How does one begin to sort how honor and shame infuse Christian nationalism?

We must first recognize the range of ways that honor and shame touch on various aspects of life. For instance, wherever we speak of identity, we will soon run into matters that concern one’s honor or sense of shame. Identity involves belonging. And belonging entails any number of values that determine what we think worthy of praise or censure.

(In part one of the series, I considered the meaning of a “Christian Nation.”)

Christian Nationalism as Cultural Melting Pot

Accordingly, we begin by highlighting a point often overlooked by many people. In Taking America Back for God: Christian Nationalism in the United States, scholars Andrew Whitehead and Samuel Perry painstakingly detail why Christian nationalism consists of an amalgamation of subcultures. They argue that Christian nationalism is

“a cultural framework—a collection of myths, traditions, symbols, narratives, and value systems—that idealizes and advocates a fusion of [a particular sort of] Christianity with American civic life.” (10)

Contrary to the impression of some, “evangelicalism is not synonymous with Christian nationalism” (58). It is as much political and ethnic in its orientation as it is religious.

As they and others have observed, Christian nationalism

“is more common in the South with a strong representation in the Midwest. It is stronger in rural areas and smaller towns, less common in bigger cities. There’s also a class and education distinction here, more common in the lower middle class and more common amongst the population that does not have a college degree.”

In addition, while Christian nationalism is not a “white” phenomenon, the relationship between Christian nationalism and white Christians is noteworthy. Paul Miller says,

Christian nationalism would not claim that whites are inherently superior on the surface level. If you dig a bit deeper, you’ll find that Christian nationalists and white nationalists, agree on a range of subjects.

For example, if you ask whether racial inequality in America is primarily due to individual merit or due to structural systemic factors, Christian nationalists and white nationalists would agree it’s due mostly to individual merit. They would both advocate for strong immigration restrictions. They would reject that systemic racism exists.

There is a difference, but there is some overlap in those underlying attitudes.

What results? Whitehead and Perry explain how Christian nationalism “co-opts Christian language and iconography in order to cloak particular political or social ends in moral and religious symbolism” (153).

When It’s Us Versus Them

Christian nationalism forges rigid categories of “us” versus “them.” Whenever that happens, layers of underlying values dominate the group, reinforcing a particular honor-shame lens that affects everything else.

Consider, for example, the degree to which Christian nationalism and Southern culture conflate. In the American South, a perceived attack on one’s honor must be met with retaliation of some sort, otherwise, the person is seen as weak and loses far greater honor. Such inclinations fuel a cycle of responses that grow ever-increasing in intensity. Southern road rage serves as an apt illustration, where cutting someone off in traffic could quickly escalate to the offended driver pulling a gun on the other person.

Conflating Southern and Sacred Honor

How might this translate over into Christian nationalism? The Bible becomes a tool to justify such retaliatory instincts. God is a God of righteousness. He shows wrath to the wrongdoer. He conquers wicked invaders. Naturally, the Christian nationalist surmises, we should “fight back.”

One pastor of a “Patriot Church” sees the church engaged in a culture war. In response to Biden and the Democratic Party, he says,

“When you’re dealing with bullies, you have to fight back,” he says. He justifies this approach by saying, “The left doesn’t love the country at its roots… Freedom is the way, not the value system of the left, which is totally anti-Bible. But the Bible is the answer, and Jesus is the answer.”

This mentality is more Southern in origin than biblical. Christian nationalists are thus inclined (than non-nationalistic Christians) to embrace a far more adversarial and aggressive posture towards “others” whom they don’t regard as “patriots.”

No wonder Tony Perkins, president of the Family Research Council, responded as he did when asked, “What happened to turning the other cheek?” He replied, “You know, you only have two cheeks… Look, Christianity is not all about being a welcome mat which people can just stomp their feet on.”

No wonder Tony Perkins, president of the Family Research Council, responded as he did when asked, “What happened to turning the other cheek?” He replied, “You know, you only have two cheeks… Look, Christianity is not all about being a welcome mat which people can just stomp their feet on.”

In short, Christian nationalism distorts and misappropriates biblical texts and values in the interest of preserving an alternative set of honor-shame values.

I have given just one example. Others could be added, including the near idolizing of hierarchy. How quickly do people forget that the kingdom of God is not a democracy? Why do some act as if God gave Americans the Constitution to function in the same way the covenant he established with ancient Israel?

Christian Nationalism as Folk Religion

As Geoff Holsclaw aptly put it, Christian nationalism is folk religion.

A folk religion doesn’t have a defined set of belief, practices, or leaders.

It just has ad hoc set of beliefs, loose patterns of practice, and informal leadership who can change, shape, manipulate, and control the flow of power (energy or force) within the spiritual realm (the middle level) …

[Its] leaders (even if outcasts of sorts) know what is “really going on” in a world, and will tell you the proper remedy for your ills.

In essence, folk religions aren’t interested in logical consistency or the coherence of belief. They are focused on pragmatic results! The main focus of a folk religion is POWER.

Where folk religion grows, power trumps truth. Holsclaw direct our attention to the Jericho March that shortly preceded the assault on the Capitol on January 6th. He says,

The blowing of shofars, waving of banners, raising of crosses, and offering of prayers “invoking” Jesus’ name in these “sacred” places is a mashup of authentic Christian symbols and practice dropped into a context and purpose foreign to Christianity (the advancement of purely political goals wrapped in spirituality).

Why bring up folk religion? By definition, folk religions are a hybrid of a formal religion with a surrounding subculture. The blending can then create a grotesque distortion of what previously existed. What was shameful becomes honored. What was honored now is looked at as shameful.

For a superb podcast on this subject, check out Phil Vischer’s Holy Post episode “Christian Nationalism & the Good Life with Derwin Gray.”

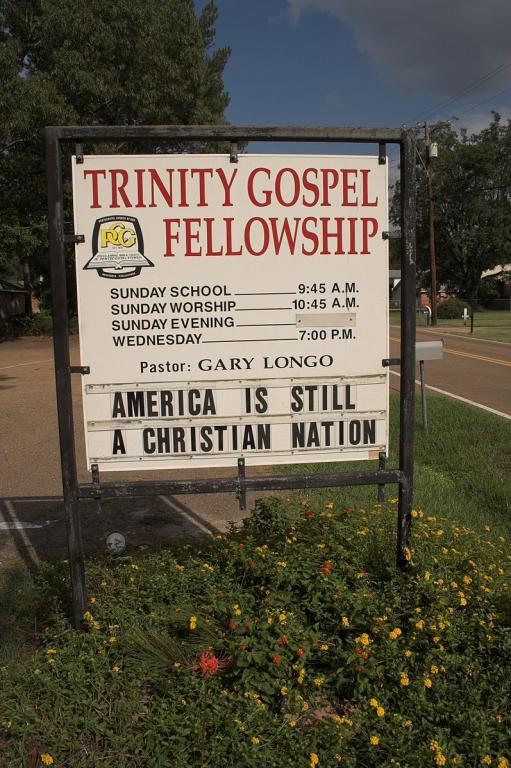

Photo Credit: Flickr/Derrek_B (Sign in Jackson, Mississippi for “Trinity Gospel Fellowship”)