In the final chapter of his book Early Christian Readings of Genesis One: Patristic Exegesis and Literal Interpretation Craig Allert returns to Basil and his discourses on the days of creation. He explains the title of the chapter (ON BEING like MOSES):

In the final chapter of his book Early Christian Readings of Genesis One: Patristic Exegesis and Literal Interpretation Craig Allert returns to Basil and his discourses on the days of creation. He explains the title of the chapter (ON BEING like MOSES):

The title of this final chapter may seem odd in light of the main topic of this book. Perhaps that is a signal of how far removed we are from ancient readings of the Bible that emphasize the theological and are not controlled by history. One would be very hard pressed to find in the earliest interpreters of sacred Scripture an approach that is intent only on finding direct one-to-one correspondence with strictly historical occurrences. Instead, one finds Scripture interpreted in a manner that emphasizes a call to a deeper spiritual life wherein the salvation of humankind and the ultimate goal of seeing God (contemplation) are overarching. Thus, in this final chapter I will explain how Basil uses Moses, the author of the creation narratives, as exemplar in that call. (p. 303)

Whether Basil thought the earth young or old, creation instantaneous or extend over a matter of days or more, is beside the point in his interpretation. He exhorts his hearers (and us his readers) to participate in the theology revealed in Genesis – to be like Moses in this regard.

The exhortation to participation is made even clearer in the opening remarks of Basil’s sixth homily on the Hexaemeron. There he compares the hearers of his homilies to the watchers of an athletic competition, and he encourages both to be more than mere observers. He invites his listeners to join with him in the “contemplation [theoria] of the wonders proposed” as a “fellow combatant,” rather than a “judge.” The distinction between Basil’s Christian rhetoric and the problems of classical rhetoric is also present here. The examination of the structure of the world and contemplation of the wonders proposed, he claims, is not from the wisdom of the world, but from Moses. God taught Moses “face to face – clearly, not in riddles.” Just as Moses trained his mind to meet God, so Basil’s hearers need to train their minds “for the consideration of what we propose.” (p. 306)

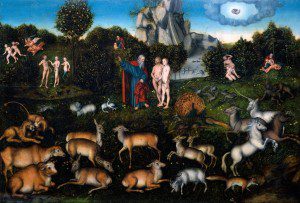

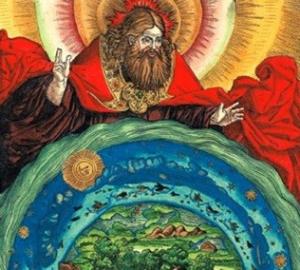

In two discourses that followed after the his Hexaemeron, Basil commented on the nature of humanity, upholding humankind’s dignity as the image of God. The image of God does not involve bodily shape or the flesh, as God has neither of these – despite the artist’s tendency to display God as a man (e.g. Cranach’s painting of creation shown to the right). Rather, image of God is connected to our “inner being” and ability to reason and rule. For Basil “the body is an instrument of the soul because the soul is the human being.” (p. 309) The ability to rule includes the ability to rule over the passions of the flesh – an ability renounced in the fall.

In two discourses that followed after the his Hexaemeron, Basil commented on the nature of humanity, upholding humankind’s dignity as the image of God. The image of God does not involve bodily shape or the flesh, as God has neither of these – despite the artist’s tendency to display God as a man (e.g. Cranach’s painting of creation shown to the right). Rather, image of God is connected to our “inner being” and ability to reason and rule. For Basil “the body is an instrument of the soul because the soul is the human being.” (p. 309) The ability to rule includes the ability to rule over the passions of the flesh – an ability renounced in the fall.

Basil also comments on the “likeness” of God. In Genesis 1:26 we read “Then God said, “Let us make mankind in our image, in our likeness, so that they may rule …” The likeness and image are two aspects of humanity. According to Allert:

Image and likeness are not the same thing. We have the image by our creation, but we “build” the likeness by free choice. Humanity is conformed to that which is according to the likeness of God by free choice – “the power exists in us but we bring it about by our activity.” The power is afforded to humanity because of its creation according to the image. In fact, the free choice humanity exercises in becoming like God is the Christian life: “For I have that which is according to the image in being a rational being, but I become according to the likeness in becoming Christian.”

… Thus, for Basil the deliberation in the Godhead to create humanity according to the image and likeness makes “the creation story … an education in human life.” The image is given, but the likeness is left incomplete so that humanity may complete it themselves. Yet the power of being created according to the image enables humanity to do so. This is precisely how Basil defines Christianity- “likeness to God as far as is possible for human nature.” (p. 310)

Basil is not concerned with the mechanics of creation, including the creation of human beings. He is focused on the theology of creation. This is the message that has the power to transform. Allert concludes the chapter (after several additional examples from Basil):

Basil is not concerned with the mechanics of creation, including the creation of human beings. He is focused on the theology of creation. This is the message that has the power to transform. Allert concludes the chapter (after several additional examples from Basil):

Basil’s primary interest is not in the events behind the text, and his understanding of the creation of humanity shows this. I have suggested that Basil is asking his listeners to be like Moses. This is synonymous with the restoration of humanity returning to paradise, which means a life “unenslaved to the passions of the flesh, free, intimate with God.”

Returning to paradise is the restoration and goal of the human life, and this is what the creation story ultimately shows. Consoling ourselves with material things keeps us from paradise. This is why the story of creation is “an education in human life” and why the story of creation should be read with an eye toward that end. The history behind the text does not concern Basil, but the theologia behind it does. (p. 324)

Allert’s walk through early Christian readings of Genesis 1 is fascinating, although he often simply presents the evidence and leaves it to the reader to connect the dots and draw a conclusion. In the process of wandering through their writings, Allert brings to light the concerns and commitments of the early church fathers. They did not read Genesis as modern literalists or as modern skeptics. Their concerns were shaped by their own context and by the questions raised in pagan Greek and Roman culture. The text was taken seriously, but it was always read with a Christ-centered focus and emphasis on the theological message and its ramifications for Christian life. They cannot be honestly appropriated to defend or refute modern young earth creationism. They simply did not have the questions or concerns that allow direct application to this particular modern point of contention.

Reading with the fathers enriches our Christian faith, but does not answer all our questions.

If you wish to contact me directly you may do so at rjs4mail [at] att.net.

If interested you can subscribe to a full text feed of my posts at Musings on Science and Theology.