You know the story: America’s mighty mainline Protestant churches once stretched from sea to shining sea, embracing the vast majority of American people who worshiped week after week, filling glorious churches with their hymns of praise. But, alas, they are now reduced to a handful of aging folks who can scarcely pay to keep the church furnace running. In a few weeks they’ll all be gone.

Martin Marty has written that the story of “mainline decline” is so hackneyed by now that we should just reduce it to one word—mainlinedecline. It is a narrative that has dominated the interpretation of church life in America’s older Protestant denominations since 1972, when Dean M. Kelley wroteWhy Conservative Churches Are Growing.

But it may have a seriously faulty presupposition. We need to ask just how mighty were the older, non-Catholic and non-Orthodox Christian churches in the early 20th century. Kelley’s statistics for earlier periods were based on Edwin Scott Gaustad’s Historical Atlas of Religion in America. Kelley used these figures to show that the older Protestant churches had grown proportionately with the U.S. population up to 1960. His statistics for the period 1960–1970, in which he saw the beginnings of a decline in membership in what he called “ecumenical” churches, were based on the Yearbook(s) of American Churches prepared by the National Council of Churches, where he served.

Kelley’s perception of the beginnings of decline in oldline church membership was undoubtedly on target. Although his conclusions were met with consternation when they came out, few scholars have had their earlier scholarly work as vindicated as Kelley did.

But even if Kelley’s statistics about decline in oldline church membership have proven true, many questions remain about the presupposition that the “ecumenical” or “mainline” Protestant churches were once—perhaps early in the 20th century—the very heart of American religion….

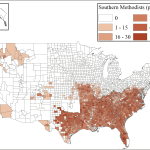

The Association of Religion Data Archives, based at the University of Pennsylvania, offers statistics on most U.S. denominational groups going back to 1925. These membership statistics paint a very different picture of American denominational life than the one often presumed in the standard narrative of decline, for they call into question Kelley’s claim that the oldline denominations grew proportionally with the U.S. population through the 1950s or 1960s….

So how did these churches come to be considered the mighty American mainline if they did not statistically represent anything close to a majority of Americans? That seems to be a complicated story that involves at least the following elements.

- The distant memory of a time—prior to the Civil War—when Methodists, Baptists, Lutherans, Episcopalians, Congregationalists, and Presbyterians probably did constitute a majority of non-Catholic Americans, if not of Americans as a whole.

- The corresponding cultural impression that these churches were the true American churches in contrast with other Christian (Catholic and Orthodox) and Jewish groups that were still associated with immigrant communities of the early 20th century.

- The engagement of these churches in the Federal Council of Churches, the predecessor of the NCC, which was empowered by the U.S. government to allocate religious broadcasting slots for radio and television.

It’s not surprising that the term mainline would become a favored way to describe these churches, evoking the wealth and privilege of the affluent suburbs of Philadelphia that were clustered along the “main line” of railways leading west from the city.