Few things perplex and upset Westerners more than an honor killing. Of course, there are good reasons people find the practice deplorable. (Given my previous article, it seems fitting to repost this one, which originally appeared on Scot McKnight’s JesusCreed.)

In recent years, reports of honor killings have become far more common. For example, click here, here, and here. An honor killing occurs when a person does something deemed shameful by one’s family or village. Typically, they involve a woman who is accused of illicit sexual relations with someone with whom she is not married. In order to restore honor to the community, a relative––often a brother or uncle–––will then murder the woman. Only then will their wrath be appeased.

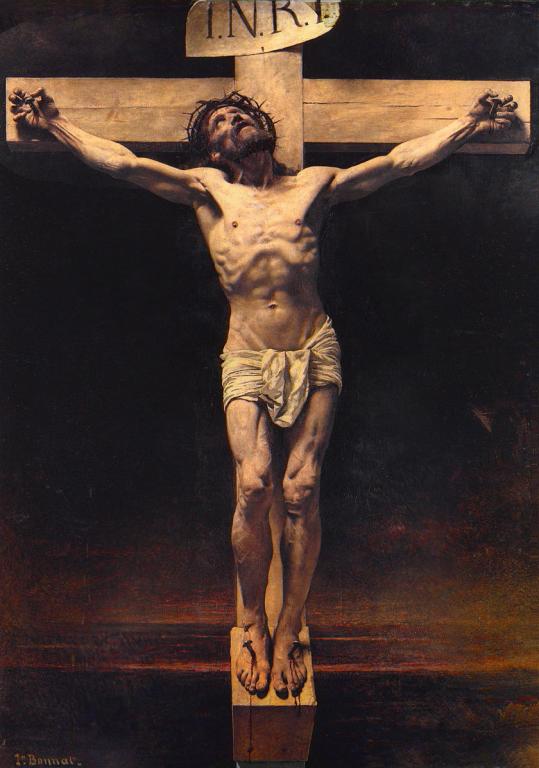

So, it’s not surprising how people respond when they hear me and others talk about the importance of honor and shame in the Bible. They ask a very natural question, “Was Jesus’ death an honor killing?”

Unreasonable question?

The very idea of explaining the cross with something so heinous as an honor killing is revolting to most people. Yet, I’ve heard some people suggest the possibility that we could explain penal substitution in terms of an honor killing. Before dismissing the question, consider how people might potentially link these ideas.

What similarities might they share? In each . . .

- A father is dishonored by the shameful behavior.

- The offense evokes his wrath.

- To appease his wrath, the father seeks to avenge the affront to his honor.

- Consequently, the father punishes his child, upon guilt has been imputed.

The above four statements generally resemble traditional accounts of penal substitution. It doesn’t take a lot of imagination to understand why some people reject this theory of atonement. They think of it in the same way that people think of modern-day honor killings.

How does God judge the cross?

To the relief of many readers, I do not recommend we call Christ’s death an honor killing. The comparison is not helpful. However, the entire question does reveal quite clearly the significant questions at stake when it comes to the matter of contextualization. I don’t commend it as good contextualization.

To begin, the association between the cross and honor killings would cause more harm than good. Due to the confusion of concepts, using terms like “honor killing” is not helpful. For one thing, people do not associate an honor killing with love, but rather with vengeance alone. Let’s be clear––the biblical writers pinpoint those responsible for his murder.

Peter says to those in Jerusalem,

“this Jesus, delivered up according to the definite plan and foreknowledge of God, you crucified and killed by the hands of lawless men. [Yet] God raised him up, loosing the pangs of death, . . . ” (Acts 2:23; cf. 2:36; 5:30; 10:39; Luke 24:20).

The Father loves the Son. His murderers hated him.

It’s better to speak of Christ’s work on the cross as an “honor death”, not a “killing.” As such, he willingly sacrificed himself for the sake of God’s honor (and ours). I’ve argued the latter idea more thoroughly in my first book Saving God’s Face: A Chinese Contextualization of Salvation through Honor and Shame.

This is a far more faithful depiction of the cross. Among the many passages we could choose from, consider these two:

And walk in love, as Christ loved us and gave himself up for us, a fragrant offering and sacrifice to God. (Gal 5:2)

All this is from God, who through Christ reconciled us to himself and gave us the ministry of reconciliation; that is, in Christ God was reconciling the world to himself, not counting their trespasses against them. (2 Cor 5:18–19)

Christ was certainly killed, . . . by murderous sinners. Through Jesus’ death, God indeed vindicated His honor (foreshadowed in Ezek 36:22, 32). Nevertheless, Christ gave himself.

Implications of an “honor death”

The shift in perspective has significant practical implications. In fact, seeing Christ’s work as an “honor death” actually undermines the type of thinking that fuels so-called “honor killings.” From the perspective I’ve suggested, people can’t mistakenly think they imitate God by murdering a relative who has publicly shamed them.

On the one hand, God does not in fact smite humanity in vengeance; he instead took on flesh. That is, he “emptied himself, by taking the form of a servant, being born in the likeness of men. And being found in human form, he humbled himself by becoming obedient to the point of death, even death on a cross” (Phil 2:8-9).

On the other hand, Christ’s death spurs his followers to do the opposite of anything that might be called an “honor killing.” Consider how the cross-shaped Paul’s approach to ministry.

But we have this treasure in jars of clay, to show that the surpassing power belongs to God and not to us. We are afflicted in every way, but not crushed; perplexed, but not driven to despair; persecuted, but not forsaken; struck down, but not destroyed; always carrying in the body the death of Jesus, so that the life of Jesus may also be manifested in our bodies. For we who live are always being given over to death for Jesus’ sake, so that the life of Jesus also may be manifested in our mortal flesh. So death is at work in us, but life in you. (2 Cor 4:7–12)

In effect, Christ’s death redirects our path to glory. He overturns conventional notions of honor and shame. Accordingly, the writer of Hebrews exhorts his readers to look to

Jesus, the founder and perfecter of our faith, who for the joy that was set before him endured the cross, despising the shame, and is seated at the right hand of the throne of God. (Heb 12:2)

In the same way, we Christians need to rethink our conceptions of honor and the way we seek honor. I particularly have in mind passages in 2 Corinthians, Hebrews, and 1 Peter. I’d urge people to reflect on the way each letter reorients honor and shame in light of the cross.

When we present Christ’s death in this way, we magnify the glory of God. Without calling the cross an “honor killing,” we can contextualize the gospel message in a way that is biblically faithful and culturally meaningful.