Today’s guest post by Werner Mischke is an excerpt from his new book One New Humanity: Glory, Violence, and the Gospel of Peace (WCP, 2025), 206–08. It’s available at MissionBooks.org, Amazon.com, and other major retailers. Check out the book website, which includes short videos for each chapter.

Note: In Appendix 1, I contributed an exegetical article, “Reconciling Atonement in Ephesians 2: An exegetical approach.” This 10,000-word theological article examines the often-overlooked text of Ephesians 2:11-22 relative to the doctrine of atonement.

Depolarizing the Disciples

Consider also Jesus’s twelve disciples. Jesus calls Simon (later named Peter) and Andrew (Mark 1:16-20). Socially, they are Jewish peasants. From their earnings as fishermen, we imagine they would grudgingly pay taxes to Rome. Not only because they need every penny to support their families, but because their land and people are forced to exist under pagan Roman rule.

Then there is Levi (or Matthew), a tax collector. Jesus calls him, too, to join his band of disciples (Matt 9:9-10). Matthew collects taxes from his own Jewish community to support the Roman state. To faithful Jews, Matthew is a traitor. Luke tells us that Matthew made for Jesus “a great feast in his home, and there was a large company of tax collectors and others reclining at table with them” (Luke 5:29). Matthew was wealthy, upper class. We wonder: how surprised, how offended, were Simon and Andrew when they learned Jesus chose a traitor, a hated tax collector, to join their in-group?

At the other end of the spectrum is Simon the Zealot.[1] The name “Zealot” could have meant he was a member of an underground resistance group fighting for independence from Rome (i.e., a man of violence). If so, it is possible that Simon the Zealot might have wanted to kill Matthew the tax collector for Matthew’s complicity with unclean idolatrous Rome. Al Tizon comments, “No one dared to bring together fishermen, whom the state heavily taxed, and Matthew, who collected those taxes on behalf of the state. And to add fuel to the fire, Jesus invited Simon the Zealot, someone bent on overthrowing the Roman state, to join the group.”[2]

Finally, we add faithful women to Jesus’s group, likely of various social classes. These women provided for Jesus and the disciples “out of their means” (Luke 8:1-3). Women supporting Jesus and his (male) disciples? It’s a shocking inversion of traditional gender roles.

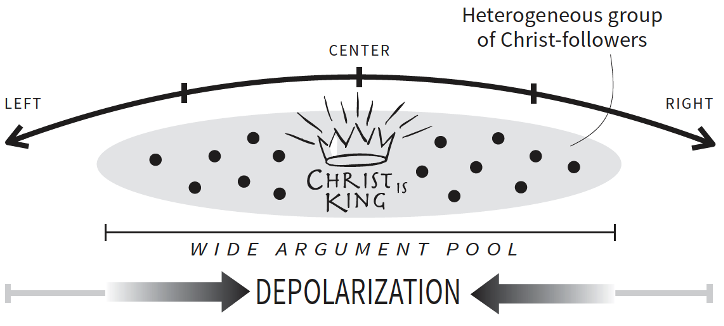

Luke is hinting at the subversive nature of Jesus’s unusual community. What matters is this: Jesus holds the group together. Jesus himself depolarizes and unites diverse persons and perspectives among his followers, as figure 12.8 below illustrates. Allegiance to Christ as sovereign Lord and truest human being relativizes lesser loyalties, lesser allegiances, lesser glories.

So, although group identity is often a potent source of polarization, when our identity is primarily in King Jesus, he is the depolarizing source of our unity in diversity. “Identity can be used to divide, but it can and has also been used to integrate.”[3]

This begs the question: To what degree does your local church offer this asset—the ministry of depolarization—to the world? Is this not an under-leveraged ministry of the church of our Lord Jesus Christ? Is this diversity-loving Jesus an outlier, a “woke” part of God, who happens to be a lot nicer than some bigger, truer, holier God? I jest. Obviously not.

This is Jesus revealing the true God. Jesus said, “I and the Father are one” (John 10:30). “Whoever has seen me has seen the Father” (John 14:9). God really is like Jesus, who loves, forgives, and transforms human enemies. Jesus brings persons and peoples together across social boundaries. “He is the radiance of the glory of God and the exact imprint of his nature” (Heb 1:3).

Depolarization in Ephesians 2

We see this same Jesus-centered reconciliation and depolarization in Ephesians 2:11–22. When Paul writes to the early Christian communities in and around Ephesus, he is advocating for local churches to embody the “one new man” (Gk., anthrōpos, humanity).

Paul is the former super-zealous Pharisee (Phil 3:5–6); in his prior life he was committed to separation from all-things-gentile. Now Paul is a slave of Christ and apostle to the Gentiles. He zealously advocates for a reconciled Jew-and-gentile assembly (Gal 2:11–14; Eph 2:11–22), a fellowship of peoples previously in conflict for centuries. This miracle of peace happens only one Way—through mutual allegiance to Christ the King whose body was crucified, and whose blood was shed to break down “the dividing wall of hostility” (Eph 2:13–16).

Why am I emphasizing this aspect of Christ?

The HUP [Homogenous Unit Principle] has silently and broadly shaped the American evangelical community. “It was a missional principle, and when it came to the US, it became a marketing principle: how to gather more people like us … mission morphed into marketing.”[4] For too long evangelicals have settled for homogenous units as a standard framework for gaining converts, starting churches, sustaining churches, and building community.

But in our increasingly diverse cities, many workplaces, the military, and other communities, this doesn’t look like Jesus. And the world knows it. “Whereas the world recognizes that segregation is a kind of moral failure, in the evangelical church it is basically a go-to strategy. Instead of seeking to be unified in our diversity, we segregate into communities that look alike, make similar amounts of money, appreciate the same kinds of music, and share the same social status.”[5]

In our broken world of social divisions and polarization, of violence and political tribalism, bullying, and unprecedented demographic shifts, of wars born of imperial or tribal jealousies, of social media shouting matches, of mass migrations and 100 million forcibly displaced persons[6]—what does it mean to follow Jesus?

[1] Matt 10:4; Luke 6:15; Mark 3:18; Acts 1:18.

[2] Tizon, Christ Among the Classes, 17.

[3] Fukuyama, Identity, Kindle loc 2552.

[4] Quote from Fuller Seminary professor Eddie Gibbs in Bishop, The Big Sort, 181.

[5] Goggin and Strobel, The Way of the Dragon or the Way of the Lamb, 203.

[6] UNHCR, “More than 100 Million People Are Forcibly Displaced.”