Few books simultaneously entertain, provoke, challenge and instruct. A recent IVP book by just that. It’s called Paul Behaving Badly: Was the Apostle a Racist, Chauvinist Jerk? (E. Randolph Richards and Brandon O’Brien). The authors previously collaborated to write one of my favorite books Misreading Scripture with Western Eyes. This work has a similar feel to their previous book.

You know all those secret thoughts you’ve had about Paul but weren’t willing say out loud? Well, Richards and O’Brien put them on the table and address them head on. Here are some of the chapter titles.

You know all those secret thoughts you’ve had about Paul but weren’t willing say out loud? Well, Richards and O’Brien put them on the table and address them head on. Here are some of the chapter titles.

1 Paul Was Kind of a Jerk

2 Paul Was a Killjoy

3 Paul Was a Racist

4 Paul Supported Slavery

5 Paul Was a Chauvinist

6 Paul Was Homophobic

7 Paul Was a Hypocrite

8 Paul Twisted Scripture

Each chapter lays out a charge against Paul. But what is surprising (and so good) about their approach is this: they actually take the accusation seriously. As in their previous book, they often show how we easily misread Paul because of our contemporary perspective. While it is vogue to say Westerners have limited perspectives on the Bible, it’s quite another thing to have examples put in front of you. The authors are humble and gracious in the process.

Also, Richards and O’Brien provide simple explanations and key insights concerning Paul’s ancient context. In so doing, they frequently add an ironic twist by showing how Paul indeed behaved badly,…according to the judgment of his contemporaries. Nevertheless, he adapted to each situation in keeping with the Spirit.

A Practical Approach to Ethics

My favorite chapter? “Paul was Homophobic”. First, they helpfully re-frame the entire issue, reminding us that first century people used different categories and asked different questions than we are. Rather than talking about “gay,” “straight,” and “orientation”, ancients discussed penetration, being penetration and the sexual exploitation suffered by slaves.

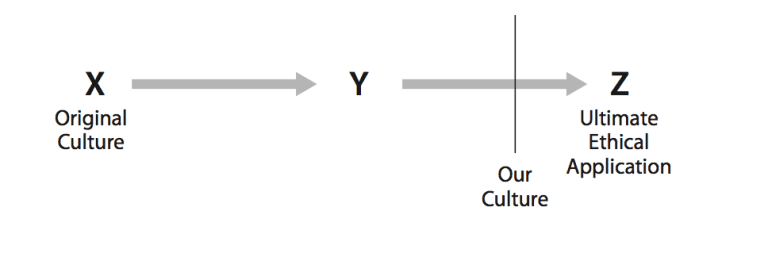

Most significantly, the author’s suggest we use a “trajectory hermeneutic” to understand how Paul’s comments about homosexuality (among other issues) both relate to his context and yet correct local norms.

Here is a summary illustrating how to apply a “trajectory hermeneutic.”

First we determine how the broader culture(s) of Paul’s day viewed an issue (X). Then we compare to that perspective the teaching of Paul on the subject. Next we have to ask if Paul’s teaching (Y) represents the outer extent of the trajectory, or if God intended the teaching to continue to grow (like yeast). Webb says if Scripture intended us to move beyond “Y, ” then there will be a “seed” in the text, an idea that moves beyond the “Y” and points toward “Z,” the ultimate or ideal ethic. (138)

As a result, Paul does not go as far in his corrections as many would prefer.

This perspective is instructive for anyone trying to discern the Bible’s teaching on countless contemporary matters. It reminds me of Jesus’ comment that God tolerated divorce under the Mosaic Law because of people’s hard hearts (Matt 19:7–8). While God hates divorce, his Law initially mitigates its negative consequences. A similar argument could be applied to polygamy. When Christ comes, restrictions are tightened, not loosened.

There is a lesson for us here. The church might need to rethink how we challenge the ethical behaviors and assumptions of those around us. Perhaps we need to seek solutions that merely make progress towards an ideal and rejoice more in small victories. An all or nothing attitude might be counterproductive.

Lost from the Start?

How often do we 输在起跑线上 (lose at the starting line)?

The book consistently challenges readers to re-examine their initial questions and basic assumptions. Ask yourself, “What is another way that someone might consider this issue?”, even if some possibilities sound strange to us.

As I remind my students, the Bible does not always answer OUR questions. If not, perhaps we need to rethink our questions and discern the fundamental issue that underlies our problem. Don’t force our terms and definitions into Paul’s context.

Their chapters on racism and slavery are excellent examples. Not only do the authors rigorously focus on the biblical text, they demonstrate keen sensitivity to nuance but without succumbing to endless speculation. For example, they distinguish the meaning and strategic use of the term Ioudaios (Judean), which denotes a subset of Jews and not all Jews. Paul does not slander “Jews” in broad anti-Semitic strokes. Also, they remind readers that “insiders” can get away with saying things that outsiders cannot; accordingly, we can’t impute ill motives and intentions onto Paul. Elsewhere, Paul uses a stereotype of Cretans (Tit 1:12) to “rattle them by implying that in this instance they are validating the stereotype” (86).

In short, since the ancient world did not think of “race” (or slavery”) in the same way as modern readers do, you can’t expect Paul to respond in a way that naturally makes sense to us. Likewise, we should not think someone can apply Paul’s words to contemporary ethical issues without concentrated study and self-examination. If we try to bypass the process, it will be us who behave badly. And we can’t blame Paul for our misapplication.

This book is excellent for spurring conversations with friends, family and in small groups. The basic approach is constructive and practical. I’d love to hear what you think of their specific conclusions. Drop a comment with your thoughts.