If you ever sang “Take my Life” in church, you have probably been taught that “ holiness ” refers to a moral condition, a state or moral purity that reflects God’s unique character. Accordingly, you were taught Lev 19:2, “Be holy because I, the Lord your God, am holy.”[1]

However, both the Hebrew and the Greek Septuagint of Lev 19:2 use indicative, not imperative, verbs. In other words, you are holy because I, the Lord your God, am holy. In The Lost World of the Israelite Conquest , John and Harvey Walton suggest that Lev 19 makes a statement of fact, not a command.

But let’s not get ahead of ourselves and import the New Testament into the Old Testament. Did Israel need holiness? Could ancient Jewish youth have sat around the fire singing,

Holiness (Holiness) is what I long for.

Holiness (Holiness) is what I need.

Holiness (Holiness) is what You want for me

Tradition is not Wholly True

The Waltons explain the problem with common views about holiness and cleanliness in the Bible.

Concerning “holy”:

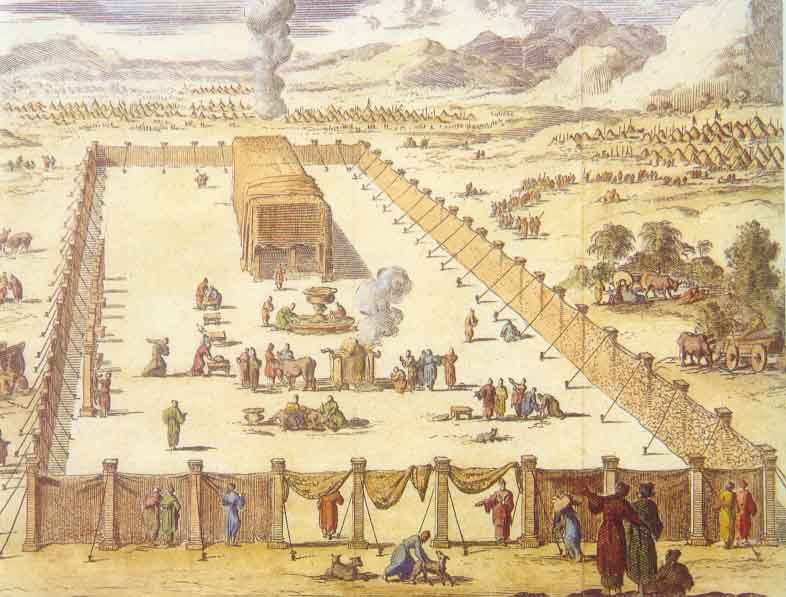

The problem with this specific interpretation is that the word translated “holy” (Hebrew root qdš) cannot possibly mean “having a certain moral character.” The vast majority of things designated as holy are inanimate objects such as the ark, the altar, and the lampstands for the tabernacle. …The only persons (potential moral agents) designated as a holy thing are the priests, but this is never interpreted to imply that the priests are more moral or have a different moral character from the rest of the assembly. (p. 105)

Concerning “clean”:

The concept of cleanliness is connected to the idea of suitability for cultic ritual use or participation. Clean (ṭāhôr) cannot mean “moral” for the same reasons that “holy” (qdš) cannot; many unclean actions are not sinful (menstruation, attending a funeral), and many unclean things have no moral agency (animals, molds, locations).

Cleanliness is tangentially related to immorality in the sense that sin (as immorality) is one possible cultic contaminant, but impurity (ṭūmʾâ) and immorality (e.g., ḥaṭṭāʾt) are in no way interchangeable. Humans can make themselves clean or unclean, but holiness is a status that is conferred by God. It cannot be earned or acquired (or lost) through behavior. (pp. 106-107)

So, if the Waltons are correct, which I think they are, then we can easily see how easy it is to confuse part of the truth for the whole of the truth.

(In this series, click for Part 1, Part 2, Part 3)

What then is holiness?

To be “holy” means to be identified or associated with God. Therefore, God does not and cannot demand holiness of people. Why?

Holiness is a status. It is granted, not earned nor related to moral performance.

What does this mean concerning the conquest of Canaan?

since holiness refers to co-identification with deity and is not to be equated with morality or with meeting standards of cleanness, no one, neither Israelites nor Canaanites, can be guilty of not being holy. (p. 117)

The nation of Israel is reckoned holy, even if individuals were not morally upright.

As a conclusion, let’s relate holiness back to the previous point about the Law’s purpose.

“the purpose of the holiness code is to define order; more precisely, however, its purpose is to define the order that specifically defines the nation that defines Yahweh.” (p. 120)

Ancient Text for Modern Contexts

I know some readers will be tempted to dismiss this book simply because it sounds too strange or different from tradition. But I would urge you to not to do that for two reasons.

1) Tradition must never trump Scripture.

2) The Waltons give close attention to the biblical text such that any disagreement ought to be based on their handling of the text, nothing else.

I surmise this book will cause us to adjust and rethink various and subtle ways we teach the Bible in cross cultural contexts. I expect that a more biblically and historically faithful reading of the text will better connect with non-Western cultures.

[1] Peter’s application of Lev 19:2 often confuses people. In 1 Peter 1:15–16, he writes: As obedient children, do not be conformed to the passions of your former ignorance, 15 but as he who called you is holy, you also be holy in all your conduct, since it is written, “You shall be holy, for I am holy.” Peter does add “in all your conduct” and bases the command on the indicative in v. 16.