as simple as we first thought. Not everyone else in the world asks our questions or has our struggles.

Instinctively, we all draw from our own experiences when reading ancient documents. Given the dangers of a mono-cultural worldview, reading the Bible through other cultural lenses gives us new access to topics and questions that are both global and potentially ancient.

In a coming post, I will show how to apply the model in the opposite direction, moving from the biblical text to cultural context.