Perhaps you were taught what I was taught. There is such a process called microevolution but there is no such process called macroevolution. That is, within a species there is variation and change but there is no evolution of one species to another. I learned this — or something like it.

Perhaps you were taught what I was taught. There is such a process called microevolution but there is no such process called macroevolution. That is, within a species there is variation and change but there is no evolution of one species to another. I learned this — or something like it.

A threshold issue in evolutionary theory is speciation. That is, that one species can evolve into a new species. What then is a species? Denis Alexander, in his wonderful book Creation or Evolution: Do We Have to Choose?, examines speciation at length and seeks to demonstrate these three points:

First, speciation definitely happens. Second, in some cases it can be observed occurring in the wild during the lifetime of a single biological investigator. Third, there are different mechanisms that account for speciation, not just one mechanism (113).

He looks at allopatric mechanisms (when a species gets split two or more geographical locations), sympatic mechanisms (splits without geographic changes), and polyploidy (chromosomal multiplication). He looks at plants, where 50% of flowering plant species are the result of this mechanism. He looks at mosquitos, cichlid fishes, ring species of gulls, salamanders… but he’s got enough here to convince of speciation at various levels. It’s convincing to me, at least.

It should be clear by now that there is nothing particularly special about speciation from a scientific point of view and as our understanding of genomics increases, so the distinction between micro- and macroevolution begins to look less useful (121). [He doesn’t think the terms are in the end of help.]

One of the most stimulating areas of science is the diversity and number of species, and it ought to stimulate theological thinking too! Here is Alexander’s sketch:

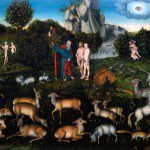

The number already classified is around 1.5 million (excluding prokaryotes, single-celled organisms like bacteria). According to the 2013 Catalogue of Life index, there are already described some 4,835 mammalian species, about 10,000 species of birds, around 32,000 fish species, 250,000 plants and 46,000 species of fungi. Yet all of these numbers fade into insignificance compared to the 860,000 insect species named so far, of which 200,000 are beetles. It has been estimated that 85-90% of species, both terrestrial and aquatic, have still to be named and classified, so the final tally of species in the world could be nearer 10 million than 2 million, especially if the proportion of cryptic species turns out to be as high as some people think. Adam was commanded by God in Genesis 2:19-20 to name all the animals, but we have a long way to go in finally fulfilling that command! (123).

Now one more stunning:

More than 99% of all the species that have ever lived on this planet are now extinct (124).

Finally, Alexander takes a look at the fossil record for what it says about evolutionary theory:

Many people think that there are still missing links in the map of life, but that depends on what they mean. To the question: ‘Do we have a complete map of the whole “city” of evolution, showing in detail how every single road (= species in this analogy) came into being and is connected with every other road?’, then the answer is ‘No.’ We don’t even have a complete catalogue of all the road names, let alone know how they all interconnect to form the complete city.’ But if the question is the more manageable one: ‘Do we have some detailed maps of quite a few areas of the “city” with a good idea as to how the main areas join up?’ then the answer s definitely ‘Yes’ (149).

He dips into the history of the evolution from fish to tetrapods: Eusthenopteron to Panderichthys to Tiktaalik to Acanthostega to Ichthyostega.

Alexander’s final analogy in conclusion:

If we translate the bush of life into the metaphor of a giant jigsaw puzzle, laid out across the nearest football pitch (for example), then what we see are huge swathes of puzzle well joined together, but we also see other areas (like the pieces representing the Ediacaran fauna) still lying separated, without enough data to join the pieces up properly. But of course evolutionary biologists are delighted by the bits not yet resolved. Not only do they represent a fascinating challenge, but they also keep them happily employed with a job yet to do! (152-153)