There is an internal logic to shame. This is one reason Te-Li Lau writes Part 1 (“Framework”) of Defending Shame. For many people, the initial section of an academic book could easily be called “Boring But Necessary.” I was tempted to skim the first few chapters of Lau’s book; I’m glad I didn’t.

(The first post in this series gave a broad introduction to Defending Shame: Its Formative Power in Paul’s Letters.)

Definitions and Clarifications

Chapter 1 provides the conceptual framework for his project. In general, Lau defines shame as “the painful emotion that arises from an awareness that one has fallen short of some standard, ideal, or goal” (p. 29). While I might quibble with a few minor points, this introduction is standard for any such work on honor and shame. Most importantly, he makes several important clarifications that shape the rest of his work.

Occurrent experience of shame

“the discomforting and painful emotion that arises when one is aware of certain inadequacies of the self under the gaze of an other.” (p. 24)

Dispositional shame

“(sense of shame or shamefulness) is the disposition, inclination, and inhibition that restrains one from pursuing certain actions from pursuing certain actions that are shameful without implication that shame is actually being experienced by the person.” (p. 24)

Retrospective shame

“a kind of shame that is consequent upon having done bad acts (either in the past or present)” (26)

Prospective shame

a kind of shame that “looks to the future and restrains one from pursuing bad acts.” (26)

Acts of shaming

“what and individual or collective agent does to bring about the occurrent experience of shame in an individual or collective group.” (26)

Simply being aware of these distinctions will make a big difference in thinking through the implications of honor and shame. In chapter 2–3, Lau surveys the Greco-Roman and Jewish backgrounds respectively.

Greco-Romans Background

Why study ancient Greek and Roman perspectives concerning shame?

First, this is the cultural milieu in which Paul and his readers lived and learned. His study introduces important terms and distinctions that modern readers likely miss due to the vagueness of contemporary shame language (especially English). Second, Lau’s study sheds light on the inner logic governing honor and shame, whether in history and/or across cultures.

The ancient Greeks, like Chinese philosophers, clearly saw shame as a moral emotion. In fact, unlike many people today, they did not dichotomize justice and shame. For example, Protagoros (a pre-Socratic philosopher) taught that the second stage of civilization is where “Zeus intervenes in human history with his two gifts: justice (δικη) and shame (αιδως)” (34). Shame regulates behavior such that Democritus says, “Learn to feel shame (αισχυνω) in your own eyes much more than before others” (36).

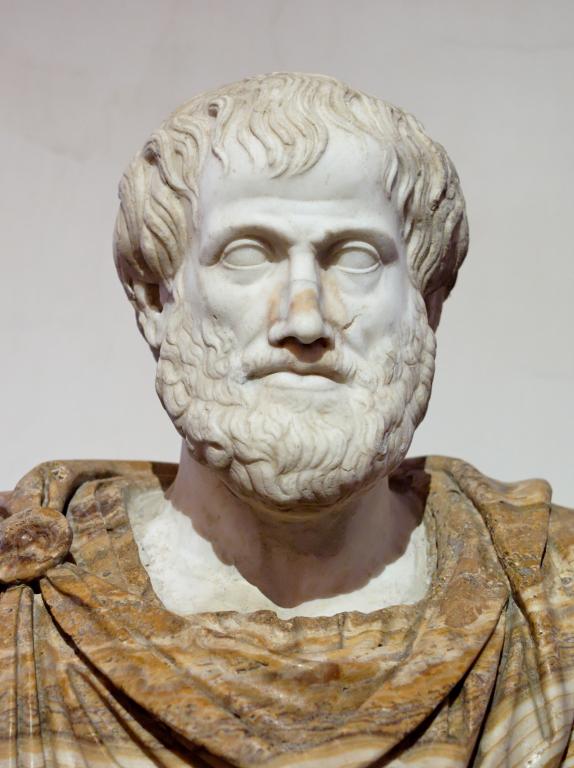

Aristotle explains shame in this way.

“Let shame then be defined as a kind of pain or uneasiness in respect of misdeeds, past, present, or future, which seem to tend to bring dishonor; and shamelessness as contempt and indifference in regard to these same things.” (Rhet. 2.6.2)

Shaming refutation, Lau suggests, was and is an important tool for moral formation. In my own words, I summarize a key take away like this: to shame others (for the sake of ethics) is akin to showing people what they could be and so evoke disgust. Shaming someone need not be a definite, once-for-all negative assessment of another’s worth. Shame is integral to a fully functioning conscience.

There are so many more things that deserve attention. For now, this must suffice.

Jewish Background

Lau’s reflections on shame in ancient Israel are equally substantial. The chapter draws from both biblical and extra-biblical texts. He rightly observes the way Jewish writers use metaphors to convey shame and honor (e.g., clean, unclean). Blessing and curse likewise carried honor-shame connotations. Shaming actions served as sanctions for behavior.

Wisdom helps us discern between various types of shame. A quote from Ben Sira highlights a key distinction. He says,

“there is a shame that leads to sin, and there is a shame that is glory and favor” (83).

Ancient Jewish writers exalted in the glory of God’s power and faithfulness; they pointed to moral exemplars who honored the Lord. Yet, they were willing publicly shame those who veered from the Lord “with the hope that they might be able to perceive their actions from the perspective of the community” (89).

_______________________________

The next post looks at Part 2, where Lau interprets Paul’s letters. For now, here’s an excerpt of Defending Shame.