If anything is said of women in the patristic era it is often that they were non-influential, non-writing, non-speaking, and the like. In other words, if you want to learn about women in the church the best place is not the patristics.

If anything is said of women in the patristic era it is often that they were non-influential, non-writing, non-speaking, and the like. In other words, if you want to learn about women in the church the best place is not the patristics.

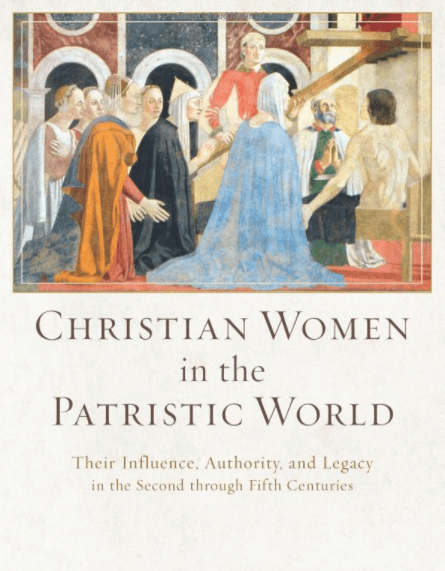

In their new book, Christian Women in the Patristic World: Their Influence, Authority, and Legacy in the Second through the Fifth Centuries, Lynn Cohick and Amy Brown Hughes challenge the common view of women in this era.

In fact, their study unveils some perceptible shifts in what we can find:

Our study reveals men and women thinking together about the nature of the Christian church and its teachings. The women considered in our book captured the imagination of average Christian pilgrims, learned male authors, and government officials. Indeed, some of the women we discuss exercised authority in the imperial government, wrote influential prose and poetry, and traveled on pilgrimage and established basilicas and martyr shrines and relics. This book celebrates their legacy.

Here is an important observation and it is one that needs to haunt how we talk about the patristics. Was it just the Creeds and the Councils and the theologians fighting it out?

For example, this historical period saw the establishment of creeds and doctrines as church councils, made up of male clerics and scholars, defined Christian doctrine. But this is only part of what happened—and if this half is told as though it is the entire story, a false impression is created that women were ancillary to the development of the church’s doctrines and practices. As our study shows, however, women made numerous contributions to theological discussions and religious practices.

There is a both-and approach in Cohick and Hughes, a both critical and a charitable reading of the patristics. See the good and name the bad.

Our approach stands over against both those works of modern scholarship that simply lament and dismiss the church fathers as hopelessly misogynistic, as well as those that take a naive, pious perspective on the evidence, for both approaches fail to deal analytically with the sources. Within these early Christian writings, we find disparaging comments about women or the female sex as well as active engagement and genuine conversation with learned women. We do not read the church fathers’ statements about women as direct windows into church doctrine and practice; rather, we nuance these texts by considering the ways women themselves shaped their lives and their social worlds.

At the heart of their project is a candor about the realities of women in the patristic period:

Nevertheless, women often faced an uphill march in pursuing their goals. We examine the many obstacles (ideological, cultural, theological, and political) that prevented women, in general and within Christianity, from living their lives to the same full extent that was available for men of comparable rank and station.

And a claim:

The evidence shows that these women carried theological influence, as we will see with Gregory of Nyssa’s remembrance of his sister Macrina as an authority on christological imitation and on the nature of the resurrection (chap. 7) and with Melania the Elder’s involvement with the Origenist controversy, a wide-ranging debate on the reception of some of the more speculative teachings of Origen, including the nature of the resurrected body and the preexistence of souls (see chap. 8).

Feminism has its voice in this book, and here’s why:

Feminists have shone the spotlight on history and literature, demonstrating how the oppression of women is deeply entrenched, systemically permeating political structures, domestic life, and religious devotion. Of course, Christianity is not immune to the charge of denigrating women and in fact has often been the appropriated force behind the subjugation of women and even the instigator of atrocities against various groups of women. Because of this oppressive norm, feminists read texts with a hermeneutics of suspicion, assuming that the author is reflecting a patriarchal bias. Yet even in the most oppressive of societies and situations, we have examples of women living their lives with creative energy and mobility, taking opportunities as they arise, owning agency and demonstrating religious conviction in ways that surprise modern sensibilities, and contributing to the variegated story of early Christianity.

To find the women and their place in the patristic era requires patience and skill:

We do not have nearly enough of these accounts, but what we do find is that Christian women often had to navigate the tricky congress between their femaleness and the faith, tradition, and Scriptures that they held so dear.

Cohick and Hughes advocate for “responsible remembrance.” One of my favorite themes in this book is this very idea:

In this book we will be looking at women of various regions, backgrounds, situations, and temperaments from the earliest centuries of Christianity and remembering the many ways they assumed authority, exercised power, and shaped not only their legacy but also the legacy of Christianity. This remembrance is self-aware. Perhaps controversially, this remembrance is not a neutral reading; rather, this reading is functionally an “admission of advocacy,” a speaking for the participation of the other, those who have been relegated and silenced.10 For our sake and for the sake of others, we need to commit to advocacy and practice what Justo Gonzalez calls “responsible remembrance.”

Hence, Cohick and Hughes are advocates, not simply historians. They want to know what we can find out about women and what they were doing, and responsible remembrance is not naive and it must be critical and name what needs to be named:

Part of the role for advocates for early Christian women is to bear the responsibility to critique the patriarchal norm and the vitriolic language used by some of the church fathers, such as Tertullian. And the responsibility extends to considering positive views of women found in these texts as well.

As a result, we might be put off by how these biblical women are portrayed by the church fathers. Our reading should be one of advocacy for a more inclusive gender framework in reading the biblical text; yet our reading of these ancient interpreters should also be marked by charity. We must take into account that a writer cannot excuse himself from his context and the information available at the time. But this charity does not mean we excuse the author’s silencing or oppression of women because “that’s just how it was back then.”

But women played a far more important role than is accepted and this comes through when one sees that “theology” is more than writing long philosophical treatises. Theology is, as Kavin Rowe has written, a way of life. How so?

A fundamental presupposition of this project is that women were instrumental in the construction of Christian identity and theology in the first five centuries of Christian history.

Fundamental to our approach is the supposition that theology in the early church was a dynamic and organic project that included a myriad of voices and approaches. It is a significant error to limit constructive theological work to councils and specific kinds of texts because, as will become clear especially in regard to the central discussions of the Trinity and Christology in early Christianity, core work on these subjects was happening in imaginative rewritings of Plato, the construction of the Christian historical narrative, letters between friends, dialogues in the middle of the night, the establishing of monastic communities in homes and in the desert, pilgrimages to the Holy Land, the reception of the martyr tradition, and the ascetic negotiation with the body.

What Cohick and Hughes advocate then is for a “prismatic paradigm” to theology!

In this prismatic paradigm for interpreting early Christian theology, women’s theologizing is fundamental to the development of Christian thought and should not be relegated to the fringe or regarded as a concession prize at best.