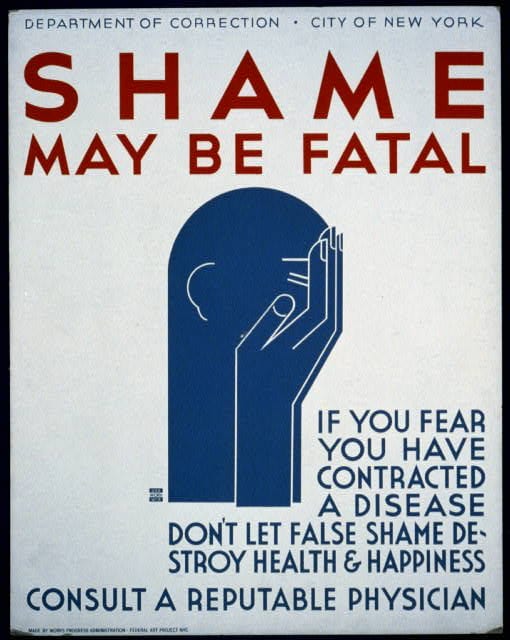

For so long, Christians have tried to conjure a guilty conscience in the minds of those who hear the gospel. Until recently, few people typically spoke of shame and evangelism in the same sentence. This is unfortunate because shame is a far bigger obstacle to people coming to saving faith than are guilt feelings.

In this post, I explain three reasons that shame fosters inaction and hinders people from changing in their lives.

Why Shame Kills Change

-

Fear

Shame concerns a person’s identity, not only one’s actions. It leaves an indelible mark on a person. Shame says, “I am unworthy of love.” It so scars the heart and mind that a person defines him or herself by that sense of shame.

Consequently, shame instills fear. It whispers, “I cannot change. I will always be unworthy of others’ acceptance.” Why?

A person in the throes of shame experiences waves upon waves of memories that reinforce the belief that they will always be a flawed, unlovable person. Every glimmer of hope and opportunity for change is tamped down with another memory of failure or rejection.

Guilt focuses on wrong-doing. We can isolate behaviors. Wrong actions can be corrected. We can often make reparations. But how do we rectify the problem when the problem is “who we are”?

-

Grief

Shame produces grief and regret. A person feels such intense grief that he cannot bear to face the reality of his wrong-doing. Why would one want to look back to reflect on the cause of one’s shame? Doing so would only intensify further the pain of one’s past.

As a result, a habit of denial emerges. The mind finds excuses and forges them into reasons. By adding a little rationality, the mind reconstructs the past such that repentance and genuine remorse become difficult and, in some ways, virtually impossible. This is one strategy we use to hide shame.

How else do people hide their shame?

June Price Tangney, in her seminal book Shame and Guilt, identifies two of the most common responses to shame––withdrawal and blame. Certainly, blame could be misplaced, a way of dodging responsibility. But not always. In reality, shame quite often is the consequence of several people’s sin, not one person’s alone.

-

Anger

Tangney mentions another effect of shame. She writes,

“externalized blame can serve to reduce painful awareness… the accompanying feelings of self-righteous anger can help the shame person to regain some sense of agency and control. Anger is an emotion of potency and authority. In contact, shame is an emotion of the worthless, the paralyzed, the ineffective.” (p. 93)

Anger is a secondary, derived emotion. It stems from fear and the felt need to protect oneself.

Ironically, such anger perpetuates problems. Those who are enslaved by shame alienate other people. Relationships are poisoned. Family and friends distance themselves from the angered individual, whose anger prevents others from showing them compassion.

Shame thus creates a vicious cycle. Shame manifests as anger. Anger divides relationships and perpetuates a sense of isolation. The world seems to confirm a shame-filled person’s fear that they lack worth and will never find a place to belong.

Allow Shame to Adjust our Approach

As I mentioned in my previous post, evangelism seeks to evoke more than guilt feelings. When a person sees a pattern of sin and one’s alienation from God, shame is the natural response. This is why I hope many people will listen to Chris Flanders’ EMS presentation.

Yet, we must be mindful to know shame’s potential for destruction. Fire has its use when it stays within proper boundaries. In the same way, shame both destroys people and leads them to repentance. We need a right sense of shame. A shameless person is to be despised. This balanced perspective of shame is evident throughout the Bible.

I hope you will consider how you have understood shame and how that understanding affects your own ministry.