The following guest post comes from a missionary, “David”, who serves in a location that cannot be disclosed due to security concerns. He and his wife are white but have an adopted black daughter.

Our family was engrossed in a family night movie when I barely hear my daughter’s soft voice ask, “What’s a n*gger?” A part of me would rather have the sεχ talk or explain what m@stvrb*tion is. But that’s not my wife and I signed up for when we adopted her years ago.

An Out of Culture Experience

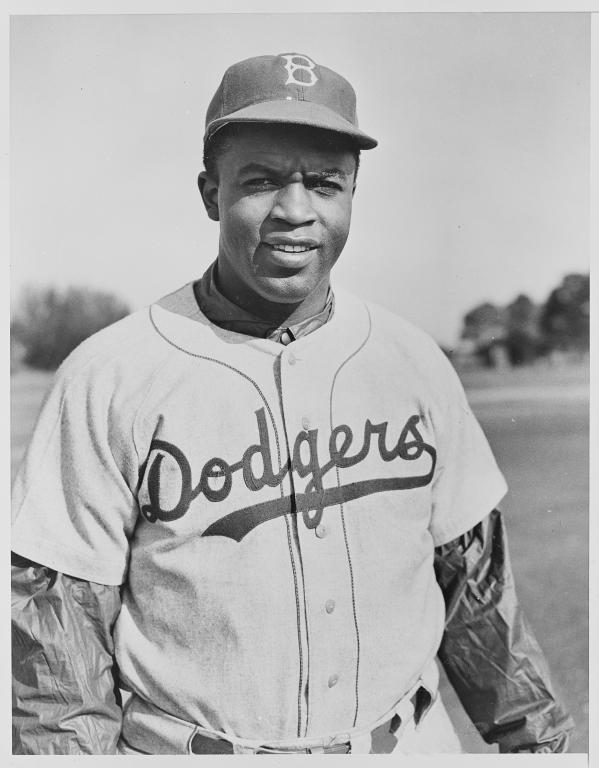

We were watching 42, a movie based on the true story of Jackie Robinson. He was the first black player to play in major league baseball when in 1947 he joined the Brooklyn Dodgers. The movie is PG-13 because of the subject matter and racial slurs. Ever since she was little, we’ve been very open about her background. We’ve celebrated figures in black history and watch Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech every year on MLK Day.

We don’t live in America. We live overseas as missionaries. Our family stands out from the people around us, especially with our being white parents of both white and black kids. We all have American passports, but nothing in our daily lives naturally leads us to think about America’s history and race conflicts.

She is a TCK (“Third Culture Kid”), which means she is neither fully the culture of her parents (her mother and I) nor that of the place we live. She is a mix of both. At the same time, we are well aware that she will likely spend much or most of her life in the United States. When she lives in the States, she’ll inherit a cultural history that is otherwise foreign to her own experience. Where we live, people are curious when they see her. Some local people have never seen a black person except perhaps in a movie or on TV. Still, they treat her with kindness and respect.

As parents, we face a delicate problem. How do we make her aware of America’s problems and past without instilling fear in her as though nothing had changed since the 1860s? How do we prepare her for the fact she could face prejudice by certain Americans but not infuse in her an unhealthy victim mentality?

We’ve recently expanded the range of movies we allow our kids to watch. By doing so, we’ve increased the amount they’ve been exposed to more serious social issues, like racism. In 42, as you’d imagine, haters of Jackie Robinson call him ever disgusting thing you could think of, and probably worse than you might think.

“What’s a nigger?”

When I heard her ask the question, it felt like one of those movie moments when everything goes silent in your mind. Somehow 30 minutes of flashback and hypothetical conversations fly through one’s mind in a span of 0.8 seconds. I immediately got up and paused the movie. I had no idea what exactly what I’d say. I knew this day would come, but we hadn’t formulated a packaged speech.

I returned to the couch and asked her to repeat her question so that everyone could hear it and, in part, to give me a few extra seconds to figure out what I’d say. Here is a rough summary of what I said.

The word “nigger” is a mean name people used to call black people. The term originally referred to people who didn’t know stuff. People thought black people didn’t know things. You know how people, for some reason, call others by names just to be mean? Through history, groups have been mean to each other. French didn’t like English people. Germans didn’t like Russians. Chinese haven’t like Japanese. Kids at school do this sort of thing too right? And so, one thing people do in those situations is call people names. It’s not just black people who get called names.

People used to call Jews “kikes,” Mexicans were called “spics.” Italians, people from Italy, was called “wops.” I have no idea what that even means. So, in the past, people used to call black people “nigger.” It’s sad, but this kind of thing has happened all over the world throughout history.

But today, we never want to use that word. Does that make sense?

She just sat silent, listening intently to each word. No one moved or interrupted when I paused. She has seen kids treat one another in mean ways and has seen bad people depicted in movies. She was not especially alarmed. She didn’t express any personal offense or anxiety. If anything, she expected confusion and sadness that someone would be so cruel to other people.

God hates hate. Period.

One of my hopes in answering the way I did was simply to properly frame the issue of black-white racism. Racism exists everywhere, not just America. And it’s evil everywhere, not only in America. God detests hatred even when it doesn’t make the news.

When I first began to learn the local language as a missionary, someone once asked, “Do you know what the hardest language is to learn?” I guessed Japanese, Chinese or Arabic. “It’s whatever language you are learning now at the moment.”

In the same way, we tend to think the problems we see or experience are the absolute worst there are. It certainly feels that way. But racism or something like it exists everywhere else too, whether in the Middle East, Asia, and Africa.

Hatred and ignorance are parts of the human problem. At any given moment, it could be said that we are both oppressed and oppressors.

When we focus on only one form of hatred, it’s possible that we create a host of other problems. We risk conjuring an unhealthy paralyzing fear and reciprocal hatred that makes reconciliation virtually impossible. Also, we might unknowingly excuse other types of racism and sexism. We could easily overlook or minimize other prejudice that exists around us or in our own hearts.

I answered my sweet daughter as I did not because I want to minimize the deplorable treatment of black people in American history. Rather, I want her to hate all forms of injustice with right disgust. I want her resolute in opposing evil in every manifestation, not only the kind that affects people who look like her.

That night after the movie, when everyone else went to bed, I could not sleep. I empathized with the feelings that she could have had if she knew more personally the gravity of her question. For generations, black kids found out from hard experience what was meant by words like “negro” and “nigger.”

Because of heroes like Jackie Robinson, she was fortunate to learn by asking her dad, “What’s a nigger?” And for that, I’m grateful.

A Final Comment from Jackson Wu

I wanted to post David’s story for multiple reasons, several that concern many themes discussed on this site.

I’ve seen the movie 42. So, in light of the above post, I decided to look up some dialogue I recall from the movie. During the opening scene, the Dodgers’ owner has a conversation with two of his assistants.

The following comes from the screenplay.

BRANCH RICKEY

I’m going to bring a Negro ballplayer to the Brooklyn Dodgers.

HAROLD PARROTT

With all due respect, sir, have you lost your mind? Imagine the abuse you’ll take from the newspapers alone. Never mind how it’ll play on Flatbush. Please, Mr. Rickey.

BRANCH RICKEY

There’s no law against it, Clyde.

CLYDE SUKEFORTH

There’s a code. Break a law and get away with it, some people think you’re smart. Break an unwritten law though, you’ll be an outcast.

It’s the last line that I find so powerful. Sukeforth articulates a significant insight about honor and shame. We often think of morality merely in terms or rules: “Do this. Don’t Do that.”

But Sukeforth speaks of a “code,” and “unwritten law,” that governs people’s hearts. This code dictates what is deemed honorable or shameful. This code is often unconscious. And for that reasons, we must be diligent to discern its impact on lives and community.