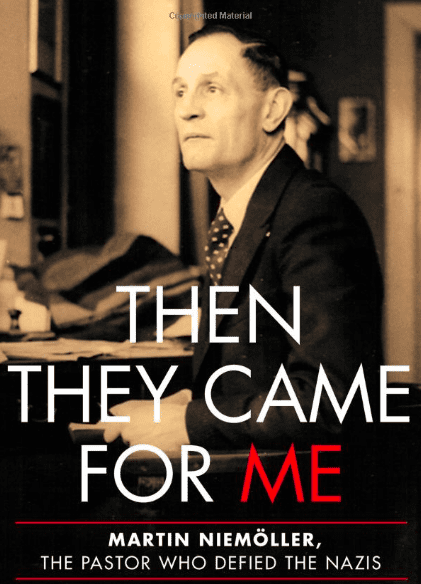

Martin Niemöller has been covered up by the heroic story of Dietrich Bonhoeffer even though for more than a decade after WW2 Americans saw Niemöller as the hero. His story has been told by Matthew Hockenos in Then They Came For Me.

Martin Niemöller has been covered up by the heroic story of Dietrich Bonhoeffer even though for more than a decade after WW2 Americans saw Niemöller as the hero. His story has been told by Matthew Hockenos in Then They Came For Me.

This is unswervingly honest story about a man who was far from perfect but who grew to have his heart in the right place. This is not a hagiography but a straight shooting story by a noble historian. Some have laundered Niemöller’s story; not so Hockenos.

While I have known of Niemöller for years, even decades, I’ve not read anything about him this extensively and this book brings out the stories of his wife, Else, and the children and the suffering the family went through in WW2 and after. What I perhaps most liked about this book was opening up the realities of German pastors and the German church situation after the war. What most seemed to be doing was covering up their own complicity, and this may be where Niemöller was most heroic: he admitted complicity and called German pastors, German churches, and Germans to confess their guilt.

Niemöller’s story is not pure: he was drawn into pastoring after a military career in WW1 (a proud U boat officer); he was a German nationalist; he was bitter about the Versailles Treaty’s treatment of Germans; as a pastor he supported the National Socialists though never officially joined the Nazi Party; he voted for Hitler two times; he originally did not defend Jews as Jews but only Jewish Christians; he eventually exaggerated dimensions of his and the church’s opposition to Hitler; he only slowly saw his own anti-Semitism.

Yet, following his military service he became a pastor with unusual passion; he defied Hitler’s crossing the line between church and state; he defied the “German Christian” movement with its blending of church and state in blasphemous ways; he was arrested by Hitler for opposing Hitler’s imposition in the church; he was released from prison only to become Hitler’s personal prisoner — in Sachsenhausen and then Dachau; he was imprisoned most of a decade.

Throughout his struggle in Germany he was mostly aligned with Karl Barth, and this snippet from many years later illustrates the activist, passionate approach of Niemöller over against the sophisticated, activist, intellectual approach of Barth:

The two enjoyed kidding each other, especially over their respective approaches to theology. Barth once told a mutual friend that Niemöller should put his theology on a boat, sail it out to sea, and sink it. Niemöller gave as good as he got, telling a biographer, “I have never cherished theologians. Take Karl Barth, my dearest friend. All his volumes are standing there. I have never read any of them. I never heard a lecture by him. Theologians are here only to make incomprehensible what a child can understand.” At Niemöller’s sixtieth birthday celebration, after decades of friendship despite periods of great strife between them, Barth joked:

Not so long ago, a conversation between Martin Niemöller and myself went like this. “Martin, I’m surprised that you almost always get the point despite the little systematic theology that you’ve done!” “Karl, I’m surprised that you almost always get the point despite the great deal of systematic theology that you’ve done!”

The Confessing Church was run by Niemöller but its theology was Barth’s.

The tension between Hitler’s German Christians and the Confessing Church (and not all here were alike, as some were much more amenable to Hitler than others), and this story expresses that tension:

The parish of Schöneberg in central Berlin was the site of one such duel. One Sunday a conflict arose between opposing pastors and their flocks over which group had the right to use the church. Both sides claimed possession by occupying strategic areas of the building. The German Christian pastor, Gerhard Peters, stood in front of the altar as his supporters arrayed themselves in the front pews. The opposition pastor, Eitel-Friedrich von Rabenau, held the pulpit while his followers piled into the rear pews. From the loft, a trombone choir accompanied opposition parishioners singing Advent hymns; from the same location, with gusto, the organist accompanied the German Christians singing “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God.” When the musical confrontation died down, Rabenau tried to preach from the pulpit, while Peters recited the liturgy from the altar. Cries of “We want to hear Rabenau’s sermon!” and ‘Peters is abusing the word of God!” were heard. The row lasted two long hours, with parishioners nearly coming to blows. Eventually Rabenau conceded the church to the German Christians and left the building with his following (91).

While in prison he became an American Christian pet project and America’s saw him as a personal agenda — get him released and he will become the heroic model of the Christian persecuted under Hitler.

But upon release from prison at the end of WW2 it was obvious Niemöller remained a German nationalist, and the stories of the heroic Niemöller were dealt a deep blow.

Insisting that most Germans were ignorant of the scale of Nazi atrocities and shocked by what they saw when the Allies liberated the concentration and extermination camps, he asserted, “You are mistaken if you think any honest person in Germany will feel personally responsible for things like Dachau, Belsen, and Buchenwald. He will feel only misled into believing in a regime that was led by criminals and murderers.”

He came to America under opposition as the first German to be given a visa — he spent the time defending himself, defending the suffering of the German people who were being oppressed by American denazification policies, and he raised lots of money for suffering Germans. But he never convinced many of his integrity; he was always a big question mark for many.

But Niemöller’s story is the story of a man who changed his mind and nothing is clearer in Hockenos’ wonderful book: over and over he took a passionate view, experienced opposition, and slowly changed his mind. His first instincts to major situations were too nationalistic, too German, too undemocratic, and too unChristian. Yet, the man changed his mind over and over.

He was the first to speak publicly from the German pastoral community in terms and tones of confession; that the German people bore guilt; that the pastors did not speak against Hitler enough or clearly enough or often enough.

While fighting denazification he started to open his mind on demilitarization of Germany (which cut against the grain of Germany’s renewed fears of Stalinist Russia); he saw good in the churches of Russia; he began to fight for peace in Gandhian terms; he gradually became a pacifist; and he eventually became a thorough-going progressive for peace in all categories. Yet, he was blind to dimensions of racism, like white privilege, and yet grew and worked against his prejudices.

Some people, not that many and Bonhoeffer was one, have clarity of mind into deep socio-political and theologically-informed issues — like Nazis, like war, like racism, like militarization — early and stay the course. Far more are like Niemöller who have to learn and grow and change their mind. Speaking of Bonhoeffer, how about this little-known fact?

When Niemöller wasn’t writing letters, worrying about church business, or preparing his defense for the upcoming trial, he took advantage of solitary confinement to read books, many in English, including Thomas Macaulay’s multivolume History of England. He twice waded through the New Testament in Greek, perhaps reviving fond memories of his gymnasium days and reading Greek poetry for fun. He received a copy of Bonhoeffer s now-famous text Discipleship with an inscription from his colleague: “To Pastor Martin Niemöller at Advent 1937 in brotherly thanks. A book that he himself could have written better than the author.”

Niemöller’s life is a paradigm of socio-ethical sanctification. Any reading of this book will help pastors especially to become more patient with themselves and with others, and perhaps encourage them to tell their own stories honestly — stories of growth and changing course.

Though Niemöller may never have composed these lines himself he used most of them if not all of them. Hence, they are both his and attributed to him — and the evidence is not clear. They are, however, brilliant:

First they came for the Communists, and I did not speak out — because I was not a Communist.

Then they came for the Trade Unionists, and I did not speak out — because I was not a Trade Unionist.

Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out — because I was not a Jew.

Then they came for me — and there was no one left to speak for me.

When most think of Germany and WW2 and the church and the pastors, they think of Bonhoeffer. But for a decade or more after WW2, Niemöller was the story. It is time for his story to be more known to day.