In discussing the recent scandal out of Notre Dame’s theology department, a question arose: Would it be possible for Joel Baden and Candida Moss to have argued well against the Catholic position on IVF? That is, is there another way they could have challenged the Catholic position that would have shown them worthy opponents?

I think there is, and I’m going to walk you through my thoughts on that. Before we begin, let’s go over some preliminaries:

1. I don’t for a moment question any aspect of the Catholic faith. This is an exercise in debate. It’s hypothetical. IVF is evil. Done.

2. Sheesh I’ve seen an awful lot of juvenile remarks on this topic. Don’t go there.

3. Here’s your required reading if you want to make sense of what follows, but you are joining this discussion late in the game:

- The original article posted at Slate. That’s what we’ll be correcting.

- My fisk of that article, so you can see the egregious problems it contained, as well as its strengths.

- My discussion of what makes for effective debate or earnest dissent.

- Mine or some other good tutorial on the ethical principles of double effect and ends vs. means.

4. You did all that? Okay good. Let’s go.

***

The Argument Against Bad HR

Baden and Moss present a fair bit of evidence that Emily Herx was treated shabbily by her employer, a Catholic school. Since I’m not familiar with the details of the case, and very few of us are, we’ll work on the assumption that the evidence they presented was sound. We are going to assume that they have verified their facts, and that they aren’t indulging in gossip.

Naturally there’s another side to the story, and a subsequent discussion would require them to respond to whatever that other side might be. But for the moment, they’ve brought back to the surface a very important issue in Catholic education. Well done.

The Argument for a Catholic-Model IVF

This is where the story gets interesting. The usual discussion about IVF doesn’t go very deep, because the simple fact that the procedure involves killing innocent human beings makes it a no-go. In Emily Herx’s case, Baden and Moss observe, the Herx family was committed to using all the embryos created via IVF. Therefore, the killing of innocent human life was no longer a problem.

Well done. But the argument can’t rest there, because Baden and Moss have not yet answered the other objections to IVF. In debate (and earnest dissent), one must, in some manner or another, respond to the opponent’s assertions. So if the authors had wanted to engage in proper debate, what would they tackle next?

1. They’d have to indicate that the Herx family was using Mrs. Herx’s egg and Mr. Herx’s sperm. The article is silent on that point. Every child has a fundamental right to know and be reared by his mother and father. While terrible circumstances often prevent that from happening, it is immoral to intentionally create a situation in which a child is deprived of that right.

In theory they could, alternately, argue that children have no such right. I don’t think they would have an easy time mounting such an argument.

2A. They’d have to demonstrate that Catholic moral theology errs in requiring that every act of procreation be the result of a normally-completed sexual act between husband and wife. This is the final objection to IVF. The Church actively approves and supports fertility treatments that are geared towards assisting couples in conceiving via marital intercourse. It only opposes those treatments which remove procreation from the union of man and wife, or that have some other immoral aspect to them (killing or orphaning children, for example).

This would be a tall order, and I don’t know along what lines they might make such an argument. An important nuance to watch for would be the dual grounding of Catholic thought both in natural law and in our understanding of marriage as a sign pointing towards God’s relationship with mankind.

[As I mentioned above, I stand with the Church absolutely on this point.]

2B. Alternately, they could argue that fertility treatments that separate procreation from the marital act, but that are otherwise unobjectionable, might be tolerated in non-Catholic employees who aren’t entrusted with teaching the Catholic faith. They might build their case by offering evidence that Catholic dioceses regularly employ non-Catholics in staff-type positions, and do not consider the use of contraception, a similar situation, to be a cause for termination. Or they could simply argue that prudential judgement permits non-Catholic employees some level of discretion in their day-to-day moral lives outside of the classroom.

This latter approach wouldn’t clear the way for Catholic staff to use IVF. I don’t know whether Mrs. Herx is herself Catholic or not. Their choice of argument might be guided by the answer to that question.

Could They Skip the IVF Question Altogether?

What if Baden and Moss didn’t want to question the morality of IVF? Perhaps they realize it’s a losing battle to do so, or that it falls outside their field of competence. Would they still have something to write about if they set aside the issue of IVF?

Certainly. Rather than using false evidence to support their (erroneous) thesis that the Catholic Church condemns infertile women, they could have:

1. Discussed the genuine hardship that infertility creates, and suggested ways the Church could provide more support to employees in such straits.

2. Offered evidence of genuine instances of thoughtlessness towards childless couples on the part of some Catholics, which has been widely reported in the Catholic corner of the internet, but would perhaps be worth sharing with readers of Slate. Since Moss teaches in the theology department at a Catholic university, she’d be in a prime position to demonstrate that this attitude was contrary to the Catholic faith, in addition to being unworthy of anybody.

Either of these approaches would have conceded that the school did (likely) have grounds for termination, though it could still be shown that the situation was handled unfairly. An area on which I’m not equipped to comment, but that Baden and Moss might have chosen to investigate, is the intricacies of the legal conflict between the protection of persons with disabilities and the constitutional right to free exercise of religion.

Why Bother Rewriting a Lousy Op-Ed?

I don’t have a particular reason for taking interest in this case over all others like it, other than that it happened to land on my desk. But I write on this because the Slate article is a symptom of something much bigger: We’ve utterly lost our ability to argue.

I can remember back in freshman accounting being given one of those “thinking exercises” in which three options for how to handle a transaction were proposed, and you had to make an argument for the proposal assigned to your group. As it happened, my group was assigned an option that was clearly the wrong solution. One of the other proposals was obviously the right way to handle the problem in question. But no matter, an assignment’s an assignment. I mounted my case . . . and convinced the professor.

I was horrified.

I knew then that our culture had gone terribly, dreadfully wrong. That we had lost the ability to think rationally.

Don’t be part of that. When you argue, argue in the pursuit of the truth.

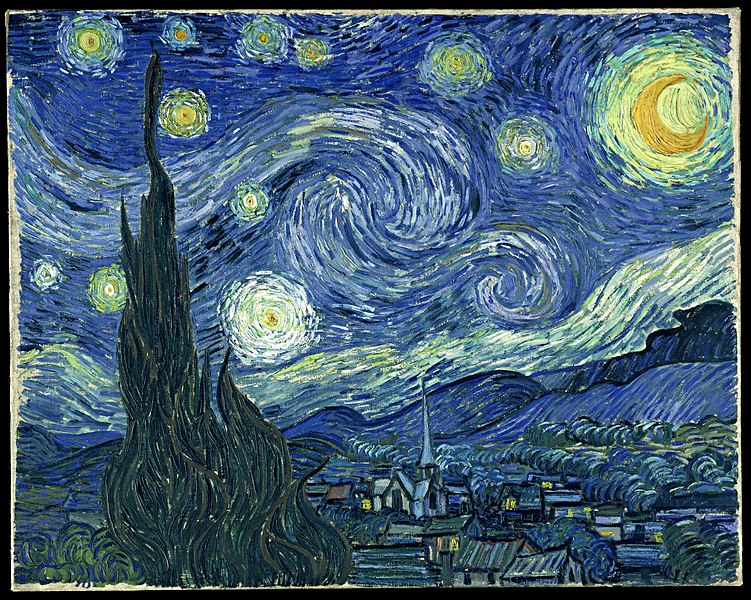

Image by Vincent van Gogh [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons